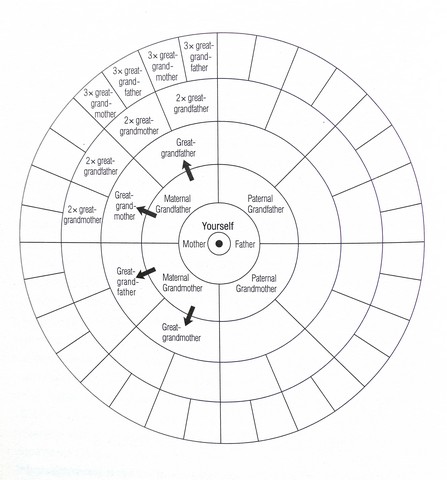

In the last post, I suggested one way in which we can get to know our ancestors, by plotting the relationships between us, and contemplating the circle which they form around us. This current post now moves away from the charting of ancestry, to focusing on some of its spiritual aspects, and considering whether our line of ancestry may still play an active part in our lives. As we now head towards Halloween, based on the ancient Celtic festival of the dead, it’s the season to speculate more about the possible dimensions of life and death, and how we may connect to these.

I’ll also mention the role of shamanism in connecting us to our ancestors. Shamanism is, in essence, an ancient belief system of inter-penetrating worlds of spirit, in which we can play an active role. It includes both animate and inanimate forms of life, in modern terminology, and the realms of both the dead and the living. The ‘religion’ of shamanism – using the term loosely, for there are many versions of it – may once have been widespread throughout the world in its various forms, fundamental to many if not most cultures, including the greater part of Europe. And it contains the belief that journeying between these worlds is possible, often with the assistance of a shaman. Although such travelling must be done with care, it can help us to access knowledge, including foreknowledge, the power of healing, and positive forces which can guide us through life in this middle world.

The otherworld of the ancestors

In the Western world, although this shamanistic world view has largely been abandoned, there are still traces of it in folk lore and myth, as reflected in this ancient poem from the north of Britain. It reveals that a soul must travel a particular path at the time of death, to make the transition between worlds and reach its new dwelling place. Here in the poem, this sanctuary is that of Christ, combining the older world view with that of Christianity. (See Jeff Duntemann’s post ‘Understanding the Lyke Wake Dirge’ for a translation into modern English.)

A Lyke-Wake Dirge This ae neet, this ae neet, (night) Every neet and all, Fire an' fleet an' candleleet, And Christ receive thy saul. (soul) If thou from here our wake has passed, Every neet and all, To Whinny Moor thou comes at last, And Christ receive thy saul. And if ever thou gavest hosen or shoen, (shoes) Every neet and all, Then sit ye down and put them on, And Christ receive thy saul. But if hosen or shoen thou ne'er gavest nane, (none) Every neet and all, The whinny will prick thee to thy bare bane, And Christ receive thy saul. From Whinny Moor when thou mayst pass, Every neet and all, To Brig o' Dread thou comest at last, And Christ receive thy saul. From Brig o' Dread when thou may'st pass, Every neet and all, To Purgatory thou comest at last, And Christ receive thy saul. And if ever thou gavest meat or drink, Every neet and all, The fire will never make thee shrink, And Christ receive thy saul. But if meat nor drink thou ne'er gav'st nane, Every neet and all, The fire will burn thee to thy bare bane, And Christ receive thy saul. This ae neet, this ae neet, Every neet and all, Fire an' fleet an' candleleet, And Christ receive thy saul.

As far as I know, there are no tunes extant to this old rhyme, althought various arrangements of it have been made. But this recording made by the Young Tradition folk group in 1965 resonates with the spare harmonies of earlier periods, and sounds like a ritual chant as it announces the path of death which must be trodden. This is likely to have been its original function, chanted over a dying or dead person, to guide their soul on its way.

And if you’re up for another song, this one was composed in recent years, but commemorates another very old custom. ‘The Old Lych Way’ tells of how a body in a coffin on Dartmoor had to be carried right from its home parish, perhaps a tiny hamlet on the moor, to the church at Lydford, which alone was authorised for burial. It could be many miles, for the bearers and the mourners to trudge. The song, by Topsham musician and friend Chris Hoban, is here performed by his colleagues in the folk group ‘Show of Hands’.

And after that, let’s move on from the death of the human body to what might be your ancestors’ presence in another realm.

The long line of ancestors

For many of us who embark on researching family history, it becomes more than just creating charts and checking out parish records. It can bring a sense of a living connection with our ancestors. When I was gathering material for my book Growing Your Family Tree, I conducted a survey for readers of a family history magazine, enquiring about their experiences of researching their family tree. Many of the respondents reported that after doing the ground work, they felt their ancestors were in some sense becoming ‘alive’ to them. And some also mentioned that strange occurrences began to happen during their research, such as unexpectedly discovering new family connections, as if the ancestors were eager to reveal themselves. It seems that when we start paying attention to our ancestors, various synchronicities and surprising events may happen.

The Welsh Voices

Here’s one of my own experiences of this kind:

It happened one summer night, a few years ago. I had been working on my Welsh line of ancestry, trying to figure out the branch of the tree which I could now trace back to my 3x great grandfather, Edward Owens of Abbeycwmhir, the soldier in the Napoleonic Wars.

All that night, my sleep was disturbed by what seemed like a babble of voices. I heard people chattering insistently, and I knew that they were my Welsh ancestors. I could not make out what they were saying, but I had the distinct impression that they wanted to be ‘found’ again, and that they wanted their story to be told. Edward’s own insistence came through, and I inferred that his special wish was for his prowess as a soldier in the Napoleonic Wars to be remembered, and perhaps for his medal to be found again.

This might seem like fantasy. However, it made a profound impression on me, and within a couple of months extraordinary things started to happen. A seemingly random hit on a website for a Welsh chapel led me to finding two separate lots of new cousins, also direct descendants of Edward Owens, whose families were still living in the same region as my ancestors in mid-Wales. I had thought previously that everyone had moved away from the area. When I met up with Harold, my third cousin, he shook my hand, looked deep into my eyes, and said, ‘You’re the first member of the family to come back for a hundred years.’

I was swept into a whirlwind of activity on that first expedition. With these two families I looked at photos of my ancestors that I had never seen before, heard anecdotes about their lives, including those relating to a 2 x great aunt who was a midwife and a herbalist, and shown of the local places associated with them. I also saw pieces of furniture actually made by our joint 2x great grandfather, who turned his hand to cabinet-making as the small stipend he received as a minister couldn’t support his family. Beautifully made, of polished oak, the cupboard and two tables took my breath away as I touched the work that my ancestor had created. After this, research went like greased lightning in the Powys Archives, and I was also able to trace the existence of Edward senior’s medal up until its last publicly-recorded sale in the 1970s. The speed at which all this unrolled was incredible. I felt that I had unlocked a door to the past, and that the wish of the ancestors to be known and acknowledged by their descendants had a kind of volition of its own, which fuelled my search.

All this has fed into my current network of family connections. Cousin Harold and I have kept up our acquaintance, exchanging cards and phone calls every Christmas. Likewise, I keep contact with others of the new-found cousins, one of whom ended up living very close to us for a while. My only sadness is that my mother never knew about this branch of the family. For the last thirty-five years of her life, she lived in Church Stretton in Shropshire, which was less than thirty miles from her cousins over the hills in Wales. She would have loved to meet her relatives there!

The Ancestors and our Spiritual Heritage

We are unusual in the Western world, where the prevailing culture doesn’t generally consider the ancestors to be a direct influence in our lives. Our deceased relatives are remembered fondly (or otherwise!), stories may be told about their lives, and graves tended for a while. But that’s generally as far as it goes. Many if not most other cultures around the world, however, consider the ancestors to be a living presence. Although they may inhabit another dimension, their world and ours can interact. This may at first strike the Western mind as naïve, or reeking of old-school Spiritualism, but if you study these different belief systems, it becomes apparent that they can be subtle and sophisticated in their appreciation of different forms of consciousness.

And a sense of this interdependence can also be used for specific purposes. For instance, in Tuva, Siberia, if a man or woman feels called to become a shaman, they may try to draw on their connection with a particular ancestor who was a shaman, and link in to their power and knowledge as a source for their own initiation. Unlike some New Age perceptions of shamanism, it’s often a calling that a Siberian would rather not experience. The commonest way of realising that they are being compelled to become a shaman is through falling into a period of illness or intense suffering. It’s more a case of giving into the demand, rather than seeking it out. And in which case, a contact with an ancestor who was also a shaman may be the best way to tread the right path and set the seal on it.

In shamanism, drumming and chanting can be a way to communicate with the ancestors. This also means opening up the threefold world, and going beyond our human ‘middle world’. Spirits of the dead usually inhabit the world below, and sky spirits or transcended spirits inhabit the world above, according to this shamanic world view. And once this connection is established in a conscious way, the shaman has a pathway into the world of the spirits. It means that he or she can then regularly practice rituals to awaken the connection, which serves as a channel for wisdom, healing or prophecy, according to whatever is required by those who need their help.

The Way Forward, with a contribution from R. J. Stewart

Shamanism is thought to be the most ancient of religions, and interest in it is growing again in the modern world. There is an eagerness among many spiritual seekers to work with their own form of shamanism. But how do you go about this, and does it work? Can it be done by blindly copying the practices of existing traditional shamans – in Siberia, South America or Africa, for instance? Perhaps a more authentic way forward is to re-connect with our own ancestors, and learn from them if we can. Author R. J. Stewart, an expert in Celtic mythology and the Western tradition of magic, has kindly contributed this post which sheds light on a controversial question:

Between the late 1980s and the mid 90s I had several meetings with Native American Elders, often to compare what is known as “Celtic” tradition today, with aspects of their multifold traditions. When the first contingent turned up unexpectedly at a talk I was giving in a bookstore in Greenwich, Connecticut, I felt as if I was on trial…as indeed I was. Subsequent private meetings relaxed into a degree of mutual trust, resulting in a potential invitation to join the World Council of Tribal Elders, to represent Celtic tradition, in a forthcoming gathering in Australia. The elders were especially critical of New Age shamanism, which they saw as form of alternative popular psychology, and not truly shamanistic. We agreed on that.

As I was unable (though not unwilling) to attend, the invitation was never formalized. A few memories of our meetings stand out for me, and we seemed to confirm to one another that a proportion of my Scottish ancestral traditions shared certain truths and magical practices with theirs. We talked a lot about revenge and forgiveness, ancestors and spirits. Two examples will have to suffice here:

1 – Spirits through the fire. During a convivial meeting with Grandmother Kitty the log fire exploded into extra flame very dramatically then died right back only to resurge, three times. As in old Gaelic tradition, such manifestations are not commented upon when they occur, but silently acknowledged, perhaps with a slight nod of the head. The next day her apprentice (a mature woman) said “Grandmother instructed me to ask you how many spirits came through the fire last night ?”. I answered “There were three spirits that came through the fire… I sensed them, but could not tell what they intended”. That seemed to be acceptable. There was no “teaching” no “wisdom transmission” just mutual silent acknowledgement. At one point, though, Grandmother had said something that I could not fail to forget: “We do not want your people adopting our traditions. You have your own traditions to feed and care for. When your people are mature again within their own traditions, we can all come together in peace at last”.

2 – Ancestors: on another occasion, Big Toe Hears Crow looked at me and laughed. He said “We feel sorry for you white folks…you only have your miserable human ancestors. We have birds, animals, forests of trees, and even entire mountains”. He had a habit of humorous provocative utterances. And again: I was talking about the Wheel of the Year (at the bookstore mentioned above) and asked if anyone in the audience had examples in their own understanding or tradition. Big Toe quietly said “ Well, just like you, we have the East and the West, and then..hmm…yes… there is the South and the North. And there is a Buffalo in there somewhere, but the Buffalo moves around a lot”.

Both of the elders that I mention here have passed on into the spirit worlds in the years between then and now. Not all of my ancestors are miserable, except perhaps some of the Calvinists. One “went native” in South Africa in the late 19th century, where he was renowned at spirit healing. He surely found a wandering Buffalo.

Note: The correct bovid name is “Bison” for North America, and “Buffalo” for Africa. But the ancestors do not seem to care.

R J Stewart 2023

Books by R.J. Stewart include The UnderWorld Initiation, The Well of Light, and The Spirit Cord

Involving the Ancestors

I have written elsewhere about my own visit to a wise shaman in Kizyl, Siberia, in 2005 – see ‘Meeting the Shaman in Siberia’.

During this session, with chanting and drumming, he endeavoured to drive out the ‘bad energy’ or misfortune, which he identified as lodging in my shoulder –indeed, I did tend to ‘shoulder’ burdens. I can interpret this in a straightforward way, since I’d had a period of trouble and ill health. However, just as the ritual involved Herel connecting with his own ancestors to help him, so I sense that my own ancestors may have been involved too.

For several years before this trip, I had been researching my family history, which was mostly a pleasurable experience, with stimulating discoveries. However, quite early on in the process I had a different kind of experience, which I can only describe as a spontaneous vision happening on the borders of sleeping and waking. It seemed that a whole procession of dark, shadowy forms was marching right through me, coming in through my back and emerging from my chest. They seemed oppressive, somewhat sinister, and even threatening. I sensed that they had emerged from my ancestral past, and that something connected with fate was unfolding. It was a time when my own life balance was shifting in a profound way.

However, after the visit to Siberia some seven or eight years later, I returned to the UK via Moscow, and en route recorded in my diary:

Woke up 5am after 7 hours solid sleep – with an impression of my relatives and ancestors at my right shoulder, flowing out of it in a wavy shape like a kind of stream. A warm and light quality to it.

So perhaps the shaman’s ritual had actually relieved that heaviness in me, removing the weight of a negative aspect of my ancestry? At any rate, it certainly seemed that something had now been transformed.

The paths of ancestry may run deeper through our lives than we imagine, and it may be understood better than we might think by the ancient practices of shamanism. I can only speculate how that works – whether, to put it in a rather crude way, a shamanic ritual can work like unblocking a clogged conduit, so that the water can run free and clear again. Perhaps it helps to balance out energies, as anyone’s ancestry is bound to be a mixture of forces, some outdated and needing to be left behind.

At any rate, the season of Halloween is an appropriate one in which to remember and honour our ancestors. Amidst the jolly, scary ghouls and witches trick-or-treating round the town, perhaps we can take time also to quietly recall those who have come before us on the ancestral path, and to cherish their memory. They are not lost, for indeed, we all share one ‘common life’.

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to R. J. Stewart for permission to include his account of conversing with the Native American Elders.

And to Herel, the shaman of Kizyl, Tuva, who remains a bright presence in my mind.

Plus the organisation known as Saros, which explored notions of ‘common mind’ with the motto that ‘there is always somewhere further to go’. Its history and purpose can be discovered here. Offshoots of Saros can be found here