Full twenty years and more are passed Since I left Brummagem. But I set out for home at last To good old Brummagem.

But ev’ry place is altered so Now there’s hardly a place I know Which fills my heart with grief and woe For I can’t find Brummagem.

As I was walking down the street As used to be in Brummagem, I knowed nobody I did meet For they’ve changed their face in Brummagem

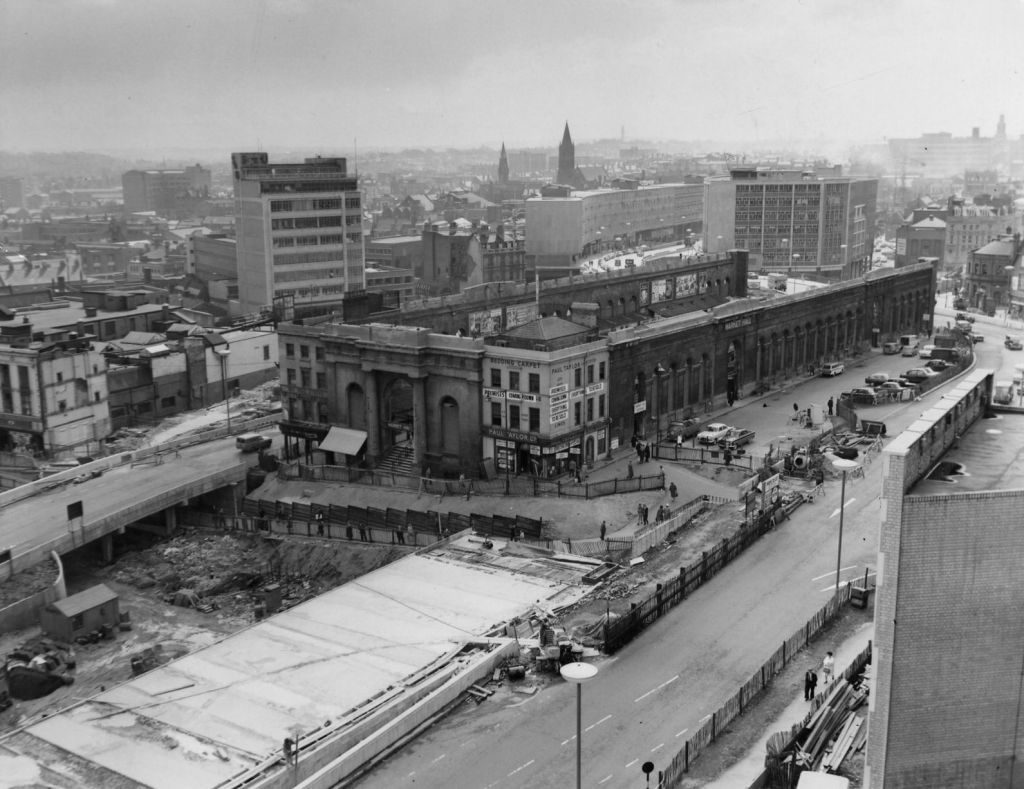

I am here in Birmingham, as bewildered as the poet James Dobbs when he penned this song in the late 18th century. I’ve arrived at New Street Station, and need to find my hotel, which should be only five minutes’ walk from here. But where are the landmarks to guide me? There’s a 1967 map emblazoned in my brain, and in November 2017, this doesn’t serve me well. The station itself has gone through at least two major changes in my time: the first transformation was from the imposing Victorian Temple of the Train, to the brutalist concrete sprawl of the 1960s. And now it is a Temple of Shopping and Bling, titled Grand Central. I emerge from the dingy, low-ceilinged platforms, much as they were in the ‘60s, to acres of glass and chrome, hosting fancy shop fronts and eateries. Here, swarms of cool young people are giving the place a lively vibe. I exit blindly, choosing a way out at random, and emerge into the hustle of rush hour streets and roads.

So, the Canalside Premier Inn is about quarter of a mile away, but I don’t know how I’m going to get there on foot. I’ve done my homework. I have a printout of the area, a 79p app map of Birmingham, and the phone’s satnav to help me. But I’d be better off with a 3D model as the route involves negotiating underpasses, several floors of the Mailbox shopping development, a pedestrian footway and a couple of canals. It has a weird, dream-like quality. I come unstuck quite early on, and find myself heading the wrong way up the inner Ring Road. A cheerful Brummie lady rescues me (most Brummies are cheerful). ‘You want to go back the way you came,’ she tells me firmly. She knows how to decipher the path through the jungle.

When I get to the sign for Navigation Street, there’s a flash of recognition.

“Oh yes, this is where I used to get off the bus from school.”

A few more steps, though, and the recognition dissolves as I face a meaningless stretch of roadway, shops and buildings. I try to re-impose my original map onto the unknown landscape ahead of me – I want to blot out the acres of chrome and concrete and find the turning that once led to the scruffy Greyhound pub, famous for its dubious cider. I remember small children sitting disconsolately on the pavement, waiting for their parents to emerge. It would help to orientate me, perhaps? But the new Navigation Street refuses to budge. Then another memory swims to the surface, mythic and incongruous. Here, one hot afternoon after school, I witnessed a man ride down Navigation Street on a small white pony and hitch it up to a newly-installed parking meter, as though this was the most normal thing in the world to do. I never saw a horse in the centre of Birmingham before or since.

Eventually, I get to the hotel. My room is on the fourth floor, with small windows which squint down onto the tow path of the canal for which the hotel is named. Lights are twinkling in the early evening dusk, as people stroll and jog along the water’s edge. It looks so inviting. I want to join them. But how do I get from the front door of the hotel onto the tow path at the back? It’s not a simple matter. Water, paths, roads and railways combine in a multi-imensional labyrinth. Wandering lost, I at last solve the mystery when I realise that the road I’m using is actually running under the canal. Oh! Of course, now I remember. The majestic, rather gloomy, iron bridge that stretches above me, carries the waterway itself.

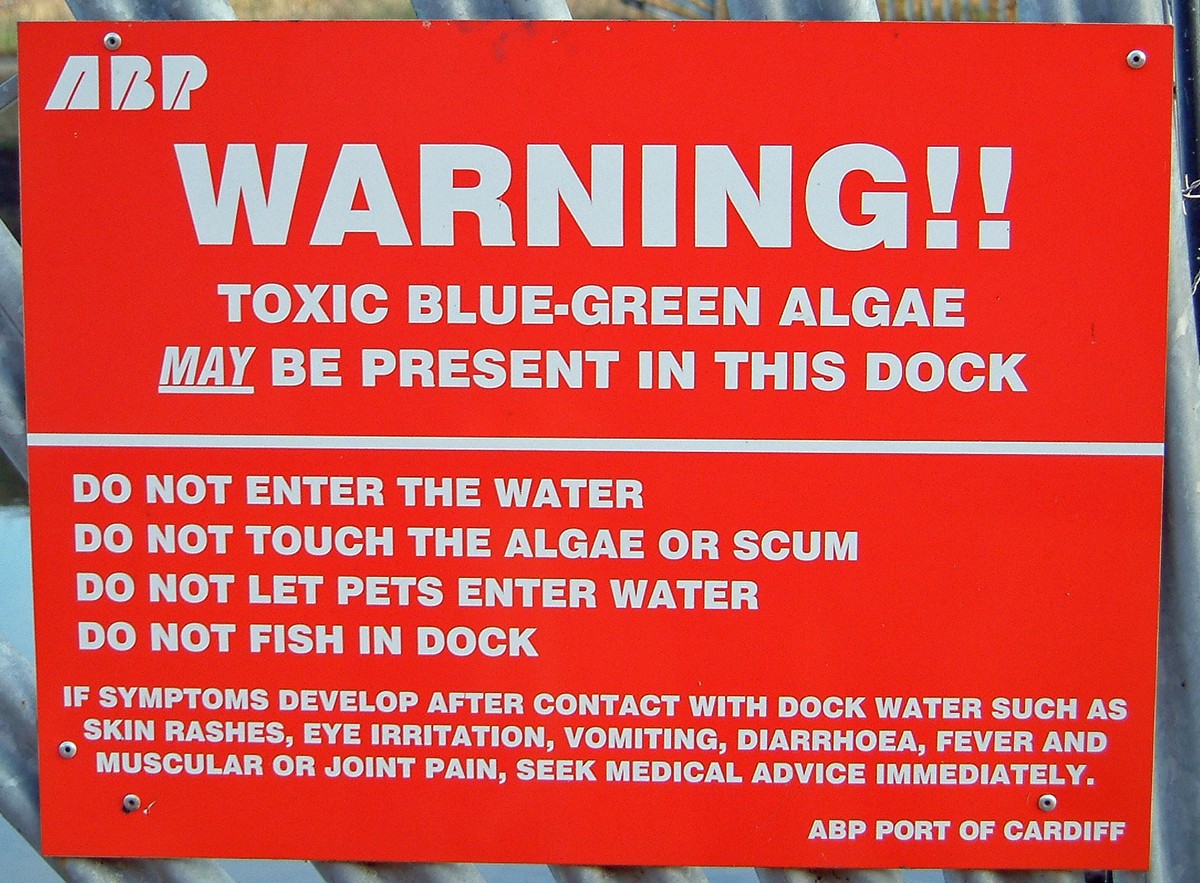

When I do manage to access the tow path, it is a delight. Birmingham has reclaimed its city centre canals and they form a charming network of locks, warehouses, pubs, and iron bridges that sometimes lead onto strange little islands. One even has a signpost, as if for a junction of country lanes. There are colourful narrow boats, tubs of flowers and a country feel to some of the old pubs on the waterside. In the 1960s, by contrast, the canals were neglected, having sunk to their nadir after the glory days of commercial water transport. Back then, the Gas Street Canal Basin where I am now walking, was inhabited mostly by a few beatniks living on dilapidated barges. Most of the canals were either drained hollow, or filled with sludge-green, stagnant water. Once, as an over-confident schoolgirl trying to explore alone, I found myself walking through a long, silent tunnel that seemed like the entrance to Hades. I knew that one of the main city streets was passing above, but I could hear or see absolutely nothing of it. Eerie!

During the next couple of days, which were interspersed with a school reunion and meet-ups with friends, I explored the new Brummagem. I sifted older memories too. My family arrived in the Birmingham area in the late 1950s. But I was too young to head into town on my own, and had very little experience of being in the centre until 1960, when I had to trek across the city every day to my new school. As I got older, I roamed quite freely with my friends around the city centre –it was our territory, and I prided myself on being at ease there.

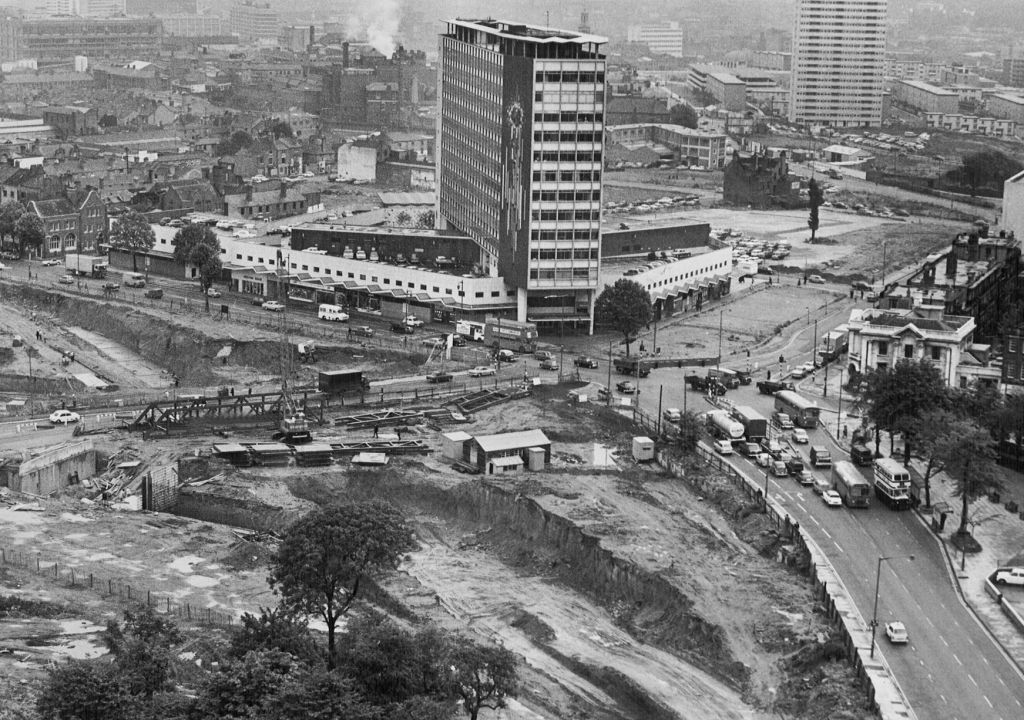

Already the city was undergoing major redevelopment. The craze for modernising meant demolishing splendid old municipal buildings, pubs of character and independent shops with ornate tiled frontages. Many Victorian houses and back-to-back terraces also came in for demolition. From the top of the double-decker bus, as I travelled to and from school, I could see newly-razed areas, zones where houses had stood perhaps as recently as the day before, perhaps even that very morning. Half-broken walls thrust up from piles of rubble, whole streets gone in the blink of an eye, the crash of a wrecking ball. Children quickly took over these abandoned sites, turning them into playgrounds with skipping ropes, footballs and home-made go-carts.

Our bus was often diverted down narrow back streets, where houses were still awaiting the moment of execution. One image imprinted in my memory is the end wall of a house, painted black with the slogan “God Bless Our Boys” in giant white letters. (This, according to internet posts, was in Guildford Street.) It seemed historic to me even then, before my lifetime. For the post-war generation, the war was another country, and we didn’t intend to let it impinge now, when the tide was rising towards the Beatles and miniskirts. We were preparing to surf the wave.

Change was also taking place in the very heart of the city. When we first arrived in 1957, the Bull Ring market was just about still in use. I vaguely recall an old-fashioned outdoor market with a wide and sometimes weird variety of stalls. A classmate bought a grass snake there as a pet. The market survived longer than the snake, until about 1962, when it was cleared away for the Bull Ring shopping centre. This brave new world included the most famous Birmingham landmark of the day: the Rotunda, completed in 1965. It was always controversial as a building; some thought its concrete cylinder a marvel of construction, stretching up to giddy heights, whereas others derided it. However, opposition was fierce when the council proposed to demolish it in the 1980s, and it has since been refurbished. The Bull Ring itself was never an exciting destination; drab tunnels, over-priced cafes and mediocre shops held little of interest for my friends and I as teenagers on limited pocket money. One exception was the recording booth. You sang, spoke or shrieked into the microphone and a few minutes later a 45rpm disk popped out. Was it worth the money? Worth a try – your talent might be ‘discovered’ this way, we thought naively.

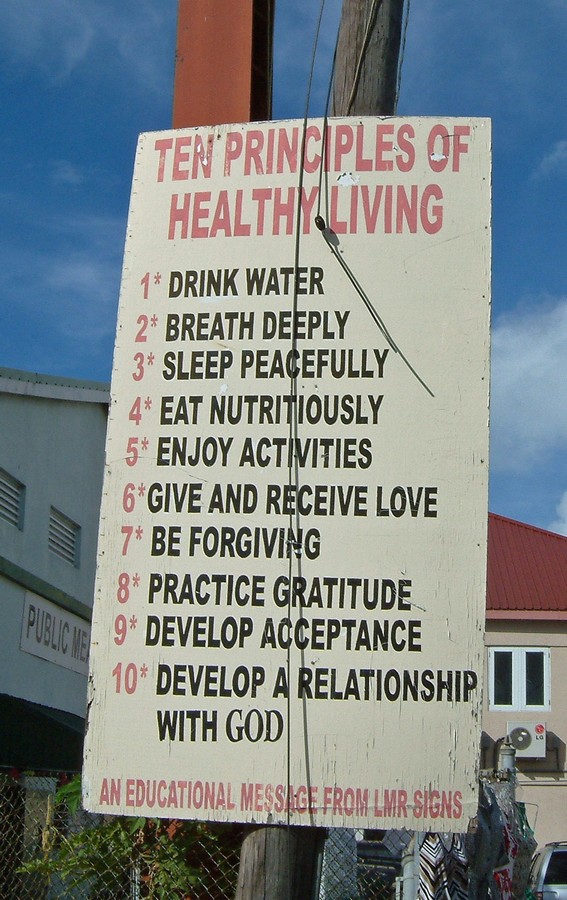

The last courtyard of back-to-backs in central Birmingham has survived thanks to a Jamaican tailor, who didn’t give up his workshop there, and is now restored, and one of the most popular National Trust visitor attractions in the country. On my second day in the city, I took the tour there with a small group of friends. We learned how people had lived in these tiny houses with no indoor toilets or proper washing facilities. Sometimes they slept crammed top-to-toe in beds to save room for a few lodgers, whose rent helped to eke out the tiny family income. Child mortality was high, and general health was poor. But many residents tried to make their homes cosy, and the courtyard at the back was the place for children to play, women to chat, and for neighbours to help each other out.

I briefly saw something of back-to-back life, when I took a job on the Christmas post during my last year at school. My route took me to an area of back-to-back houses where an envelope would be addressed, say, to Mr Dermot O’Leary, care of Mrs Ethel Brown, back of no 15, in something-or-other Court. I would go through the entry, often known as a ‘jitty’ in Birmingham, and try to find the door in question amid a row of unnumbered front doors facing into the courtyard. Often I had to knock and ask. The courtyards had a romantic feel to me, I have to admit. There was an atmosphere of the cottage, of an old way of life that had made its way into the city.

After leaving school, I lost my sense of orientation during visits to Birmingham. Usually, I didn’t have to figure out where I was going as I was meeting a local friend who shepherded me, or heading to a fixed rendezvous point. But this time, in October 2017, I was spending time on my own during my visit, and my relationship with the city had to be reinvented. And this gave me a chance to see with new eyes.

“What,” I asked one of my old friends, “is that extraordinary building with the golden turban?”

“That,” she said, “is the new library.”

So I visited it later that day. To locals, it’s now a familiar sight, but to me, an uninitiated visitor, the library resembled a Central Asian-style tiered building, covered in patterns of blue and white, enmeshed in a kind of filigree, and topped off with what I will continue to call a golden turban. I found it glorious. Inside, it is still curiously evocative though of the original Birmingham Reference Library, which was much lamented when it was demolished in the late ‘60s. Today’s building is open plan, with gently sloping travellators, but it maintains the quality of a ringed dome, with huge bookcases encircling you as you glide up through the floors through a forest of gently twinkling lights.

On Level 3 there is a spacious roof garden, planted with fruit bushes and herbs, where you can step out and admire the city centre from on high. Below me, I saw another huge demolition-and-reconstruction project in progress. It had greedily devoured the area where the Hall of Memory, a small, circular, neoclassical building, was still just about standing, and its perimeter stretched to the nearby Town Hall, with its fluted pillars. Of course these landmarks are preserved – the city is much more careful now about its heritage – but they will now be minor monuments amidst vast edifices.

Coming away from the city and sifting my impressions, I realised that although I recoiled from this large-scale demolition, the energy of the place had grabbed me. To quote from the guide at the back-to-backs, Birmingham has always been a “chuck it up” kind of city. Pile it high, and make it shiny and colourful. It is the city where everyone can have a go, from the kind of trade you follow, to the way you drive your car (‘cowboy country’ as I’ve always called it, trying to navigate through Spaghetti Junction) to the way you – or the city council on your behalf – has a crack at shaping your surroundings. Birmingham, I’d say, is all for individualism.

And something of the ‘chuck it up’ mood still prevails even in the most prestigious new developments, where buildings are thrown up to look like handfuls of coloured dice, and adorned with crazy mirror work, and strangely angled walls. I’m not usually a fan of new cities, but during my three days, I admired what’s going on here. I felt that Birmingham was and is being true to itself. Big, bold, and still full of bling. It gives you new vistas, and unexpected humour too. ‘How come that man is walking upside down halfway up a building?’ It took a few seconds before I realised that I was seeing a reflection in a distorting wall of mirrors, high up above the pavement.

And there is sensitivity too, among the wholescale changes. One example is the little stream that cascades down the hill from the Bull Ring to St Martin’s Church below. It is a rivulet from a river that is now paved-over, but this little flow of water has been brought up to the surface, and a polished granite wall erected beside it, engraved with a poem about the city. And so history is not completely submerged.

Birmingham is multicultural too on a phenomenal scale. The first wave of immigrants from the Caribbean, India and Pakistan had not long arrived when I came to Birmingham in the late 50s. My parents steered me across the Bull Ring as I marvelled at Indian ladies in gorgeous saris and bare midriffs, shivering in the damp winter air. Now of course there are second and third generations who have been born in Birmingham, and who have made the city their own. It is a youthful place: 40% of Birmingham’s population is under twenty-five, boasts a poster in the city centre.

Shopping remains a Brummie preoccupation, but the old premier shopping streets have been eclipsed by the smart new complexes such as Mailbox and Grand Central. Though I was happy to see the Rag Market still in full swing, on the far side of the Bull Ring. I recalled Corporation Street in its smarter days, where Marshall and Snelgrove’s department store still used bags and hatboxes patterned in a 1940s style (shown below).

Even posher was Rackham’s, where I had a holiday job selling girls’ school knickers. I also had one at Neatawear, where I had to put a hand-written bill and the money into a brass canister that shot up to the cashier’s office in a pneumatic tube. Now Corporation Street and New Street are almost backwaters, and in a way I’m not sorry, because they always seemed stuffy and self-righteous to younger customers. But oh – what happened to the Kardomah, with its chocolate-and-coffee cake? And Yates Wine Lodge, where old ladies tippled their port? (How come I went in there?…memory is blank…)

I ended my astonishing but head-splitting tour of Birmingham back at New Street Station. I had begun there, clutching my luggage in a panic-stricken way, lost in Brummagem just like James Dobbs in the late 18th century. It’s extraordinary to think that I echoed his sentiments nearly 200 years later. But then, perhaps it indicates that Birmingham is still the same. It is still in a state of flux, and ever-expanding to meet the needs of the day. I detect a growing maturity, though, in terms of what is saved and what is lost. The best of the old is now preserved, and the city’s identity celebrated with various sophisticated artistic touches, like the modern sculptures which inhabit Victoria Square, alongside the po-faced statue of Queen Victoria herself, as in the earlier photo. (I once stuck a poster onto her advertising a concert by Ravi Shankar, but that’s another story.) On my journey this time, I couldn’t find exactly what I once knew, but after three days of walking the city, I felt that, yes, I had found Brummagem.

Photos of Birmingham today by Cherry Gilchrist

A version of the song ‘I can’t find Brummagem’ performed by John Wilks can be heard here

Photos of Gas Street Basin in 1968 by Martin Tester.

Photos of the last day of trading in the Bull Ring market by Phyllis Nicklin (1913-1969), who was a University of Birmingham geography teacher. ‘She made these colour slides as lecture aids for her lectures on the geography of Birmingham.’

Photo of Kardomah Café (1965) posted on ‘This is Birmingham’ Facebook page, 20th June 2016

All other 1960s photos of Birmingham from the Birmingham Mail feature ‘This is what Birmingham was like in the 1960s’

Related books by Cherry Gilchrist

Contacts and Comments – I’m delighted to have comments – it may take a little time for these to be checked out and appear on the page. And if you’d like to get in touch with me directly, there is a ‘contact’ link right at the bottom of the page, which will get an email to me promptly. You can also contact me via my author’s website at http://www.cherrygilchrist.co.uk. (This is more reliable than finding me via Messenger).