I am not known for my skill in mathematics. Although my father was a maths teacher, it seems I didn’t inherit the gene. I struggled as far as O Level Maths (with remedial input from Dad) and then abandoned it with relief. Later, however, when I came into contact with the idea of sacred geometry, I did make my reluctant brain face up to certain mathematical challenges. The effort made me realise that grappling with number can help to stimulate deep layers of thinking, and has come in useful both for my own understanding, and for some of the books that I’ve written.

But the story here is more light-hearted – my own experience of encountering the powers of zero. Although zero itself is not such a light-hearted topic, I discovered, when looking into its history: ‘Within zero there is the power to shatter the framework of logic.’ More on that shortly, but I’ll start the memoir first.

There are no zeros in the world of the gods. That’s what I’ve been told, anyway. Vida, a friend of mine with a strong interest in the supernatural, pointed out that the number nought doesn’t register on the psychic plane.

‘It just doesn’t work,’ she said. ‘I proved it, with the Premium Bonds. I asked for £50,000, and visualised the number as powerfully as I could. I know that I shouldn’t really ask for money. But my daughter needed things for the baby. Thought I’d give it a go.’

‘And? What happened? Like the rest of us, you didn’t win, I suppose?’

‘Oh, I did. In the very next draw. But I only got £50. The powers-that-be didn’t recognise the noughts, you see.’

‘There’s a zero in fifty,’ I pointed out.

‘Well, they don’t do £5 wins any more,’ she said tartly.

However, as I discovered, it works both ways. The way in which the gods may disregard zeros can sometimes work in our favour. This is the tale of how I lost £200 through no fault of my own, but gained justice through the casual handling of these cosmic zeros. Or maybe it was deliberate? I’ve done my research, and have learnt that the gods sometimes take zeros into their own hands, not so much to retain their jealous power over them, but out of love, to soften the blows of fate, or to allow a little bit of cosmic luck to come our way. Although whatever the outcome, there’s usually a lesson in that too, for us mortals concerned.

Zero may be a relatively modern toy of the gods. The number zero is an invention, not an obvious concept from day one of human civilisation. ‘The origin of the symbol zero has long been one of the world’s greatest mathematical mysteries’, as the Bodleian library states boldly.

Although it is primarily a mathematical tool, it most definitely has a magical side too, and many cultures have considered it as having ‘darkly magical connotations’, as one reputable article proclaimed. Zero’s history is one ‘of the paradoxes posed by an innocent-looking number, rattling even this century’s brightest minds and threatening to unravel the whole framework of scientific thought…The clashes over zero were the battles that shook the foundations of philosophy, of science, of mathematics, and of religion.’ (Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, Charles Seife).

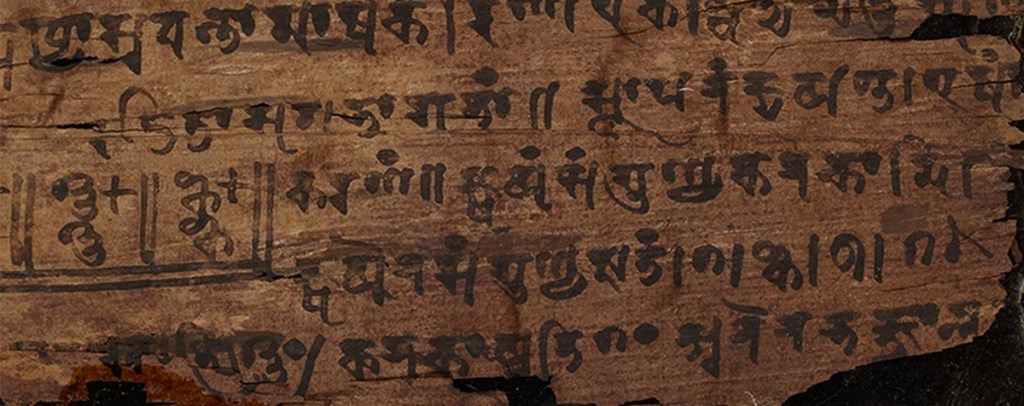

Zero arose independently in different parts of the world, but the version we have today probably began in Babylonia around 300BC, as part of the system for notating numbers. It was developed further in India from the 3rd or 4th century AD, as recent carbon dating of a manuscript proves.

It then spread both East and West – the Silk Road must have played a part in its transmission – and finally arrived in Europe in about 1200 AD, championed by the Italian mathematician Fibonacci.

As for the symbol we use today, it began as a dot, and then a hollow centre was added, turning it into the 0 symbol that we have today. Perhaps someone thought that a dot is a ‘something’ and that we really need some empty space in it to fulfil the underlying concept. (Could the creation of doughnuts, bagels and Polo mints have followed a similar philosophical evolution, I wonder?)

You can watch a delightful video by the Royal Institution about the origins of Zero: What is Zero? Getting Something from Nothing.

But back to the story – I’ll tell you what happened to me one summer, and you can decide for yourself whether zeros have a cosmic significance.

It was an August Bank holiday weekend, in the city of Bath. I’d been at a lunch party in the country on the Sunday, and drove home to a deserted street. I lived on a short Victorian terrace running up a hill. As you can see in the photo at the start of this post, the houses are set up high, and the road running below is bounded by a high retaining wall. It was conveniently close to the city centre, and thus usually choc-a-bloc with commuter cars on weekdays, and with residents, shoppers and visitors at weekends. But today it looked as if almost everyone had gone on holiday, so I had the luxury of gliding, rather than squeezing, into a parking space.

On that Bank Holiday Monday, my friend Erica came over from Bristol for the day, and when she left, I walked with her to her car. I could see immediately that something was up. Her car was parked safely at the top of the hill, but my red Golf was now skewed sideways along the wall, with a grimy white Toyota sitting too close to its bonnet. It didn’t take long to figure out that the Toyota had reversed with considerable force into the Golf, shunting it back into the wall, then rebounding a few inches forwards. The tow bar on the rear of Toyota showed traces of paint, and it had clearly left a corresponding dent on the front end of the Golf. I was flabbergasted.

‘Why on earth did someone do this? There was plenty of room to park.’

‘Looks as if he was drunk,’ said Erica. ‘You’ll have to report it. Would you like me to be a witness?’

I was grateful. Over the next few days I contacted the insurance company, and waited to hear from the owner. I even put a letter on the windscreen of the offending vehicle, inviting the driver to contact me. At once. Forthwith. Politely, so far – after all, it could have been stolen and returned after a joy ride.

One morning later that week, I drew open my bedroom curtains to see someone taking my letter off the windscreen. I recognised him as the man who lived further down the terracey: fiftyish, with a beaky nose and a loose-fitting fawn mac. A widower, someone had said. Ah, well if it was a neighbour, he would be round, once he’d had a chance to read the note.

I waited for another day, but nothing happened. Was he the type to get drunk, then crash his car? I’d heard he was fond of the cricket club bar, but he didn’t look quite that irresponsible. But you never know, do you?

By the end of the week, I’d put a note through his door, and contacted the police. Why didn’t I go round to see him? Why indeed – I ask myself that now, and the only answer – or excuse – I’ve come up with is that I had recently begun to live on my own, and that divorce can make you timid, and want to avoid further confrontations for a while.

‘How could he have done that and walked away?’ I fumed, as time slipped by, with no word from him. ‘He couldn’t have done it without noticing.’

The policeman who called at my house was sympathetic, but he’d seen evidence in the form of train tickets, proving that the widower had been in Cornwall at the time. The said widower also denied both lending his car to anyone, or having it stolen. Nothing to do with him, or his car, he maintained. This was plainly nonsense, but the same pleasant police officer said that without initiating a private forensic test to prove that the paint on the front of my car came from the back of his, there was no firm proof.

By now, my ex had heard of the mishap and offered to pay a visit to the perpetrator along with a friend. They planned to wear black balaclavas and brandish baseball bats. Just to frighten him, he said. Just to get an admission of guilt. It wasn’t his normal style at all, and I can only assume he and the friend had had a fun time the evening before, fuelled with a bottle of wine, planning this heroic rescue mission.

‘What if it gives him a heart attack?’ I said, declining the offer.

For a long and tedious time, it seemed as though my insurance company would triumph over his. Then they said as Erica was a friend, her witness statement was not evidence. Huh? Since therefore I couldn’t prove the other party’s guilt, they would charge me the £200 excess. I was left with a hole in my bank balance, and also in my understanding of this event. My best guess was that he’d offered a mate the use of his car while he was away – there was no disproving his story of visiting the son in Cornwall – and that the mate had gone on a binge, rammed the car, and left it without a backwards glance. The owner had probably thus invalidated his insurance, and in order to escape trouble was prepared to alienate a close neighbour. It was a bitter result, but I had to swallow it, unless I was to launch an independent court case. But there was more to come.

The allotments in Bath, surely one of the most beautifully-situated plots in the country. Mine is just visible at the forefront of the picture, with the apple tree on the right

Sometimes cosmic justice takes a while to pan out. The following summer, I bumped into the widower on the allotments which ran behind my garden. By the time I spotted him, we were so close that acknowledging each other was inevitable.

‘I’ve lost my cat,’ he said. ‘She might have gone away to die.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ I said. ‘I’ll look out for her.’

Why were we being polite, as if nothing had happened? Why was I being such a coward? The moment had come to change that.

‘I was very upset,’ I said, ‘when you didn’t respond to my letter. I think you’re aware that your car hit mine, but you wouldn’t own up to it.’

He looked sheepish. ‘I was going through a lot at the time. My wife had died.’

‘And I had just been divorced. I didn’t need the stress either. I lost my no claims bonus, £200.’

He played another hard luck card. ‘Well, maybe it was stolen. When I came to get the MOT, they found that the chassis was completely bent. Had to scrap the car. It was worth £2000 and I had to write it off.’

Hah! I knew then for sure that there was no thief. ‘If there had been, he’d have told the police. He lent or illegally hired out the car, and couldn’t claim on the insurance,’ I triumphed, inwardly.

And so the gods had been kind with their cosmic zeros, at least in terms of the overall balance sheet. The widower had paid three noughts for his misdemeanour. I had lost only two, and perhaps learned a lesson about cowardice.

References

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, Charles Seife (Souvenir Press – new edition 2019) ‘The Babylonians invented it, the Greeks banned it, the Hindus worshipped it, and the Christian Church used it to fend off heretics. Today it’s a timebomb ticking in the heart of astrophysics. For zero, infinity’s twin, is not like other numbers. It is both nothing and everything.’

Related books by Cherry Gilchrist