I have always admired William Blake as poet and artist, and have a battered copy of his poetry from university days. But shortly after I left university, as I began to explore the practice of meditation, and the philosophy of Tree of Life Kabbalah, his work became even more meaningful to me. He was a natural visionary, but behind his blazing revelations and frequent conversations angels and spirits from another realm, there appeared to be a kind of philosophical framework. How did that come about? And was it really similar in some ways to the Tree of Life, which I had been studying?

Further reading revealed that he was a man of some knowledge, as well as a spontaneous mystic. This was still somewhat at the fringes of scholarly research into Blake, however. Although Laura de Witt James had already published her study of ‘William Blake and the Tree of Life’ in 1956, it didn’t hit the bookshops widely until it was republished by Shambala in 1971. Following these scanty leads, in the mid-70s, I persuaded my husband that we should take a long detour, while on holiday in Devon with querulous small children in tow, to see Blake’s famous ‘Sea of Time and Space’ picture which then hung at Arlington Court. I can’t say that I understood it at the time, but it definitely pointed towards a more structured understanding of the spiritual nature of the universe.

Blake wrote in one of his letters:

‘Temptations are on the right hand and left; behind, the sea of time and space roars and follows swiftly.’

My connection with Blake over the years remained enthusiastic, if mostly unscholarly. When the Tate housed a recent major exhibition of his work in 2019-2020, I travelled to London twice to view it, , and marvelling over his paintings and engravings for hours each time. The vibrancy of his work in its original form has a presence which surpasses the experience of seeing it in print.

But at the same time, I decided to pursue a new line of enquiry, which began with a conversation with the author R. J. Stewart, a specialist in magical and esoteric traditions. I hoped to find out more about Blake’s connections to these traditions, a theme which is close to my heart. (See ‘Soho Tree’, a blog I co-write with Rod Thorn.)

I should warn you that this is a somewhat long article! You may prefer to scan it, and enjoy the visuals and video clips, or pick out the sections of interest. Don’t miss the exotic Count Zinzendorf… I emphasise again that I am not a Blake scholar – I’ve merely drawn on the findings of others, and have endeavoured to make these more accessible. I feel that this element of Blake’s work deserves to be more widely known.

William Blake, 1757-1827 and the Moravians

A few years ago, therefore, R. J. Stewart told me that William Blake’s parents had belonged to the Moravian Church in London. This was news to me, and I decided to try and find out more. With the access I had at the time to JStor, that wonderful repository of academic articles, I was able to follow the trail which certain modern scholars have opened up. (I give the sources for these at the end.) No doubt there is more information and possibly argument to come, but even as this early research stands, it brings an extraordinary new view of Blake’s mystical affiliations and practices.

The question turns on the religious allegiance of the Blake family. They were known to be Protestant dissenters, but speculation hadn’t previously managed to pin down what type of sect they belonged to. Even when Peter Ackroyd wrote his major biography of William Blake in 1995, nothing definite was known, and he considered that the issue wasn’t of great importance: ‘The identity of that sect has never been determined…It is of no consequence at this late date.’ He accepted, however, as most other scholars have done, that Blake’s family had some connection with the the followers of Emanuel Swedenborg, the 18th c. Swedish scientist and mystic. For the Swedenborgians, conversations with angels and knowledge of the higher realms of beings was central to their practice, and this is something s certainly reflected in Blake’s own visions and writings. But just over ten years after Ackroyd wrote the biography, new evidence came to light.

Catherine Blake and the Moravians

One of the most important new discoveries is that William Blake’s mother Catherine had made an earlier marriage to a Thomas Armitage in 1748, before she married James Blake, William’s father. And it’s on record that both Catherine and Thomas were both members of the Moravian Church. There had been earlier, inconclusive hints from writers on Blake that the family had Moravian connections, but these hadn’t been taken very seriously, especially without firm evidence. However, the Moravian archive at Muswell Hill has now yielded the evidence which confirms this. This also scotches the notion that the Blakes were ‘Muggletonians’, a curious sect who based their belief on the Book of Revelations.

And now further investigation is revealing how much influence the Moravians may have had on Blake’s upbringing, along with his sources of inspiration. This Moravian connection also includes links to Rosicrucianism, the teachings of the alchemist and mystic Jacob Boehme, and to Kabbalah. ‘Through their association [the Blake family] they enjoyed unusual – even unique – access to an international network of ecumenical missionaries, an esoteric tradition of Christian Kabbalism, Hermetic alchemy, and Oriental theosophy, along with a European “high culture” of religious art, music and poetry.’ (Schuchard)

Catherine, Blake’s mother, was granted admission into the Congregation of the Lamb, which was the elite group at the heart of the church. The letter of application she wrote is still extant (Moravians are known for their detailed documentation of personal lives), and shows that she was a fully committed member, rather than an occasional attender. This letter would have been read out to the Congregation for their approval, but applications had to be further tested through the ‘drawing of the Lot’. Human decisions were put to the test of holy divination -‘the casting of lots was seen as God’s intervention in directing human affairs.’

It’s likely that William Blake’s uncle and aunt (on his father’s side) were also members of the Church –Brother and Sister Blake, Butchers of Pear St were also referred to in the records. Catherine’s first husband Thomas died in 1751, only three years into the marriage, and she married James Blake in 1752. She may therefore have met her second husband and his family members through this Moravian Congregation.

Surprisingly, it was perfectly acceptable to be both a member of the Moravian Church and the Anglican Church. In fact the majority of the English Moravian Brethren followed this practice. Their religion was officially classified as ‘episcopal’ and as a ‘sister church’ to the Church of England. Nevertheless, the law demanded that their places of worship should be licensed as Dissenting Chapels. It was probably from this odd hybrid, that the traditional scholar’s view of the Blake family as ‘radical dissenters’ grew up, even though they were in another way within the fold of the official Anglican church.

Origins of the Moravian Church

‘The Hussite movement that was to become the Moravian Church was started by Jan Hus in early 15th century Bohemia, in what is today the Czech Republic.’ The Moravians were classed as Reformist and Protestant. But after various upheavals in Bohemia, when Catholic influence was restored, the Moravians ‘were forced to operate underground and eventually dispersed across Northern Europe.’ The chief remaining communities of the Brethren were thereafter located in Leszno in Poland, andas small, isolated groups in Moravia. These latter were referred to as “the Hidden Seed” which Bishop John Amos Comenius prayed would preserve this faith.

Comenius himself had Rosicrucian links, including a friendship with Johann Valentin Andraea, the putative author of the mysterious and significant Rosicrucian Manifesto and/or The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz. These have retained their mystique in Rosicrucian and alchemical circles right up to the present day. So the influence of the Rosicrucian movement too probably fed into the Moravian Church’s philosophy.

The Moravian Church in England and its Teachings

Once the Church, known as Unitas Fratrum, was displaced from Bohemia, it established branches in England too, where it was known as ‘The Renewed Church’ from 1722 onwards, the period relevant to the Blake family. The first Moravian ‘missionaries’ arrived in London in 1738, spending a few months there on their way to America. (America proved fertile ground for the Church to take root.) They took John Wesley (brother of Charles and co-founder of Methodism) into their religious group, and there was a degree of mutual influence, although he later separated from them. By 1742 they were ready to lease a Meeting House in Fetter Lane, which then became the main London HQ and Chapel for the Moravians for the next 200 years.

Swedenborg himself attended Fetter Lane Moravian services and became friendly with members of the congregation. This too may have had a direct influence; his visits were in 1744-5, during the year he spent in London, and around the time of Catherine’s early involvement with the Church, before Blake was born. There is also a historic claim that Blake’s father was a Swedenborgian, which is as yet unproven.

The main centre of Moravian worship in London remained at the church in Fetter Lane, until it was bombed in World War Two. The Moravian Church Library and Archive, where much new Blake material has been discovered, is now in Muswell Hill (north London). The Moravian Cemetery is in Chelsea/Fulham and it looks as though worship is still carried on in the chapel there. Details here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moravian_Burial_Ground, and also here. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/fetter-lane-moravian-burial-ground. There are also still a number of Moravian churches in the UK, and by chance, a few years ago I happened to drive past the biggest Moravian centre of all at Fulneck near Leeds in Yorkshire, with its magnificent buildings.

The Moravian Philosophy

The Moravian Church philosophy was to seek transcendence and joy in the context of everyday life, and to aspire to Unity. It was considered important to ‘be still’ and await God’s grace, rather than becoming too fervent in worship. (Something we might consider to be in harmony with the contemporary interest in meditation, and with enabling a personal connection with spiritual experience.) The Moravians also attempted to reconcile the teachings of Judaism and Christianity, and carried a semi-secret Christian-Judaic form of Kabbalistic teaching – which, as mentioned earlier, accords with Blake’s own acquaintance with the tradition.

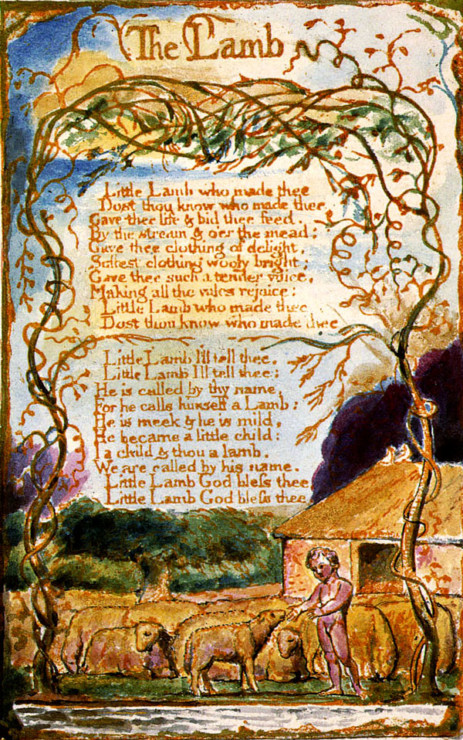

The Lamb (as in the Congregation of the Lamb which Catherine joined) has been a key symbol for the Moravians, with strong mystical associations. It sheds light on Blake’s use of the Lamb in his poetry, and his frequent references to sheep and shepherding.

The concept of the divine feminine has also been extremely important to them. There are mentions in their hymns of the Shekinah, the female emanation of God who is found in the Kabbalah and in mystical Judaism. At the time of Blake’s upbringing, they believed in treating children gently, and introducing them to art and music in mystical contexts early in life. They also encouraged home schooling, considering that the best teacher was the child’s own mother. In the church, special services were held for children, with plenty of singing; reports declare how joyful some of these occasions were. Overall, the Moravians were renowned for good pastoral care, and members could request one-to-one visits for a form of counselling – Catherine Blake, William Blake’s mother, requested this herself.

Love Feasts

Becoming a full member was very time-consuming and involved many monthly meetings, plus ‘love-feasts’. These may sound extraordinary today – the feasts involved a sensual identification with the body and wounds of Christ. Followers were encouraged to visualise holy scenes of Christ, and to feel like active participants in these. (A modern and more restrained version of the love feast in America is described here https://www.moravian.org/2018/11/the-lovefeast/ .) So visualisation and imagination played a key part in their religious practice, which again chimes in with Blake’s own approach to writing and art. There is also an erotic element to this mysticism which has recently been explored by academic Marsha Keith Schuchard in William Blake’s Sexual Path to Spiritual Vision. However, overall propriety of conduct was always emphasised, and stricter than it is today. Men and women were strictly separated, but seem to have played an equal part in the church. One John Blake (possibly William’s uncle) was expelled from the elite Congregation for flirting with a ‘Single Sister’!

Mystical Calligraphy

Among the Moravian mystical practices was that of ‘Frakturschriften’, defined as the ornamental fracturing or breaking of letters. It seems to have been a kind of contemplative calligraphy where the letters were allowed to break up into whorls and flourishes and labyrinthine patterns. This became a speciality at the community of Ephrata, in Pennsylvania, which operated on principles drawn from the teachings of Jacob Boehme and the Rosicrucians. The notion of writing sacred letters and the names of God, in a meditative state, is of course found in other traditions, in particular as another aspect of mystical Kabbalistic ‘letter permutation’. It also has resonances with the Christian pre-Reformist Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life in the Low Countries, who worked mindfully with calligraphy both as a religious practice and as a way of earning money.

Count Zinzendorf

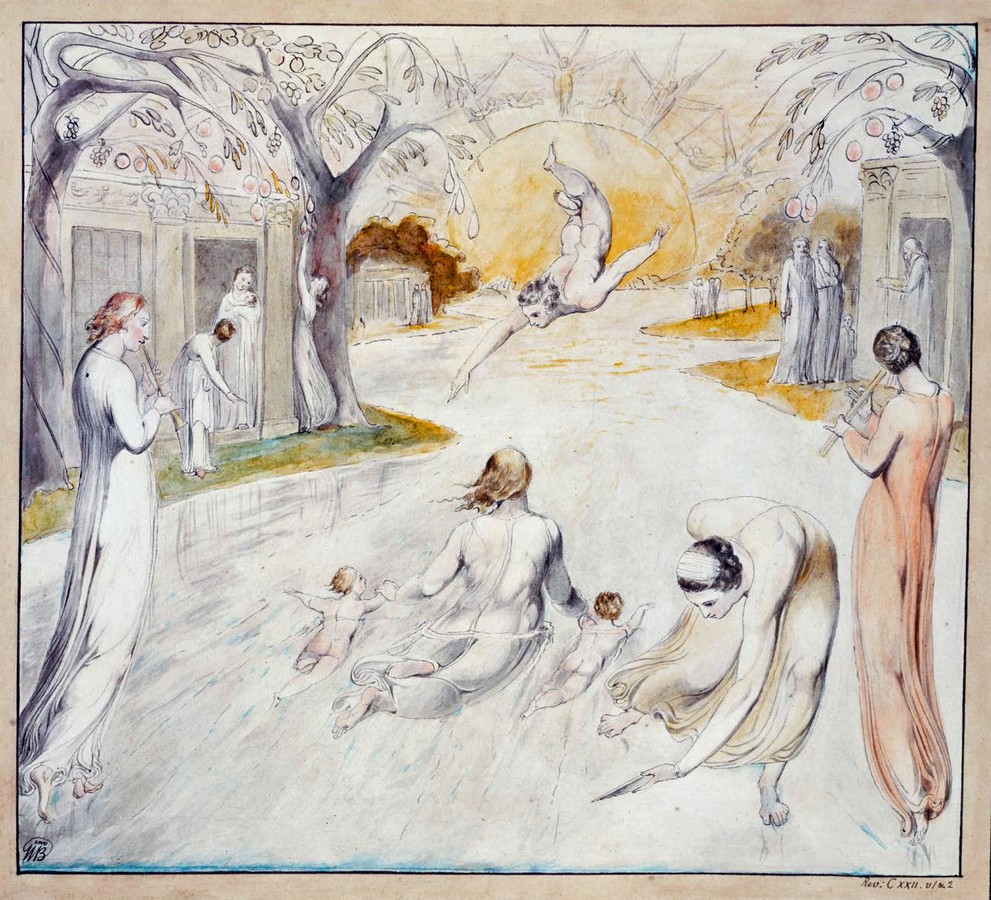

One of the most important figures on the Moravian scene was Count Zinzendorf (1700-1760), leader of the Unitas Fratrem movement in the Moravian Church. A fascinating and flamboyant character, he paid visits to London from his base in Saxony, at a period which coincided with the Blake family’s church membership. His input helped to cement the London congregation that threatened to fall apart when John Wesley left it in 1740. More remarkably, though, he also influenced the Moravians by promoting a kind of full immersion into a fusion of vision, music and mystical experience. Demonstrations took place at Lindsey House, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, once Zinzendorf’s London home. (It is now National Trust but not usually open to the public.) Both here and in the Fetter Lane Chapel, the walls were painted with mystical scenes, and further images were also projected by lanterns or candlelight. The practice was to gaze at these, sometimes with music playing to heighten the experience. It was an unusual experience for the 18th century, to say the least!

To us today, it might seem gruesome, since there were often bloody images of Christ’s wounding and crucifixion, and in contemplating these, followers sought a kind of intense combination of agony and ecstasy. And Zinzendorf believed that this wasn’t an ‘adults only’ experience; he advocated that mother and child should contemplate these together, and that even pregnant women should mystically assimilate these images to influence the baby in the womb. (No X ratings or ‘over eighteens only’ held sway at Lindsey House!)

Blake and the Moravian influence

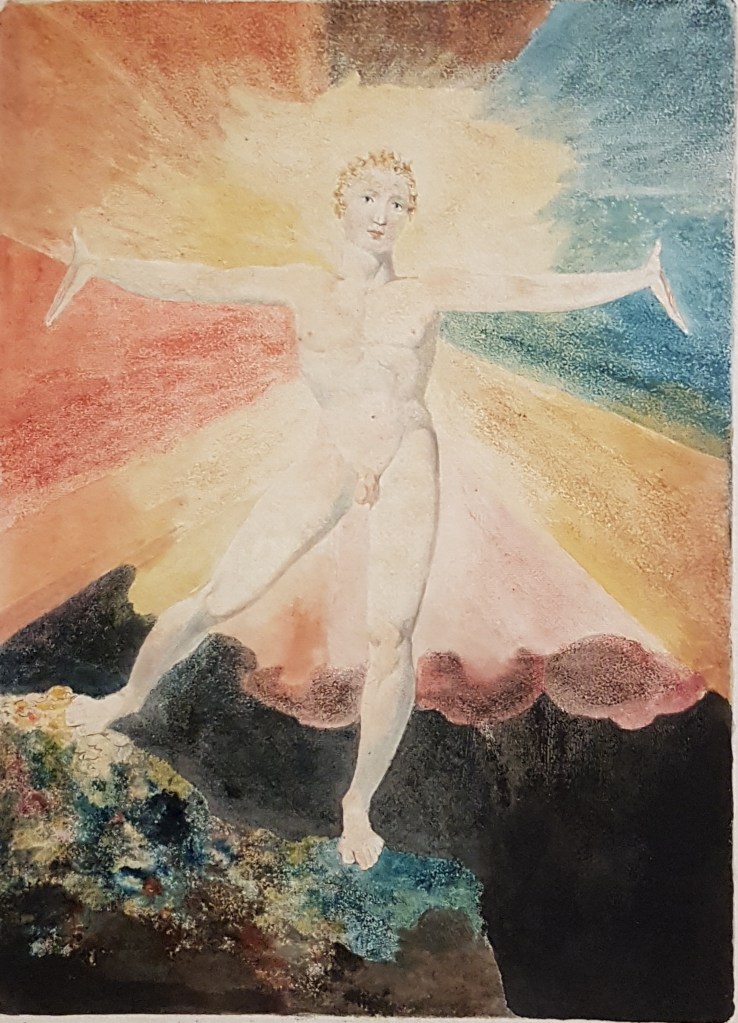

The importance and power of language, especially when combined with music and imagery, would have been brought home to Blake in the Moravian context. The obvious correlation in his own work are his Songs of Innocence and Experience, where poetry and images are intertwined, beautifully and symbolically. We don’t know whether he directly experienced love feasts and lantern gazing, but the influence would have been within the family experience of Moravian practices. And his polarised view of primordial, bright ‘innocence’ contrasting with the suffering of ‘experience’ certainly resonates with the unusual Moravian culture.

Other papers on this topic also emphasise the connections between Blake’s own writings and the Moravian outlook on parenting, mysticism and indeed its music. Moravian hymns bear a strong resemblance to some of Blake’s poetic forms. You can listen to modern recordings of these. I’m struck by their pleasing, tuneful quality; they have an appeal which is innocent and fresh. Some are within the more mainstream repertoire of church music, and probably many of us have sung a few over the years without realising where they came from.

And we can imagine William Blake, as a young boy, sitting on his mother Catherine’s knee, as she sang these to him as nightly lullabies.

Morning Star I follow thee’

Lead me here or lead me there:

Thou my staff in trav’ling be

I’ll no other weapon bear;

Me may Angels guard from ill,

When I am to do thy will:

So shall I with steady pace

Reach the dearest City, Grace.

Blake’s own faith therefore may have been profoundly influenced by the Moravian religion and worship. It may have given, at least in a part, a framework for his psychic and mystic experiences. Possibly, too the contrast between their fostering of the love and innocence of childhood along with a strictness about sexual separation may have induced a dichotomy in Blake which revealed itself in his Songs of Innocence and Experience. I’ll end with some quotes, however, that I have taken from Blake his letters, to show his own very personal and intense connection to nature as a sacred force and to a realm of spirit which lies beyond the senses:

‘I know that this world is a world of IMAGINATION and Vision. I see everything I paint in this world, but everybody does not see alike…The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way.’

‘I know that our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago I lost a brother and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the Spirit and see him in my remembrance in the regions of my imagination. I hear his advice and even now write from his dictate…it is to me a Source of Immortal Joy: even in this world by it I am the companion of Angels…The Ruins of Time builds Mansions in Eternity.’

‘That which can be made explicit to the Idiot is not worth my care. The wisest of the Ancients consider’d what is not too explicit as the fittest for Instruction, because it rouses the faculties to act. I name Moses, Solomon, Aesop, Homer, Plato.’

And when Blake died, George Richmond wrote to Blake’s friend, the artist Samuel Palmer:

He said he was going to that country he had all his life wished to see and expressed himself happy…Just before he died his countenance became fair. His eyes brighten’d and he burst out into singing of the things he saw in heaven.

Blake’s ‘Tiger, TIger’ – possibly his most popular poem, one that has been chosen as the nation’s favourite (UK).

Papers consulted

‘The Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family: Snapshots from the Archive’ – Keri Davies (Literature Compass 3/6 2006)

A very useful and clear account of the Moravians and the Blake family.

‘Young William Blake and the Moravian Tradition of Visionary Art’ – Marsha Keith Schuchard (Blake – An Illustrated Quarterly Vol 40, Issue 3, Winter 2006-7)

A fascinating study of Moravian practices, including those of Count Zinzendorf

‘The Influence of the Moravian Collection of Hymns on William Blake’s Later Mythology’ – Wayne C. Ripley (Huntingdon Library Quarterly, vol. 80, Autumn 2017)

This is a detailed study of hymns and Blake’s terminology, more than is needed for general understanding, but probably very useful for those who want to analyse the poetry closely.

‘Anglo-German Connections in William Blake, Johann Georg Hamman, and the Moravians’ – Alexander Regier (SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900,Vol 56, no 4, Autumn 2016

Closely examines the influence of German connections on the English Moravians, and the way that Moravian spiritual thinking and hymnody could have influenced Blake.

‘The Moravian Origins of Kierkegaard’s and Blake’s Socratic Literature’ – James Rovira (Chapter in Kierkegaard, Literature and the Arts, ed Eric Ziolkowski, Northwestern University Press 2018, via JStor) Draws the threads between their Moravian connections and their literature and philosophy.

Books

William Blake’s Sexual Path to Spiritual Vision Marsha Keith Schuchard (Inner Traditions, 2008)

Blake – Peter Ackroyd (Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995) – A biography

William Blake – Tate Catalogue 2019

Videos about the history and style of FrakturSchrift can be found here and here

You may also be interested in some of my earlier posts: