As those of us in the Northern Hemisphere progress through the darkest days of the year, we may perhaps find ourselves more affected by the power of poetry. Words resonate when we’re not so distracted by bright light and busy lives outside. And there’s long been a tradition for writers, scholars and mystics to seek inspiration in the middle of the night. The medieval mystical Kabbalistic texts compiled in the book known as the Zohar emphasise that at midnight, God enters the Garden of Eden, and at this point the trees sing, and the angels can be heard. Those seeking ‘a whisper from the school of knowledge’ should arise from their beds at midnight, to pray and study. (We have to assume that they went to bed a lot earlier than we tend to do nowadays!)

An ancient Irish poem is set in just this context, that of a monk writing and studying in the depths of night. It comes from the 9th century, and although the monk was Irish, he was at that time located in a monastery named Reichnau, in what is present-day Austria. At this period, the Irish, especially the monks and scholars, were great travellers, and also often had to move abroad to escape Viking raids in theire homeland.

As the fame of Irish scholarship grew, Irish teachers and thinkers were also invited to join centres of learning at schools established in royal and aristocratic courts and large monasteries, so that by the ninth century, the German monk and scholar, Walafrid Strabo remarked: ‘The Irish nation, with whom the custom of travelling into foreign parts has now become almost second nature’ Book of Kells ‘Future Learn’ course, Trinity College, Dublin

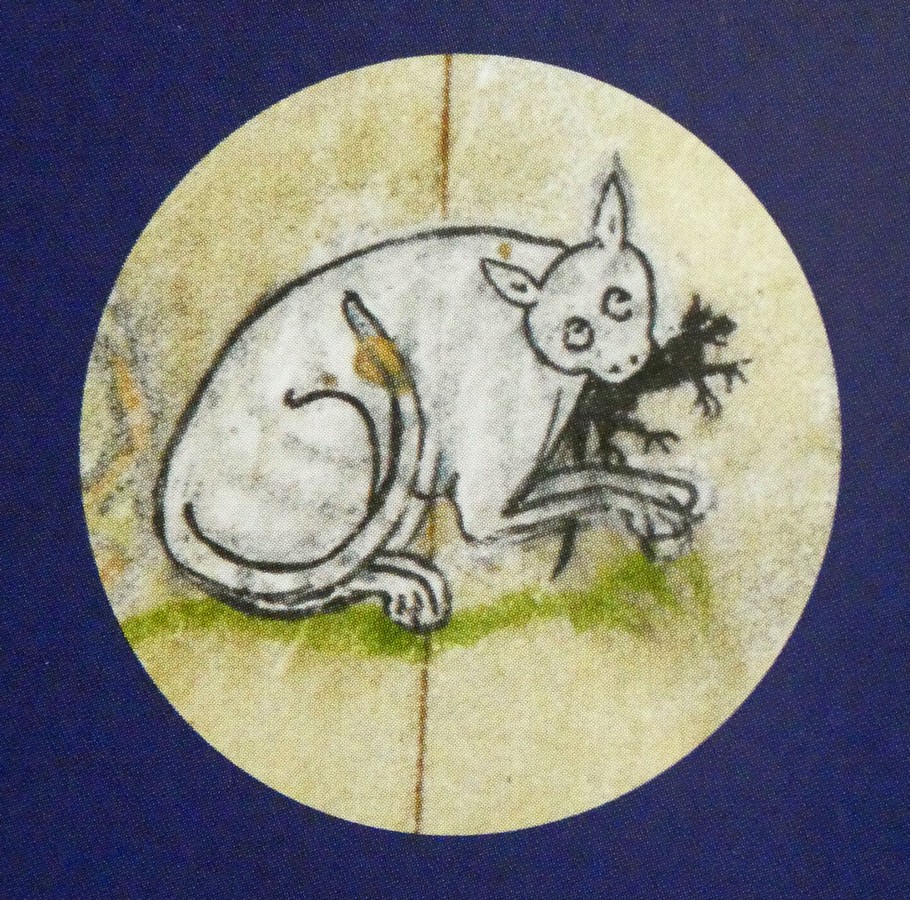

This monk’s notebook shows that he was working on a variety of classical and theological texts, but the poem itself is about his relationship with his cat, Pangur Ban. Both have particular tasks to perform at night; both find their ‘bliss’ in these, whether writing or catching mice. ‘Ban’ means ‘white, and ‘Pangur’ means ‘fuller’, in the sense of part of the process of making and cleaning cloth. So the best guess is that he had a cat with soft white fur. And indeed, a good number of the medieval illustrations of cats show ones which are white in colour.

There were also ginger cats, preferred by the Vikings, often taken on board ship; their descendants are still found around the Mediterranean, and DNA proves their Scandinavian origin. Spotted cats, tabbies, grey and black ones were also prevalent.

Pangur Ban is a touching, intimate poem that astonished me when I came across it a few years ago, and this small miracle still tugs at my heart strings. I’m guessing the anonymous monk would be astonished too, to see how much his verses are valued over a thousand years later. W. H. Auden and Seamus Heaney have both produced striking translations from the Irish, and Samuel Barber has set it to music (see link below). But I prefer this simple, poignant version by Robin Flower.

The scholar and his cat, Pangur Bán I and Pangur Ban my cat, 'Tis a like task we are at: Hunting mice is his delight, Hunting words I sit all night. Better far than praise of men 'Tis to sit with book and pen; Pangur bears me no ill-will, He too plies his simple skill. 'Tis a merry task to see At our tasks how glad are we, When at home we sit and find Entertainment to our mind. Oftentimes a mouse will stray In the hero Pangur's way; Oftentimes my keen thought set Takes a meaning in its net. 'Gainst the wall he sets his eye Full and fierce and sharp and sly; 'Gainst the wall of knowledge I All my little wisdom try. When a mouse darts from its den, O how glad is Pangur then! O what gladness do I prove When I solve the doubts I love! So in peace our task we ply, Pangur Ban, my cat, and I; In our arts we find our bliss, I have mine and he has his. Practice every day has made Pangur perfect in his trade; I get wisdom day and night Turning darkness into light.

You can hear the first verse spoken in the ancient Irish in this recording.

And the Samuel Barber song, titled ‘The Monk and his Cat’, is performed beautifully here by Barbara Bonney.

Cats in ancient Ireland

I first met Pangur Ban and became hooked on Old Irish Cats in a ‘Future Learn’ course on the Book of Kells, which is kept at Trinity College, Dublin. (You can read the relevant section and it’s free to join the rolling course.) . Here I learned that cats were valued in early medieval Ireland, not just as treasured companions, but as useful members of the household. They were accorded legal status:

‘Domestic cats were a high-status possession, owned principally by the elite. Such was their value, that there was an entire set of laws, the Catslechtae (‘cat-sections’) outlining the fines attached to the stealing, injuring or killing a person’s cat. Penalties differed according to the talents of the cat in question. For example, a cat was worth three cows if able to purr and keep its owner’s house, grain store and kiln free of mice, but only half that if was just good at purring.’

This is a description of some of the categories of cat enshrined in old Irish law:

Ameone is ‘a mighty cat that mews’.

Aicrúipnei is also a ‘mighty cat’. but ‘by virtue of its paw’. Ie, a good swiper of rodents. It is ‘a cat of barn and mill and drying-kiln, which is guarding all three’.

Breonei is a female cat who purrs and protects – or may utter ‘an inarticulate cry’, and her value is greater if her purring is loud.

Meone is ‘a pantry cat’, catching mice and rats which might steal the food. Her value seems high at two cows, if she’s good at her job. Otherwise, one cow.

Abaircne is said to be ‘a cat for women’, ‘a strong one brought from the ship of Bresal Brecc in which are white-breasted black cats.’

Folum ‘is a cat who herds, who is kept with the cows in the enclosure.’

Last but not least, we have Rincne, ‘a children’s cat’, thus described because ‘it torments the small children, or the children torment it.’

Medieval Cats

Cats were also appreciated in mainland Britain, and it’s known that a number of monks and ‘anchoresses’ (a type of female hermit) were sometimes permitted to have a cat as a companion. There were also stern warnings that they should not get too attached to the animal! (I am sure that this was ignored, even if an appearance of indifference was kept up.) Although there were some very cruel customs in earlier society involving cats, which I won’t go into here, it’s clear that in general, cats were not only useful members of the household in catching rats and mice, but provided companionship and solace to their human keepers.

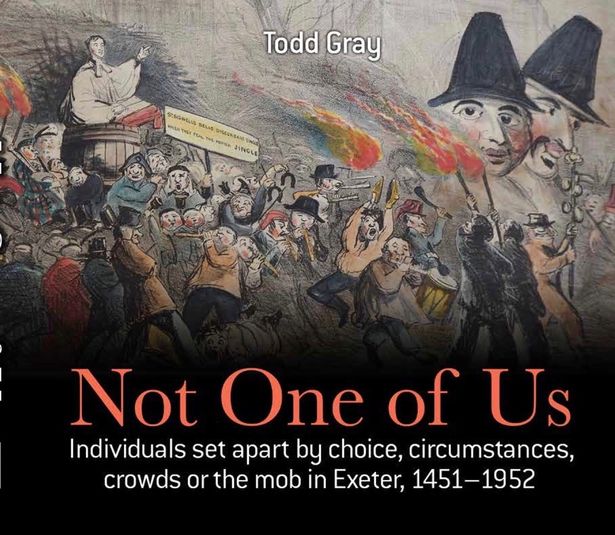

Just occasionally, cats were paid a salary! In Exeter Cathedral today, one of the most popular features for visitors to spy is the medieval cat hole, as you can see below. This is in the door leading to the works of the famous astronomical clock; its ropes would have been greased, and the grease would have attracted vermin. Hence it was important that the Cathedral Cat should be able to hunt them down inside the clock chamber. Cathedral records show that from 1305 – 1467 the cat and its keeper received payment of around a penny a week, chiefly to provide good food for the cat.

Returning to the poem, and my theme of darkness in current posts, it’s definitely one for our midwinter nights. And it reveals that the writer and the hunter are not so far apart:

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

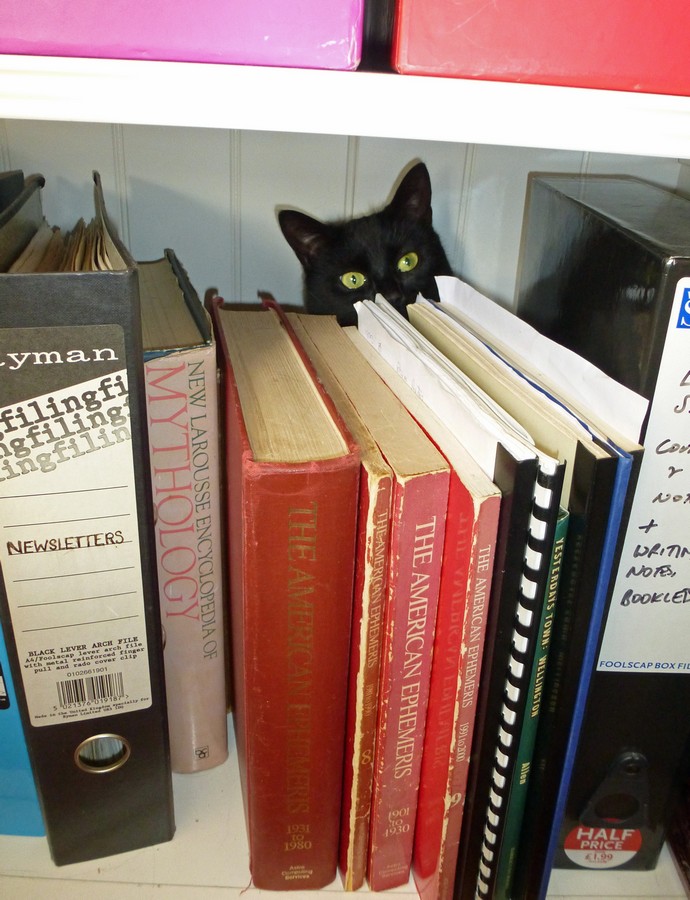

So, Pangur Ban – and in my case Zaq and Cassie – we each have our tasks to perform, and I will try to accept the next live mouse that you deposit at my feet. As you can see, my cats take a lively interest in my work.

Illustrations

All the medieval illustrations in this post are taken from Cats in Medieval Manuscripts by Kathleen Walker-Meikle (British Library, 2011)

(Fair use claim: I purchased a new copy of this delightful book, and use the images with the intention of encouraging others to acquire it.)

Photographs of Exeter Cathedral © Cherry Gilchrist

You may also be interested in reading about the cats of Topsham in Hidden Topsham Part Three

December 28th – A note to everyone: There’s been a marvellous response to this post – thank you all so much for reading this! Comments have been coming in, and are welcome, but please bear in mind that I have to read and ‘approve’ these first, if you are new to this site, so it can take a few hours.