The second in the series ‘Tales of Tigerlily’

This is my second post about Tigerlily, the vintage clothing shop that I opened in Cambridge in 1974. As I mentioned in the first post, keeping the stock going was the biggest challenge. You cannot phone up a supplier and order six 1930s satin wedding dresses, or a genuine old Japanese kimono. You might find a dealer who would do you a job lot of collarless ‘grandad’ shirts – very popular with the guys in the ‘70s! – but probably the price would be prohibitive, as the items had already entered the retail chain, and been upgraded from ‘chuck-outs’ to desirable garments. Buying the ‘bread and butter’ items at the bottom end of the pricing pyramid, where it was up to me to recognise their potential, was the only practical option.

Collarless shirts were in fact our secret weapon. I adored the antique embroidered items that I sold, from Chinese shawls to Hungarian peasant blouses, and took my pick of silk nighties, but it was the less exotic items which made the money. I took a stall every year at the Cambridge Folk Festival, and for those few days, Tigerlily transferred its business to a tent. It was always those shirts which paid the rent and turned a good profit. We could literally sell hundreds over the weekend. Our security arrangements consisted of paying one of my helpers generously to bed down in their sleeping bag among the racks of clothes, given that the official night watch was minimal in those early optimistic years of festivals.

Where to source the clothes? Steptoe and Son come to the rescue!

On the question of resources, jumble sales were ‘entry level’ for hobby traders, as I had once been, but not a serious place to look long term if you have a permanent retail outlet. I’ll describe in a later post how we also trawled the London East End secondhand markets, but even they weren’t consistent as a source for a shop. So I asked myself the question: ‘Where do the unsold items from jumble sales go? And the clothes from house clearances?’ (You have to be a little bit ruthless in this business, realising that you’re mostly dealing with garments of dead people. It’s not everyone’s cup of tea, especially when the deceased hasn’t long left this world.) Well, there were still traces of the old-fashioned rag and bone businesses, (think horse and cart, Steptoe and Son) who took on other people’s throw-outs – I found one or two yards in London, and used to have great chats with a lively South London individual, who’d reminisce happily about life as a street urchin, having fun with his mates. ‘Mum just used to turn us out after breakfast with some sandwiches, and tell us not to come back till tea-time.’ I once bought a fabulous set of Art Deco shop scales from him, which I wish I’d never sold – they went in a trice. Pickings were slim however, even though he kept things back for me.

I then discovered a larger-scale rag warehouse in Kettering, an easy car journey from Cambridge. Probably the Yellow Pages located it for me initially, as I had no contacts there. It was a depressing and smelly place, with not a great deal to offer, but at least I learnt the form there, when dealing with employees rather than sole traders. This was to make friends with one or more of the ‘rag pickers’, ie the clothes and textile sorters, who then save the good bits for you, and get rewarded with tips for their trouble. You pay the going rate to the boss at the warehouse, by piece or by weight, usually a very cheap amount, and a ‘finder’s fee’ to your new best friend. This was a normal practice, and there was nothing underhand about it; the management accepted this, unless they wanted certain items themselves to sell on in a particular way. Our 40s dresses and de-mob suits didn’t fall into that category.

Two things were essential to this method of acquiring stock: a hatchback or estate car to pile the black sacks in, and a sturdy washing machine at home to deal with industrial quantity loads of cotton shirts and nighties. Plus it helped to have a strong constitution to put up with smells, and at least some muscle power to heave around the black sacks stuffed full of potential booty. Oh, and a good supply of cash in hand.

The Secret Sources of Yorkshire

I was still on the lower rungs of the ladder. However, one day Mick, the ‘friend’ in question at Kettering, revealed that their bales of clothes eventually migrated up to Yorkshire, to the greater rag mills of Batley and Dewsbury. I was on it, like a terrier on the scent of a rabbit! Before long, I hit the A1 up north and discovered this old clothes Mecca of England. I soon rooted out a few of these warehouses, made friends with a bunch of ladies working there, proved myself a paying customer with the management, and become a regular. We got on, had a laugh, and I made sure I never let them down – I turned up once a month, and paid the ladies well for their trouble.

The rag warehouses I visited were usually filthy places, mostly housed in old textile mills, with broken windows, and ancient groaning conveyor belts which allowed the pickers to sort the old clothes. But they were also places of wonder. Long before the days of formal recycling, they were a masterclass in how to re-use and upcycle.

‘Where are those going to?’ I pointed at a small mountain of brightly-coloured headscarves.

‘Oh, those are for Nigeria – the women love to wear them.’

‘And those?’ A drabber pile of sober waistcoats, taken from men’s three-piece suits, lay on the floor.

‘Pakistan.’

I could see it in my mind’s eye – the Pakistani men in their long kurta shirts and loose trousers, with a tailored British waistcoat over the top. Smart!

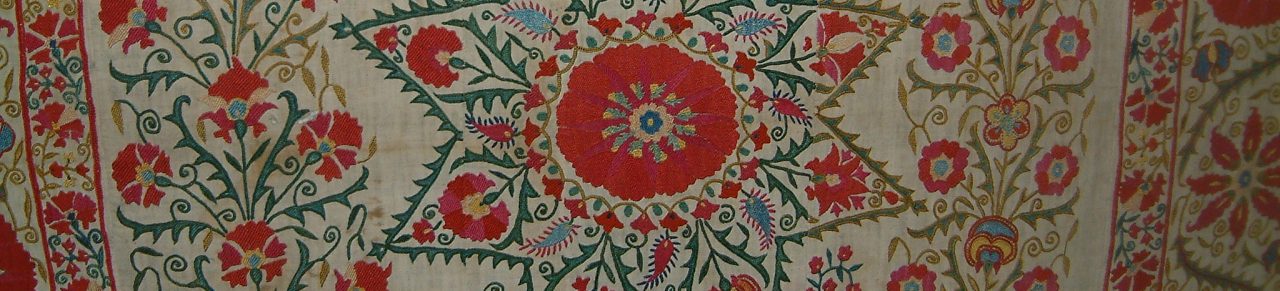

I marvelled at the jewel-like heaps of woollen garments were dotted around, literally in all the colours of the rainbow. Wool could be re-spun into second-grade yarn, and by sorting the items into colours into blue, green, red, yellow, pink, purple and so on, they could be processed in batches.

Crimplene dresses (remember those?) were for ‘the market women’ who ran the second-hand stalls. The ‘hippy gear’ – the vintage clothing – was for people like me. The only thing which couldn’t be re-cycled or re-purposed, I was told, was the material that suits were made from.

‘It’s only good for cardboard.’

But even that gave it a place in the recycling chain. I was amazed at the time, and had ambitions to write an article about it. Sadly, I never did, and I have no photographs either of these extraordinary places. Those in this article are ones I’ve been kindly lent or discovered much later, but they do not show those rainbow piles of wool or cheerfully-patterned scarves.

These photos, from a rag warehouse in the area show the basic equipment used in the sorting process – baskets, nylon sacks and wooden troughs. I brought home some sturdy shallow baskets, plus a number of the bags, which came in handy for years as storage.

While I was visiting these warehouses, I kept an eye out for garments that I might wear, and I picked up some good-as-new cashmere jumpers. The Harris tweed women’s jackets were fabulous too, and just about ready for a fashion revival. This was the thing – you had to have an eye for what was desirable or funky – the image that people wanted to wear. But age and period weren’t everything; even some really old items weren’t funky or stylish enough – they could be too large, too short, or too worn to tempt customers. Our clothes were sold fairly cheaply and were not always perfect, but they still had to be the right fashion for the present moment. ‘50s clothes, believe it or not, were despised, apart from some of those strange old American baseball jackets. You might get away with selling a full cotton rock-and-roll skirt, if you were lucky. At that time, twenty years was all that divided the ‘70s from the ‘50s, and I believe that it’s at least a thirty year gap before styles begin to come back into favour again. Though does that mean that the 1980s are cool now?

A Tigerlily customer remembers:

‘Bought an American style Baseball jacket from here many years ago, early 80s I think, it was black but with red pvc style arms, people would stop me in town and ask where I purchased it, it started quiet a trend back then, rockabilly style with skintight jeans, basketball boots (hi tops) and my hair in a flat top, I felt the dogs Bo**ox in it’. Paul Blowes, via ‘Cambridge in the good old days’ Facebook page.

The other side of the coin

The warehouses could also be dangerous places – some that I visited were housed in former textile mills, with broken windows and rickety wooden stairs. Fires broke out on at least two occasions I was there, probably from people smoking carelessly around piles of textiles. Although I loved my trips to the mills, I couldn’t help but observe that in one or two of the mills that I frequented, there was an inherent male bullying culture which made for a volatile atmosphere. The women there told me about the hardships of their lives too, and many were on anti-depressants, which were handed out by their GPS like sweets in that era, with no warning of possible addiction. One day, I witnessed a very young woman, probably still a teenager, who was sobbing her heart out because someone had just drowned a litter of kittens born in the mill. I could really feel with her and for her, but at the same time recognised that she’d have to toughen up if she intended to keep working there. Having said this, other mills were cheerful places, better run by dedicated family firms.

However, whatever the state of the building or the problems of management in the rag mills I knew, I was greedy for the treasures that might be buried in such smelly and sometimes repellent piles of clothing. Just as the alchemical gold is said to be forged from a ‘primal substance’, something base and dirty that everyone overlooks, there was much here which could be redeemed and transformed into new use. And occasionally, there was real and recognisable treasure to be found – one or two pickers who I met had found gold coins and jewellery in the pockets of worn-out clothes in the bales!

I remember those mills with curious affection, and nostalgia. I’d like the chance to pick up a Harris Tweed jacket there today, and some top-of-the-range cashmere sweaters. And although I don’t miss the stink of old clothes and rooting through piles of dubious textiles, I miss that sense that any moment now, I might stumble upon something extraordinary and beautiful.

I would dream of finding my own treasures, such as a gorgeous vintage dress as below. This one is probably from the early 1930s and is most definitely not from a rag yard, but is kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Acknowledgements

The fascinating life and history of these businesses has largely gone unrecorded, to my knowledge. I had no photos of my own, and internet pickings are very slim. So I am very grateful to Judith Ward for offering me photos of her family’s warehouse, taken just before it closed down in 2009. This was not one that I visited, but the shots remind me of what I’d typically see on a clothes-hunting expedition.

Please note that none of the comments about my own experiences relate to this particular business.

You may also be interested in:

Tigerlily in Cambridge