Family history is a quest, and the act of going out on site visits to do your research can be a story in itself. If you visit the places where your ancestors lived and worked, it can become a magical journey where surprises and discoveries abound. Savouring the atmosphere of ancestral haunts and walking the landscapes where they too walked can bring a kind of knowledge beyond that of hard facts.

In this post, I have written up one of my own quests on the trail of the ancestors – a trip to Coventry to discover more of my 3 x great grandfather, watchmaker Daniel Brown. I wrote it down a few years ago, in such a way that I could share the story with others, but it has never seen the light of day until now. I offer it here, after giving it the cold editorial eye, and a sprucing-up.

For those interested in doing something similar, I’ve added tips and suggestions about the process at the end. It’s worth making a special undertaking to do this. While teaching life writing and family history courses, I’ve often encouraged people to set up a ‘quest’ and write about their discoveries, and it’s always been exciting and moving to read their stories.

Arrival in Spon Street

‘Is this Spon Street?’ asks my husband, in mild disbelief.

We gaze down the narrow city street, studded with a mixture of nightclubs and kebab takeaways, bridalwear shops and ‘the last proper butcher’s in Coventry’. It’s a wet, cold Saturday morning, and the street is deserted. Is this really the historic quarter, the street once filled by hundreds of craftsmen: dyers and weavers, shoemakers and watchmakers? The Coventry websites call it ‘the town’s finest renovation project’, but it seems a little sad right now. The photos they show, a real dream of an ancient street, obviously must depend on where you point the camera. Historical in part, we concede, noticing some exquisite groups of half-timbered houses dotted along the street, among the Victorian and ‘60s infill. We are here to follow up one of those former inhabitants, my 3 x great grandfather, Daniel Brown, watchmaker of Spon Street in the late 18th century. And even though first impressions are not quite as expected, we’re ready to take what the city can offer us.

I was last in Coventry when I was at school in Birmingham. Coventry wasn’t a place you came to then except to see the new cathedral, or, in my case, to listen to the Rolling Stones. It’s not familiar, although I can still recognise the ‘modern’ shopping precinct of the late 1960s where I looked in vain for trendy clothes, now smartened up with a glass roof. We aren’t here to cover my old trails, though, but rather to find new ones. When you’re hunting ancestors, even in a place you know well, you inevitably see your surroundings in a different light, and explore nooks and crannies which wouldn’t have attracted your attention before. Even the air smells different when you’re on the trail; often, a strange magic creeps in, and such days remain glowing in the memory.

So here is the background to this particular quest. Daniel Brown was born around 1768, and lived in the labyrinth of workshops in Spon Street for most of his life, practising his skills as a watchmaker. He married a woman called Anne –surname possibly Fulford – and they produced a family of some five children. One of these children, James, became my 2 x great grandfather. It seems that Daniel’s own father, Isaac, was a weaver, and since James reverted to the weaving trade, Daniel is the only watchmaker in my line, and of great interest as such. What can Coventry tell me about him?

He must have done well at his trade, since at his death at the age of 81 in 1849, he had money and property to leave in his will, an estate worth about £25,000 in today’s terms. Daniel’s first will had me fooled, though: it was a draft prepared less than ten years before his death, written in an almost indecipherable hand. I assumed it was his final will, but when I’d finally transcribed it, I thought it might be prudent to check for a proven will. There was one – much more legible this time, but oh, what had the old so-and-so done? He’d gone and got married again, in 1844, at the age of 76, to one Sarah Stone. Both their ages are coyly concealed on the marriage certificate, which declares simply that they are ‘of full age’. Well, it must have been obvious in Daniel’s case, but I’d like to know if Sarah was a tempting young wench, or a shrewd elderly widow? At any rate, Sarah comes in for the sum of 10 shillings to be paid to her ‘at the end of every week’ until it reaches a total of £300. This surely shows an astuteness in Daniel’s control of his money – if she was a gold digger, she would only be in line for a share of his assets and if she died soon after him, the residue of the bequest would pass back to his own family. Other bequests are to his children and grandchildren, who each receive a decent legacy. All, that is, except for my 2 x gt. grandfather James, who obviously owed his father a packet already, since Daniel’s will offers to write off James’s debts, but little else.

In the city centre itself, we admire Lady Godiva’s statue, a legend which is a tribute to the independence and feistiness of the inhabitants.

Discovering the city

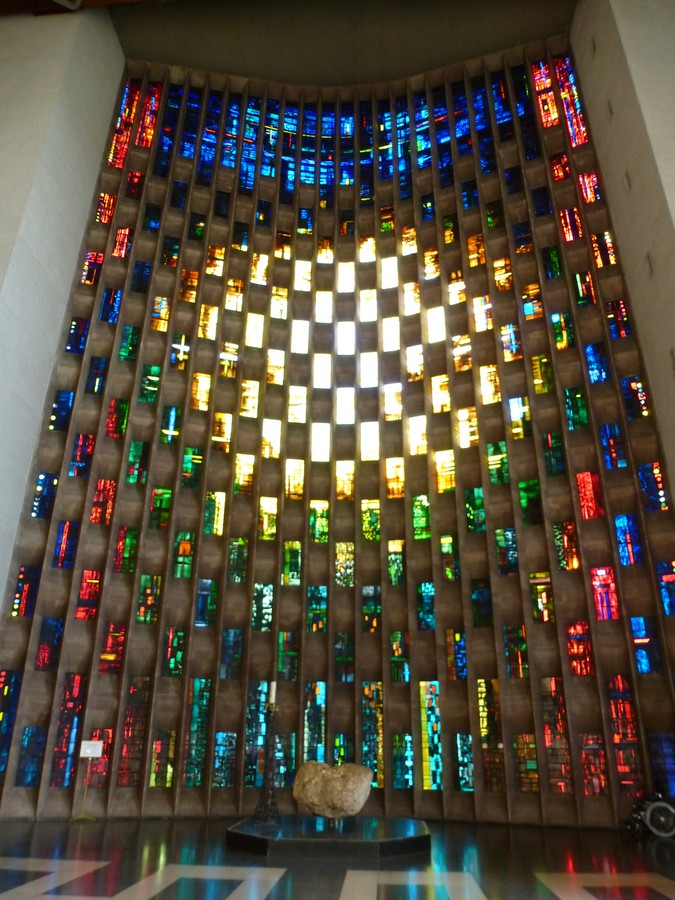

We pay the steep entrance fee into the Cathedral to see not only the famous Graham Sutherland tapestry, but the Piper Baptistry window, the Whistler angels etched on glass, and the Frink choir stalls. The more we gaze, the more I appreciate this incredible building and its art, far more than I did in my restless teenage years. Yet I’m assailed by a sharp sense of the sadness and anger embedded here, in the juxtaposition of the new Cathedral and the ruins of the old, following the horrendous destruction of the Blitz. Witnessing this contrast, though, helps me to get a perspective on the longer history of the city. Although my direct-line descendants moved out to the nearby town of Bedworth, Coventry must still have been imprinted in the family story. My sense of the old Coventry as a productive, busy place, fostering independent craftspeople and small businesses, has now been heightened by the contrast with its post-war trauma. Indeed, almost anything you see and experience on a family history quest is likely to feed your knowledge, and fire up your imagination. You can never achieve this in quite the same way from research carried out at a distance.

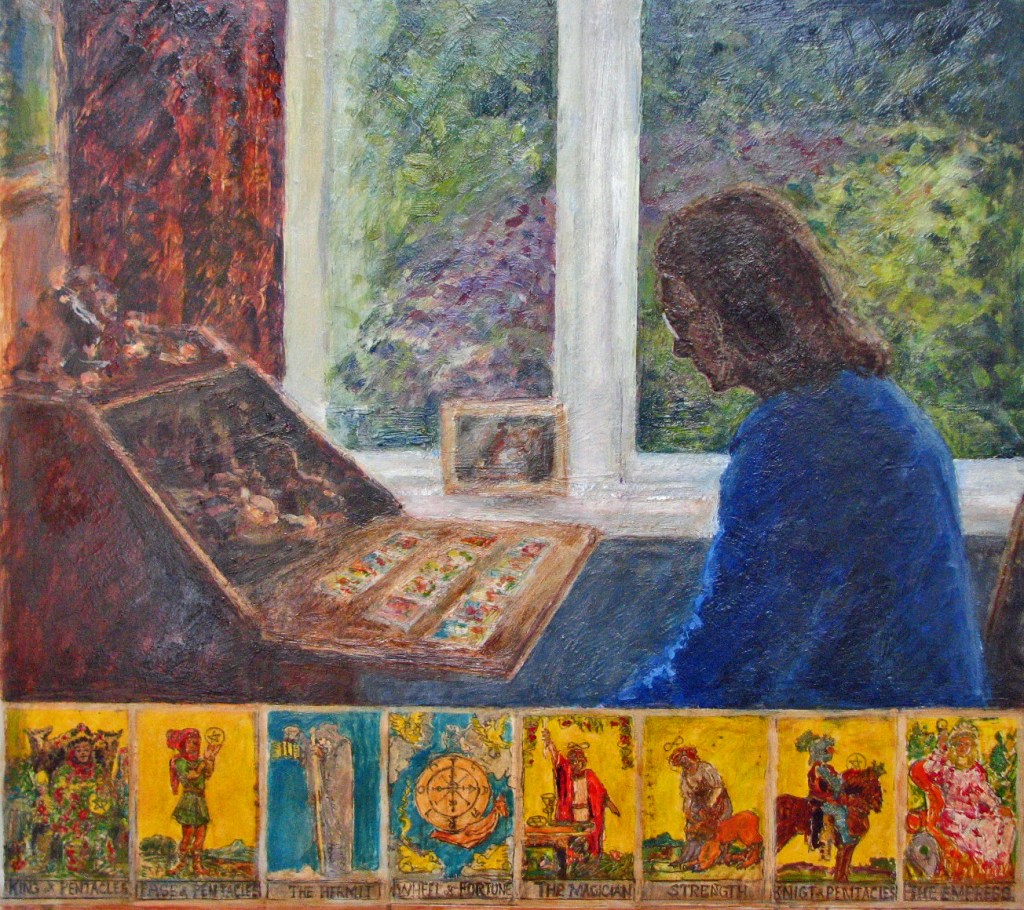

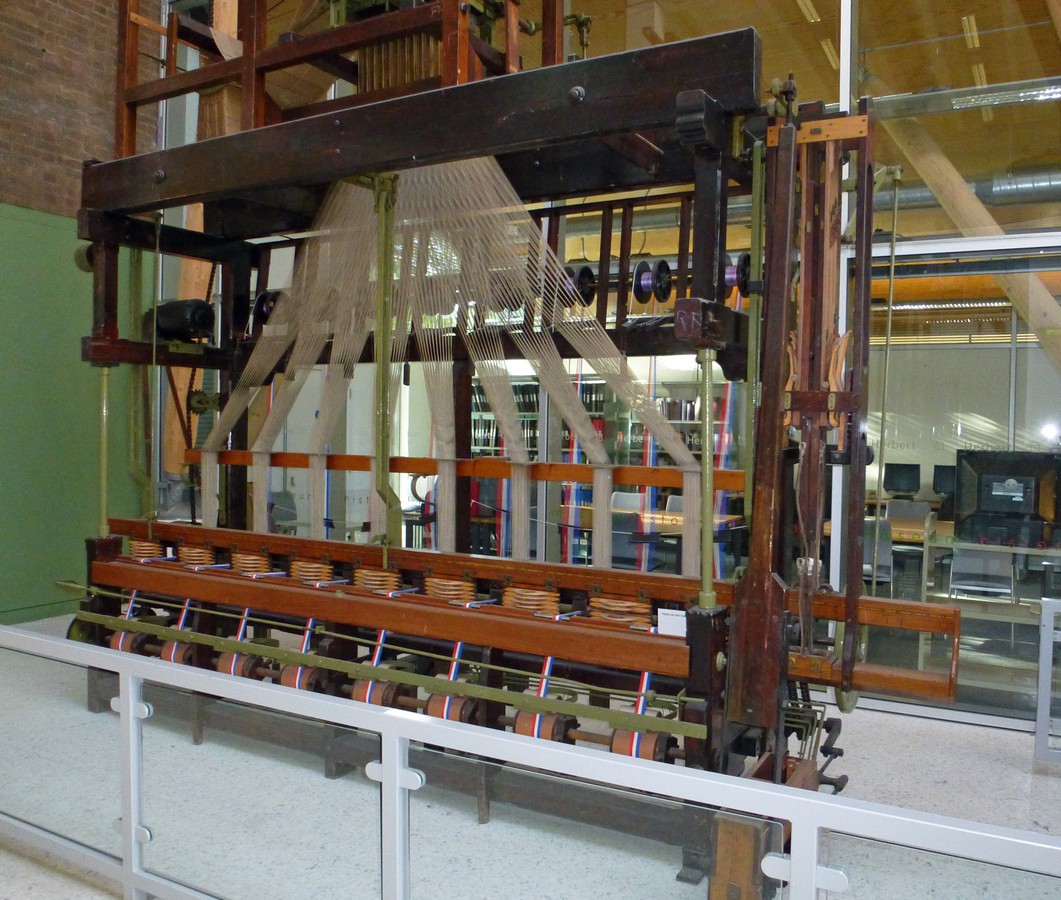

I am eager to visit the ribbon weaving display at the Herbert Museum and City Art Gallery. Many of Daniel’s relatives and descendants, including my great grandmother, worked in this industry, often from as young as ten years old. In the 19th century, beautiful and intricate silk ribbons were woven to adorn ladies’ costumes, and both Coventry and Bedworth depended economically upon this trade. The industry continued through the era of hand loom weaving into that of machine weaving and jacquard looms, which were capable of reproducing complex patterns. The Museum has a stunning example of a jacquard loom, and a video of the monster at work. (You can see below an example of an earlier hand loom on the left, and a jacquard on the right.)

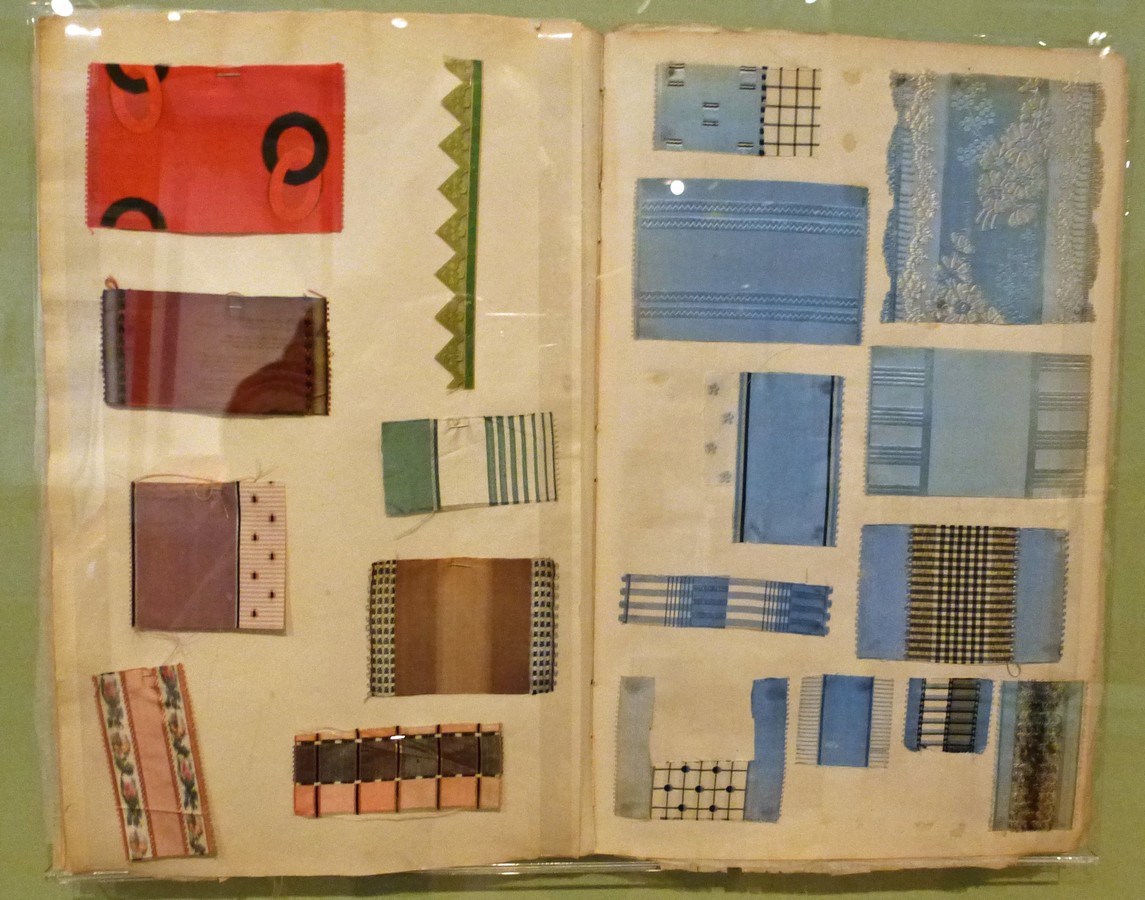

The images below show the types of decorative silk ribbon that were being woven in Coventry and the surrounding areas in the 18th and early 19th centuries. These are in pattern books, preserved at the Herbert Museum.

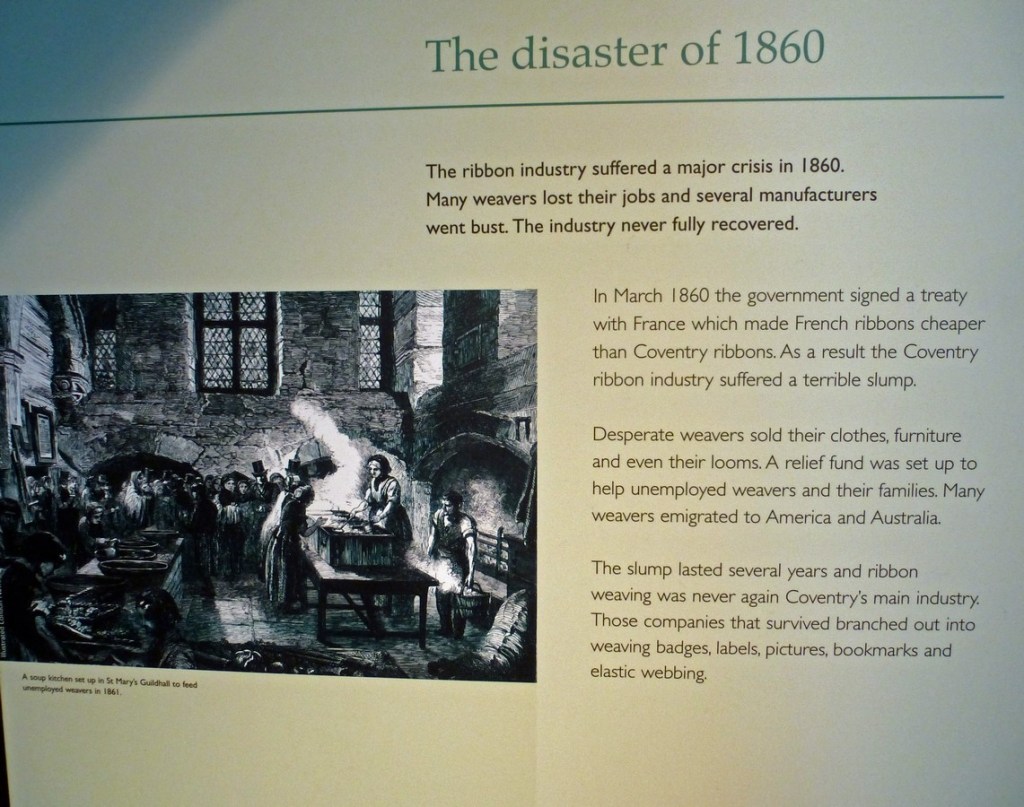

Ribbon weaving was often done from family workshops, sometimes situated on the top floor of their cottages for maximum light, but later subsumed into fully-industrialised factories which swallowed up their children for the workforce. Cash’s (of school nametapes fame) is probably the most famous of these old Coventry firms. At the Tourist Information Office – another source of local wisdom – the woman at the desk told me wryly that most of the Cash’s name tapes are now woven in Turkey, although some decorative bookmarks are still made locally as souvenirs. Now, in the Museum, we admire the sample ribbon pattern books dating from the 1840s, the time when my Bedworth ancestors were in the trade. There’s also an account of the terrible times of hardship that hit the ribbon weavers after the tariffs were lifted on the import of French silk, causing a major slump in home production. Famine struck both Coventry and Bedworth, soup kitchens were set up, and charitable funds were used to send whole families abroad to the Colonies. My great grandfather was fortunate in that he spotted the opportunity to work on the railways, which gave the chance for a family to move, something very difficult at the time. (He ended his career as signalman at Althorp Park Station, known these days as the stately house where Princess Diana lived.)

Winners and Losers

On these quests, not every plan may prove possible. It seems that I can’t make the special visit that I’d been promised earlier, to see the rest of the ribbon weaving samples in store. It’s Saturday, and curators only work Monday to Friday, I’m told. Another time, perhaps. Indeed, I’ve learned from past experience, that it’s more rewarding to stay with what can be done, than to fret about what can’t. Perhaps I can take this enticing option on a future visit.

But, to balance this up, contrary to what the website says, the History Centre is open on Saturdays. An inviting, glass-walled library on the ground floor of the Museum, it is available for any walk-in visitors who’d like to consult shelves of local material, with the assistance of knowledgeable volunteers. We only have a short time, but some quick browsing produces a possible match for Daniel in the apprenticeship records and a plot number for him in the London Road Cemetery. This will at least give us a chance to see his gravestone; I discovered a picture of his memorial stone on a website a couple of nights ago.

We return to Spon Street, which is now looking a little brighter, with a few visitors in its shops and cafes. This was once a major highway into the city, and has been an important part of Coventry’s trading quarter since medieval times. But apart from the recent historic reconstruction at the inner end, little now remains of the cottages and bustling workshops which once flanked it for the best part of a mile. The city ring road has cut through it, and the two parts are severed, and only accessible on foot. The move to the era of ‘Car is God’ has created some truly terrible town planning in the Midlands, as I’ve written about in ‘Finding Brummagem’. The outer stretch is quiet now, leading us past blocks of flats, deserted open grassland, community centres and an occasional old cottage. But the sense of space is opened up, and it’s possible to project the imagination even further back in history, to a time when the area was rural. The river Sherbourne, which the dyers once used, is still racing along behind a row of houses, and on the old stone bridge which crosses it, you can stand and dream of life gone by.

Two o’clock, and we haven’t had lunch yet. (Food is always important on my quests. Fuel is definitely needed.) Oh, and the Watch Museum is open in Spon Street as well. Another piece of good fortune, as it only opens for a few hours twice a week. Can’t miss that. So shall we try the cemetery too? I steal a sideways glance at my husband. He doesn’t look too jaded, so maybe something to eat will strengthen us enough to complete the quest. We go for coffee and sandwiches in a bistro operating in one of the reconstructed 17th century houses, then stroll over to the Watch Museum. This consists of a very decrepit block of cottages, which lead back from the street into a courtyard.

‘Come out to the back!’

A museum guide beckons us eagerly. He throws open the door to one of three privies, lovingly restored. A hundred and eleven people once lived and worked here, and they had to share the facilities.

He scratched his head. ‘Some tourists have borrowed our bowler hats,’ he says, and shows us to where a couple of visitors are posing bowler-hatted for their photos against the back wall of the final cottage, which has a gaping crack running from top to bottom.

The inside rooms on show are incredibly dilapidated too, with flaking, distempered doors and bare floors, but they give me a sense of the old way of life more vividly than an artistic reconstruction. Was Daniel’s life this hard? Did he have to squirrel away his money to improve his lot?

We admire the selection of Coventry watches on display, and I wonder about Daniel’s status. I’ve found him listed in the watchmakers’ records for the town, but I don’t know if he worked entirely on his own account, or as a piece-worker for one of the local firms? I’m told by the guide that watchmakers could do either, or both, but that individual watches were rarely signed as many watches were composite productions. I’ve already seen in my research that the censuses of the period reveal many dial-makers and watch-finishers, as well as watchmakers proper. So finding a ‘Daniel Brown’ watch remains a dream for me.

‘Most watchmakers were apprenticed, and the first thing they got when they’d served the apprenticeship was the sack,’ the guide informs us. ‘They had to make shift for themselves, then. But they were also freer to do what they wanted. Look out for a marriage at around the age of twenty-one. They weren’t allowed to marry before that. It can help you with knowing the age of your ancestor.’

I check my dossier. ‘Twenty-four,’ I say.

He nods sagely. ‘Sounds about right. They tended to marry as soon as they could.’

I buy a booklet produced by the Museum, describing a historic watchmakers’ trail around the city, and then we’re off to our final stop: the London Road Cemetery. We are back in the car, and snarled up on the Coventry Ring Road, which was probably devised by planners when they were in a sadistic mood. Poor old Jane, our Sat Nav voice, can’t cope with all their loops and kinks. We circle around the city in the wrong direction. Eventually, as navigator I tell Robert to take the next road off the demonic ring.

‘Where’s it going?’ he asks.

‘I don’t know. I don’t care. Anywhere is better than this.’

Jane recovers her sanity and coolly directs us to the post code for the cemetery. And that’s where she can help no further. We only have a vague memory of the plan we consulted at the History Centre, with its numbered section and grave. We drive all around it, finally choose one of the unmarked entrances, and drive the car a little way in. It’s late afternoon now, and the place is practically deserted. We wander through the vast graveyard, looking for older stones that will show us we’re in the right area. But only modern graves catch our eye, some vividly decorated with pink flowers and teddies. Who can we ask? There’s one mourner by a grave, but he is truly mourning, wiping away tears. I decide to go through an iron gate in the wall – shades of The Secret Garden – to see if the old area is beyond there. It’s getting dusky, and I hesitate when I see three lads who look as though they might be drug dealing. Ah no, here comes a safe-looking middle-aged couple with their shopping. They tell me, rather vaguely, that there’s another complete section of the cemetery we need to find.

‘Where the Rolls Royce factory was. You know,’ she says helpfully.

‘No, I’m sorry, I don’t,’ I reply. ‘Do you know what road the entrance is on?’

‘No, haven’t a clue,’ answers her husband.

We decide to try again. This time, we find a friendly Irish lady tidying up a grave. She’s driven her car right up to the graveside. ‘Have to be careful. People have been robbed here.’ She tells us that there is a Chapel, and an older graveyard around it. ‘Just up there.’ She waves her hand vaguely.

Thank you, thank you. By now, Robert is using his visual skills as a professional artist and is consulting the photo of the gravestone.

‘Look at the shape of it,’ he says, tracing the indentations and angles cut into the top of the stone. He also has stonemason ancestors, so I’m trusting his instincts to spot the right one.

But we can’t find anything. We ask another man, also Irish as it happens, who shakes his head. As we head towards the exit, we see a very organised-looking lady tending a grave. I say it’s not worth asking, but Robert says we should give it one last shot.

‘Of course,’ she says. ‘You need to go out of here, and then find the other entrance, the original one. It’s just down the road.’

Ah, it’s in a different place altogether! The cemetery was opened in 1847 and since then, the railway line has sliced it in half. We pick up the car which is languishing near a cedar tree, and drive out, round, down – and there it is – the older, grander entrance to the original cemetery. Daniel Brown was one of the first to be buried there in 1849.

Four magpies bounce across the path.

‘A boy!’ we say excitedly, in line with the old children’s rhyme. But will we find our man?

We search the first area without any luck, and I am thinking that it’s nearly time to go home. The air is darker, the mood is eerie, and we’re in a place where the dead are thick in number and the living very scarce. We are the only ones, in fact.

Then we spot the Chapel, further along. It’s a kind of strange, mausoleum type of building and with it comes a whiff of the Victorian cult of death. We move towards it, through the obelisks and the forest of stones, both plain and elaborate, some now leaning at an angle or almost swallowed up by the trees.

‘I’ll take this side, you take the other,’ I suggest.

Five minutes later, Robert calls out: ‘Found it!’

And there he is. ‘Daniel Brown, departed this life June 21st 1849 aged 81 years. And of John Brown, son of the above, who died Dec 5th 1855, aged 58 years.’

‘Hello, grandpa,’ I say softly.

Websites for Coventry history

Cash’s weaving, Coventry

Coventry Watch Museum

Herbert Art Gallery and Museum

Spon Street, Coventry – Coventry Walks website , Historic Coventry

Article on the changing face of Coventry, with photos of historic buildings in Spon End

Tips for a Family History Quest

Planning and carrying out the quest

Plan out your day, but allow for the unexpected as well. Following up new leads is half the fun!

Think about your route in advance, especially if it involves finding car parks in towns. It can save you time and frustration.

It can be more fun and give support to have someone with you, but be up front about the fact that you’ll be focused full-time on following the trail. Don’t plan extra side trips.

Suggestions for what to take

A small dossier of relevant material, eg local information and notes on family records. (Keep it light and compact – it can be difficult to find something quickly from a big sheaf of papers.)

Recording materials, such as a notebook, camera and a voice recorder, which can be on your phone.

A relevant map if possible. Ordinance Survey maps are useful for detailed navigation in the countryside (or the equivalent outside the UK); for a city, you can probably download a visitor’s map from the internet.

While on the trail

Ask for help from locals – anyone from a farmer to a museum attendant may have valuable clues for you. If you tell them you have family connections they may open up, and give you much more detailed information.

Buy local leaflets or booklets, on anything from folklore to churches. If you don’t have time to look at them while you’re on your quest, they may be really useful later. It’s much harder to track them down when out of the area.

Follow your nose – it may be the best guide that you have!

Be philosophical: you may be thwarted on some counts, but find wonderful new avenues to explore too.

Afterwards

Do write up your quest within a few days. If you’re short of time, just make notes, but make them as full as possible. It’s extraordinary how quickly we forget details.

Set yourself a reasonable length to write to – about 1500-5000 words is usually plenty. If you make it much longer, it may be too much of a project and never get completed. It’s better to make the first account precise, and expand it later, if you wish.

There’s always scope for editing! Sometimes the story comes out in a rush, which is great for conveying energy, but be ready to check and prune it later.

Share it with others – it makes a wonderful bulletin to circulate to other family members. Everyone loves to read a story.

Reflect on what questions have arisen out of your quest. You may end up with more questions than answers, but they may stimulate further research, and might even pave the way for the next quest.

You may also be interested in these other family history posts: