I am always curious about people’s lives from earlier times. While other people buy vintage postcards for their pictures, I buy them to read what’s written on the back. And if I come across old books or objects which have names or clues attached to them, I’m tempted to follow the lead further, since with a little research and a dose of luck, it may be possible to bring their stories back to life. When I was writing my book Growing Your Family Tree, I decided I’d like to test this out by taking on a project to illustrate the way that these kinds of inanimate objects can connect us with past lives. I chose two items which I’ve had for years, but which never investigated before.

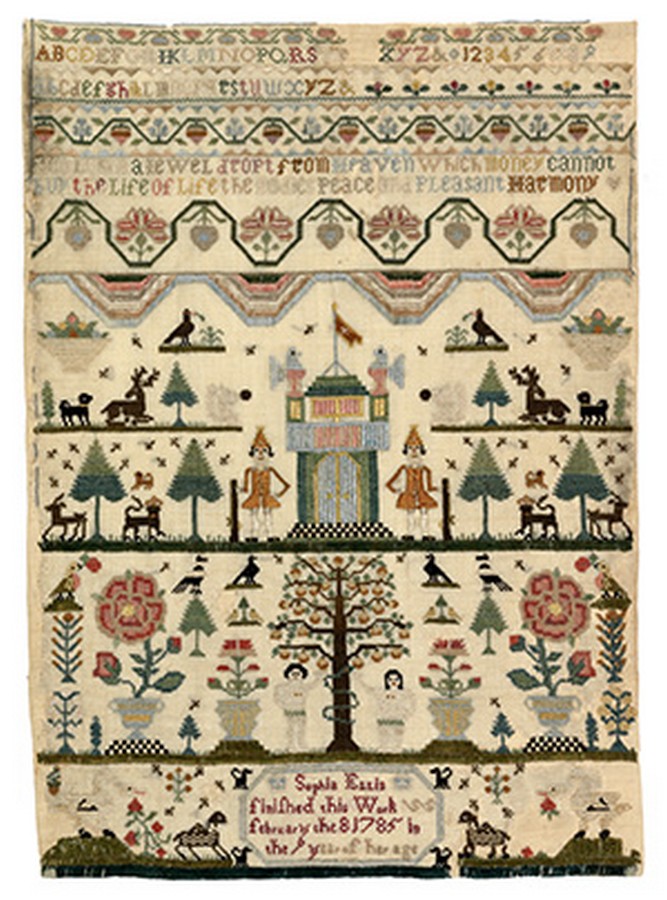

My mother passed on to me two antique needlework samplers, made by little girls of eight and nine years old. Previously, I had simply admired their neat stitching – the letters of the alphabet, flowers, birds and trees set out in tidy symmetry. But now, perhaps I could learn more: who were these children? What kind of a life did they lead?

The account that follows here is a version of what I included in my book (Chapter Eight – Other Lives, Other Stories) but re-written for Cherry’s Cache, with a little extra research added, and of course the chance to add images.

The background to the samplers

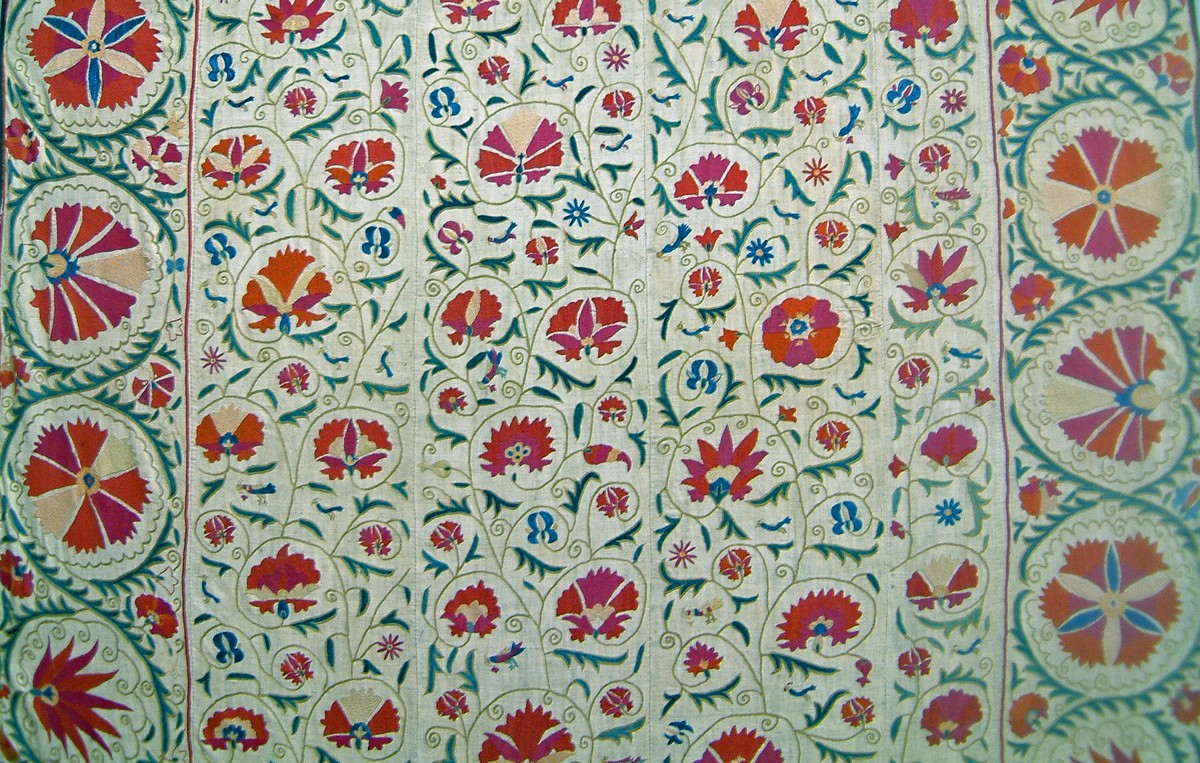

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, very young girls often created decorative samplers as a way of practising their stitching and embroidery. These were usually cloth panels sewn in silks or wools, often with a mixture of flowers and birds, letters and numbers, and even houses and human figures. Sometimes poems, proverbs and prayers were embroidered too, and the girl’s name and age stitched too, along with a date and place. Sewing this type of sampler, with personal details included, was practised mainly in Britain and America. The samplers were often made at school, as part of the curriculum. They were mostly colourful, but those stitched in orphanages, or by Quakers, for instance, tend to be more sober in appearance.

Rebecca Wensor

My first sampler was stitched by Rebecca Wensor, aged eight years, in 1828. To show how I went about tracing her, I’ll include here a few details of the path that I took. Rebecca was born before the start of official registration of births in 1837, but as she would only have been twenty-one at the time of the first census record available (1841), I thought that there would be a good chance that she was still unmarried, and that I might catch her under the same surname. Wensor is an unusual name, which could have given me a head start. But I quickly realised that it could be an alternate spelling of Winsor, a more common name. However, I reckoned that the little girl would most likely have spelled her name in the sampler in the way that the family usually did, as opposed to the census enumerator who might have simply jotted it down as he heard it. A child who spent months labouring over a sampler would want it to be her best work, and would take care to get her name right. But neither version of her surname – Wensor or Winsor – came up with viable results to start with.

However, by checking the name Wensor on its own, I found a few entries for Lincolnshire, including the Bourne area. My parents had lived for a while in the little town of Bourne after they got married, and that my mother had told me that this was where she had bought the sampler. So, with a sense of the path opening up in front of me, I pursued the Wensors of Lincolnshire. One couple, Samuel and Mary Wensor, farmers of Deeping Fen, looked about the right age to be Rebecca’s parents. Although farmers were not necessarily wealthy in those days, it struck me that a farmer’s daughter might be sent to a modest kind of school, where she would learn her letters and arithmetic, and embroider a sampler. Indeed, in nearby New Sleaford in 1841, a pupil called Eliza Wensor is listed as boarding at a little school run by one Mary Smith; at age twelve, she could perhaps have been a younger sister or cousin of Rebecca.

But then came an unwelcome discovery. I couldn’t find any records in the official registry for the marriage or a death of a Rebecca Wensor or Winsor, born around 1820. But in a collection of parish records posted on the internet, I did find the death of a Rebecca Winsor, aged 11 in 1831. She was buried at Deeping St James in Lincolnshire.

The age and the location fitted, and judging by the scarcity of anyone else bearing the same name, I think my little embroiderer probably died three years after sewing her sampler. So although the trail didn’t lead far, I now surmise that Rebecca was most probably the daughter of a Lincolnshire farming family, living in the flat fenland country, and that she received some sort of basic education. I have also found a Wensor Farm on the map, (listed too as Wensor Castle Farm) close to Deeping St James, which could well be that of her family or her relatives. This is a poignant conclusion to her story, but she is not forgotten, and her sampler is still treasured nearly two hundred years later.

Amey Ross

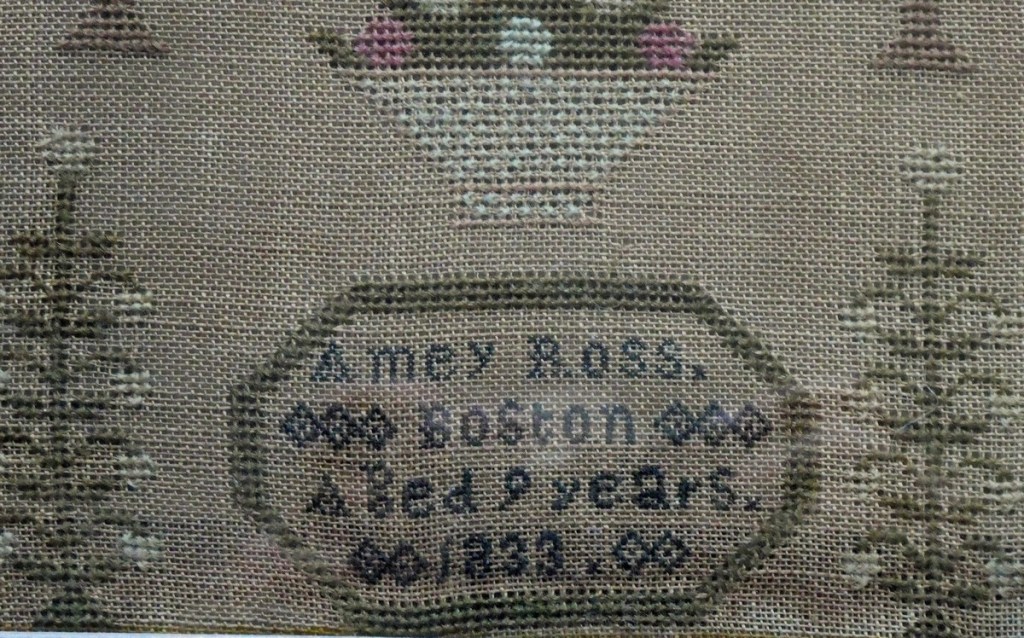

My second sampler announces proudly that it was stitched by Amey Ross, Boston, aged nine years, in 1833. Amey made her sampler square and bold, with two handsome trees flanking flowers and baskets of fruit, setting out her letters and numbers at the top, and her name carefully stitched in a slightly wobbly octagonal frame at the bottom. It’s fortunate for my search that she left such a valuable clue by including the name of the place in which she lived. Boston, Lincolnshire is also within the area where my mother bought some of her first antiques, so probably both samplers found their way on to the local market stalls after house clearances.

Amey was born a little later than Rebecca, in 1824, and the closer dates creep towards 1837 and the first official BMD records, and towards 1841 for the first full census, the more likely we are to find results. Again, it might have seemed at first that she didn’t know how to spell the name Amy correctly but, for the same reasons that I researched Wensor rather than Winsor, I decided to give her the benefit of the doubt. Although neither the 1841 nor the 1851census gave any sign of an Amey or an Amy Ross of the right age, both showed an Amey Ross who was born in about 1801. Obviously, this was not Amey herself, but the unusual spelling suggested that it could be a family name, perhaps Amey’s mother or aunt. And this Amey, a widow, is recorded as living in Skirbeck with her daughter Hannah in the Boston area of Lincolnshire, which is the right location for ‘my’ Amey. In 1851, she is described as a laundress, and her birthplace as Ely in Cambridgeshire.

As for young Amey in 1841, the most likely entry which I found, was for an Anne or Anna Ross, working as a servant in the rectory at Wyberton, close to Boston. But in 1848 there was a fully accurate name for the marriage record of an Amey Ross in Boston. I sent off for it and waited eagerly to see what it would say.

The search was at a crossroads; without travelling to Lincolnshire to look at old parish registers for myself, which weren’t at that time on line, it would have been difficult to go further.

But the certificate arrived, and the information it contained launched my little embroiderer into the next stage of her life. On 9 November 1848, Amey Ross married Allen Reynolds in the parish church of Skirbeck, Lincolnshire. Witnesses were Hannah Ross and Daniel Lote, thus making it even more likely that the Hannah from the census is Amey’s sister. Amey’s father was cited as William Ross, a gardener. Allen’s father was named as Charles Reynolds, farmer.

This made things a little spooky: Charles Reynolds was also the name of my 2 x great-grandfather who came from East Yorkshire, just across the mouth of the Humber from Lincolnshire. I experienced a strange sense of connection, though logically I knew it was very unlikely that they were one and the same. Better, I decided, not to get too side-tracked by the Reynolds issue.

Allen Reynolds was born about 1820 in Frithville, Lincolnshire, and his occupation was that of a miller. He and Amey set up home in Spalding, where they lived for the whole of their married life. I traced them through the census from 1851 to 1881, as they moved only from Deeping Road to Holbeach Road. Spalding is known as ‘the Heart of the Fens’, and is in the South Holland district which is famous for its flowers and produce, grown in its flat, silty soil. There were also plenty of windmills, which would have provided the power to grind the grain, as was Allen’s trade.

Over time, Allen became a master baker too, and took on apprentices. In 1871, Amey’s mother, the older Amey Ross, came to live with them, but had almost certainly died by 1881, by which time there was a niece called Amy Rogers (no ‘e’ in her name) living with them as ‘servant to uncle’! What is significant is that there are no signs on any of the census records of children born to Amey and Allen.

Then came one of those extraordinary moments when the view shifts from official listings to a first-hand, eye-witness account of the Reynolds couple. Through an internet search I found an extract taken from a nineteenth-century memoir called The Jottings of Isaac Elsom, which says:

On July, 1856, death first entered the family of the Elsoms of Spalding, for on that day, Eliza, the eldest child, who was eighteen days short of eight years of age, passed into the Spirit World like a ripe old Christian! Her body was carried in its coffin to the cemetery in the spring cart of Mr. Allen Reynolds, miller and baker of Holbeach Road, Spalding, a dear friend of the family; in whose cart, one time or another, all the members of the Elsom family had many a happy ride! Mr. & Mrs. Reynolds had no children of their own, but seemed to find pleasure in numerous and various acts to members of our family, as long as they lived. The writer has much satisfaction in recording this fact.

This caused my heart to leap! Here is Amey Reynolds as a real person, as a neighbourly woman, friendly to children, and happy to offer them rides in her husband’s delivery cart. Perhaps she loved children all the more, having none of her own. And we can imagine her grief at seeing the cart take away the sad little coffin holding the almost eight-year-old Eliza, whom she may have known since birth. A family history website adds the detail about Eliza that ‘Her mother believed that her death was hastened by having been allowed to walk home from Surfleet during a downpour of rain.’

Allen died in 1886, aged sixty-six, and Amey in 1890, at the same age. I wonder if she had kept her childhood sampler, or if it had already strayed into someone else’s possession? At any rate, I will pass on her story to my own children and grandchildren, and hope that they will keep it with her sampler.

I did my research in 2010, a little ahead of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, which in 2017 put on a special exhibition of ‘Sampled Lives’, showing samplers and the history of the girls who made them.

‘Showcasing over 100 samplers from the Museum’s excellent but often unseen collection, this display highlights the importance of samplers as documentary evidence of past lives (and)…the individuality of each sampler, which in some cases is the only surviving document to record the existence of an ordinary young woman.’

Other objects awaiting the same story-telling are my christening mugs, a collection I picked up cheaply at an auction house, plus one that has come down through my father’s family. I’ve discovered a fair amount already – one little boy became a highly respectable, philanthropic brewer – but there’s work still to be done, finding out who they were.

Related books by Cherry Gilchrist

You may also be interested in a previous blog

Other references:

Samplers, Rebecca Scott (Shire Publications 2009) – An illustrated history and description of embroidered samplers