Bridges are more than constructions – they have a character, and stories to tell. They can change lives, influence people and places. Their presence makes a massive difference. In this post, I want to draw out some of these implications. What is a bridge all about? What kind of life is lived on and around a bridge? What is it like to be a guardian of such a bridge? Bridges, yield your stories, please!

From England to Wales

‘I build bridges for a living,’ said the middle-aged man with a fancy car.

It was 1969, and he had just given my boyfriend and me a lift across the new River Severn road bridge, from England to Wales. Bridges were therefore very much a topic of conversation.

Really? I had never thought of bridge-building as a profession before. Perhaps he meant it metaphorically, working as a mediator? But no, apparently he was a practical bridge builder, a specialist engineer.

It was less than three years since the first Severn Crossing Bridge had been built. Indeed, it seemed something of a miracle when we sped over this vast expanse of river. Previously the same journey had either meant a very long drive round via Gloucester, or possibly taking the little foot passenger ferry boat running between Aust on the English side and Beachley in Wales. We were students, going as far as we could, as cheaply as we could – we ended up pitching our small tent in a wonderful bay on the Gower Peninsula.

Perhaps we were less sophisticated back then, but in more recent years I experienced a similar sense of the miraculous, when walking – or was it flying? – across the ravine on the new footbridge at Tintagel in Cornwall. The two sides of the cliff were connected by a land bridge in medieval times, but this collapsed centuries ago, and since then a steep scramble down and back up had been the only way to get across. But now, as one of the project managers says on this video: ‘It was just the most amazing moment, to be able to walk across that bridge and see a view that hasn’t been seen for five hundred years.’

The River Exe

One story I’ve researched is that of the bridge over the River Exe, in the city of Exeter. I chose it as my special project during my training as an Exeter City Red Coat Guide.

The River Exe starts as a trickle in boggy upland Exmoor, near Simonsbath, winding its way down to the sea at Exmouth some 63 miles further away. The city of Exeter is just a few miles from the coast, and both the river and the nearby ocean have always been crucial to its history. In Roman times the city was known as Isca Dumnoniorum, the former territory of the Celtic Dumnonii tribe; the Romans made good use of river and sea for valuable import/export trading, and based their port about five miles downriver at Topsham – which happens to be where I currently live.

What’s in a name?

You’ll see from the map that the River Exe joins up with the River Barle just below Dulverton. So why should we take it for granted that the Exe swallows the Barle, rather than the other way round? As the Barle is a beautiful and major river in its own right, quite frankly it could have gone either way with the naming of the river! In which case we might now be talking about the city of Barleter. Not to mention Barlford, Barlminster and Barlmouth.

Below: some bridges upriver on the Exe, as it meanders across Exmoor; the bridge on the right is at Winsford

The River Exe has charming wooden and stone bridges along its early lengths, but when it passes through Exeter itself, it has become broad, powerful, and often turbulent. Building a bridge here is fraught with difficulty. Flooding used to be common too, until modern flood relief schemes were implemented. So how might the Romans have managed, with travellers, animals and goods arriving at West bank of the new city? There were probably ferries, and there was certainly a ford, but this was often dangerous to cross, even on horseback. A bridge would have been a necessity.

Mark Corney, a specialist Romano-British archaeologist, told me that the Romans may well have built a bridge of stone or stone and timber across the river at Isca Dumnoniorum, similar to others which they built in Europe, but no traces of it now remain. We can assume that this was eventually washed away, and that wooden bridges were probably built in Saxon and early medieval times, which were themselves destroyed even more quickly.

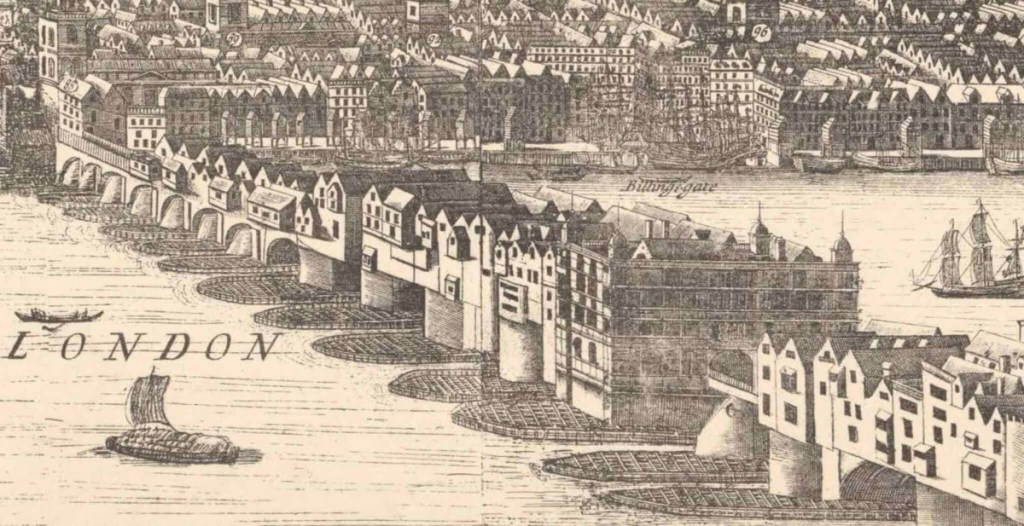

Building Exe Bridge

In about 1200, the first ‘modern’ stone bridge was built across the river, with some 17 or 18 arches. It was broad enough for the two-way traffic of horses, donkeys, cattle, carts, pedlars, and so on. And it was imposing, at around 282 meters long – about two thirds the length of the old London Bridge. This medieval bridge served the city until the late 18th century. Part of it remains today, and the intrepid visitor can still walk across it, surrounded by a swirl of traffic racing around the new road system on the periphery. The river itself has been gradually channelled into narrower boundaries, so much of the old Exe Bridge passes over low-lying, but dry ground.

Building Bridges as a Virtue

The building of stone bridges in Britain during that medieval period was loaded with significance. It was a mark of charity for wealthy merchants to contribute towards bridge-building – in Exeter, the Gervase family, father Nicholas and son Walter, dug deep into their well-stocked coffers to provide much of the money needed. It was probably a win-win situation for the merchant donors, as such a ‘modern’, safe bridge would encourage commerce, and flag up how well-equipped the city was to receive traders.

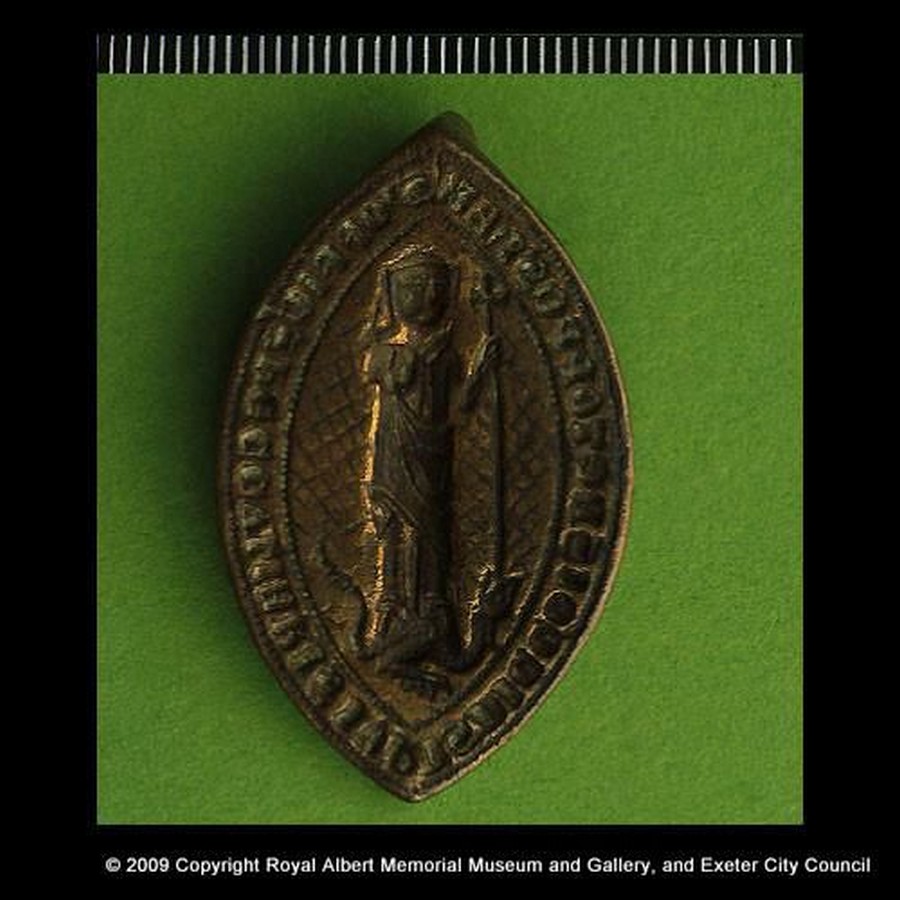

Above: The old Saxon pillar, probably once part of a cross located by the River Exe to offer spiritual protection for those trying to cross the river, in the days before there was an adequate bridge. Now in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

Praying for your soul – Chapels and Offerings

Crossing over water is always perilous; even with a relatively safe bridge in place, the gods or deity must be placated. It was common practice to throw offerings into the water before crossing a river, whether by ford, boat or bridge. Votive offerings such as coins have been found in the River Exe from different periods, along with an old Saxon cross, which might have marked the place where it was safest for travellers to cross the river. And sometimes, chapels were built on bridges themselves in the medieval period in Britain. There were originally three of these chapels on or by the Exe Bridge, of which only one, St Edmund’s Chapel, still remains, though it is now in ruins. St Edmund was rather an appropriate saint to choose, since he was a 9th century East Anglian king, who hid under a bridge to avoid capture by the invading Danes. In vain, alas, for he was caught and martyred for his faith.

Repair bills

The practical issue of funding bridges has loomed large throughout its history. (And still does – the 2nd Severn Bridge has only been free to cross since 2018, when the debt for building both bridges was finally paid off by toll fees.) Despite the relative stability of Exe Bridge, floods were still frequent, washing away stones and damaging the piers of the bridge. Tolls alone couldn’t pay for it all. Just as it was an act of charity to pay for the building of a bridge, so too was it a worthy deed to leave money in your will for its upkeep. Even small donations were welcome – in his will of 1269 Adam de Collecotte, layman, left 6d to ‘the bridge of Exeter’.

Nevertheless, even on this well-maintained bridge, floods could still endanger life; in Tudor times a tanner called John Cove and his wife were swept away downriver on their bed when their house fell into the raging torrents! Apparently he managed to paddle the bed to safety, using his hands and feet to steer it onto solid ground downstream. The servants, it’s reported, were not so lucky – they drowned in their beds.

Life on the Bridge

A bridge wasn’t just for crossing, either. No, it was for making the most of in daily life too! Exe Bridge became packed with houses, again rather similar to the buildings on the old London Bridge and on other bridges in the UK – bridges where you could shop, pray, drink, live, or store your goods. Some of these buildings on the Exe Bridge lasted right up until the 19th century, and some still remain on a few other bridges in the country. There are still shops, for instance, on the elegant Georgian Pultney Bridge in Bath.

Below: London Bridge in its medieval form.

The Long Drop

On the Exe bridge one building was known by the enchanting name of ‘The Pixy House’. The reality was not so pretty – this was in fact the first public toilet on the bridge, presumably with ‘the long drop’ to the waters below.

There was even a pub on the Exe Bridge, but along with that goes a sad story of some vagrants, who used to lodge there before peddling their ‘sulphur’ matches by day on the streets of Exeter. One night, in 1775, they accidentally set fire to their room while illicitly boiling a pot of brimstone with which to coat their matches. Some died of fumes, others when the roof burst into flames and collapsed. The pub, ironically, was called ‘The Fortunes of War’.

Holy Toll Gatherers

The spiritual significance of a bridge carried through to its mundane finances too. Hermits were sometimes appointed to collect any tolls due – it was probably mutually beneficial, since the hermit could gain from having a fixed lodging, and a modest income, and the bridge authorities would get their revenue. Most probably travellers wouldn’t usually dare to refuse the holy man what they owed! Hermits could act in other capacities too in their role as bridgekeepers –supervising repairs for instance, or acting as wise counsellors to passers-by. In medieval times they were not necessarily recluses, but often had a hut or dwelling at a cross roads, where they dispensed wisdom and were handed alms.

A less orthodox kind hermit was found on Exe Bridge, however – a female anchoress. In 1249, records relate that ‘a certain female hermit had shut herself up on the bridge of Exe and was obstructing traffic. Carts could not get by, to the grave damage of the city’s trade.’ And there she remained, for several years. It seems that no one knew quite what to do about her.

I would love to be able to wander back in time, visiting the shops on the bridge, chatting with the folk who lived there, maybe asking a hermit for a bit of wise counsel…and if I visit ‘The Fortunes of War’, I might even pay a visit to the Pixy House…

‘The View from a Bridge’

How does today’s bridge keeper feel about their task? – for there are still some of this ancient and noble calling? Here’s what one has to say:

Having worked on drawbridges for over 12 years, I’ve come to know how strongly many people feel about bridges in general. Just publish your plans to demolish or replace one, and brace yourself for the public outcry. People love to walk and jog across bridges, and many’s the time I’ve witnessed marriage proposals. Fishermen often have their regular spots staked out, and people love to hop out of their cars during bridge openings to enjoy the weather.

Bridging Worlds

A bridge may in some sense may transport us from one world to another. In myth, a rainbow bridge can lead us into the realm of the gods) or a fiery bridge to the land of demons. Or a magic bridge may be conjured up to help the hero or heroine to escape danger. There’s a sense of this in real life too, when a bridge leads us from one country to another, as with the Severn Bridge from England to Wales, or from island to mainland, as with Skye in Scotland where a bridge has been constructed in recent years. Even a tiny bridge can have major implications, such as the one from the airplane into terminal, as you leave the strange world of mid-air limbo, and prepare to step onto new and solid terrain. Bridges are ‘liminal’ places – and perhaps if we linger a little more, or at least become mindful when crossing bridges, we might sharpen our perceptions of changing from one state or place to another.

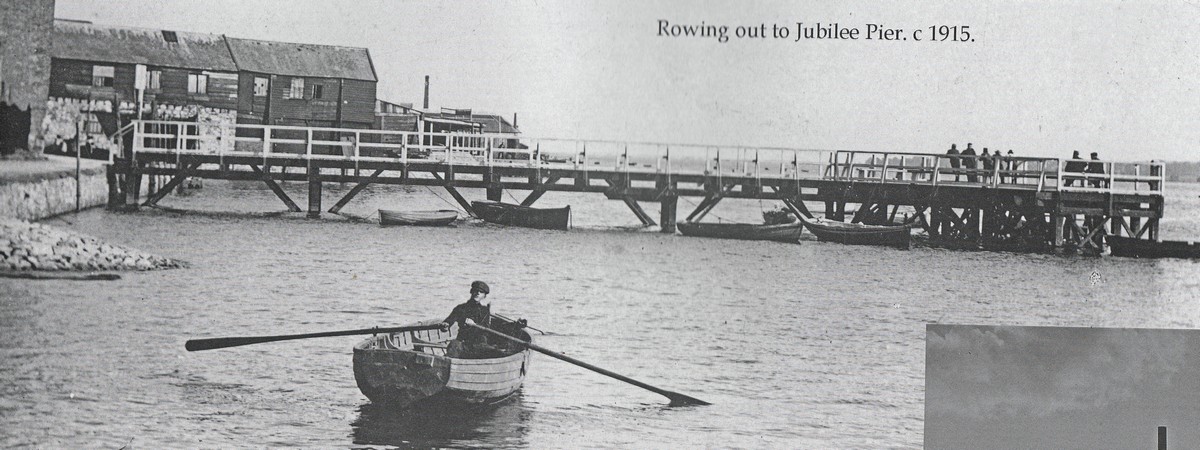

The Unwelcome Bridge

Not all bridges are benign, however. In Topsham, downriver from Exeter, there is no bridge across the river Exe. So just imagine what it would have been like in the Civil War of the 1640, when General Fairfax threw up a temporary bridge across the River Exe at Topsham, ready for marching his enemy troops over to capture the town. What fear that sight must have caused to the inhabitants! Yesterday, no bridge – today, no one is safe. Capture it he did, though not for very long…

In the 1970s, a more permanent new bridge appeared across Exe upriver from Topsham – the M5 motorway bridge. Before vehicles was allowed on it, pedestrians were invited to walk over and admire the view. Today, the motorway brige, and the noise of traffic dominates the scene upriver from Topsham. Any new bridge certainly has an impact – in this case better for some, disruptive for others.

Bridge awareness

Perhaps there’s no such thing as a bridge with no meaning or significance. And if we paid conscious attention every time we crossed a bridge we might experience this transition more intensely. Why not give it a try? Most of the time, it may be a relatively mundane experience, but sometimes it may be an intense challenge. It took me a huge attempt to overcome my fear to cross the Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge in Northern Ireland. I clung on for dear life – it didn’t matter how safe it might be in theory, it felt like dicing with ultimate danger!

Bridge Despair

Sadly, a bridge can sometimes be chosen as a place to end one’s life. The Exe Bridge of the 19th century (a replacement for the medieval one) was notorious in this respect, as we can see from various old newspaper reports. Mercifully, not all these suicide attempts were successful, though that in itself could be a serious problem. Until 1961, suicide used to be a crime in British law, so a failed attempt could lead to a jail sentence. However, judges often showed compassion:

1890 Edwin Cole aged 32, was arrested for trying to commit suicide. Witness said that at about half past nine in the morning he was standing on the Exe Bridge and saw the prisoner, suddenly throw his hat into the river, clap his hands, exclaiming, “The devil’s got hold of me.” He then threw himself into the river about fifty feet below. Cole was out of work, out of money, and rather drunk – when rescued by the witness and his friend, he said, ‘I did not want to swim ; I wanted to go to the bottom. I have had a lot of trouble, and I am tired of my life.” He was then referred to Sessions Court where he was discharged by a merciful judge after his ailing mother promised to look after him.

(A summary of the report in the Western Times).

Our modern-day Drawbridge keeper also sees the nature of bridges as a jumping off point, sometimes in a horribly literal way:

Bridges also represent transitions. “Crossing over” is a euphemism for taking that journey from life to death. Perhaps that’s also why so many people use bridges when they’ve made the unfortunate decision to end their lives, a decision which, speaking from personal observation, is made far more frequently than is reported in the media, and is also a decision which they instantly regret, judging from their screams on the way down. (‘The View from a Drawbridge)

Occasionally, a woud-be-tragic story turns into comedy. In 1885, a young woman called Sarah leapt off the Bristol Suspension Bridge after a row with her fiancé, to what she imagined would be a suitably dramatic death . However, her billowing skirts acted like a parachute, and she landed relatively unharmed in soft mud, living to marry another and surviving to the age of 85 years.

Bridge of Hope

And finally, I return to the drawbridge keeper for this positive view of the bridge:

Perhaps my favourite bridge symbol, though, is that of hope. If you can just get over that bridge, you may find yourself in a better place on the other side…So in some ways bridges can represent a struggle, but one with the prospect of better things on the far shore. I find that inspiring. (‘The View from a Drawbridge)