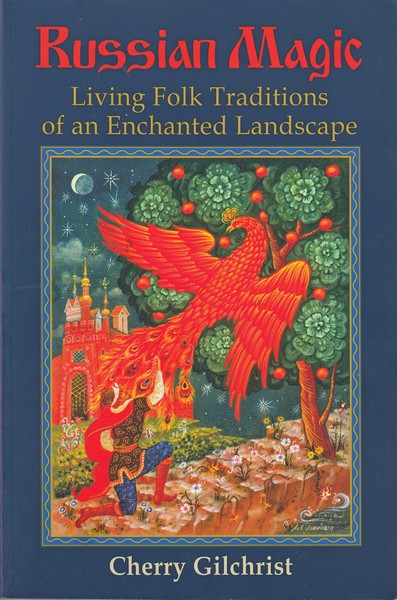

This post is adapted from ‘The Russian House and the Craft of Living’ – Chapter Three in my book Russian Magic (first published as The Soul of Russia). It’s the last of the current series of posts about my travels to Russia and the culture that I became immersed in.

The House as Microcosm

The traditional wooden Russian house (known as an izba) is a model of the universe, and a microcosm in its own right. Although the izba may look as though it only has a ground floor, closer investigation usually reveals a trapdoor in the ground floor leading to an underground cellar, and very often a ladder rising to an unheated attic room above. This symbolically embodies the three worlds of underworld, a human or middle world, and an upper world connecting it to the sky. The decoration use and lore of the Russian home is redolent with this symbolism, connecting it to Slavic myth, and the three vertical worlds represented in the ancient Russian Tree of Life.

‘The house, where many generations of a peasant family lived and died, was associated by its inhabitants with a small universe, connected innately with the world of nature and the Cosmos. Peace and harmony should be reigning in this well ordered world – once and forever.’ (Krasunov, p.12)

Everything in the traditional Russian house is charged with meaning. It is a vital living space laid out according to the rules of the cosmos, and in which certain rites should be carefully observed to keep it in good health as a home, and beneficial for the humans who live there.

The Human World of the Izba

As you enter the Russian home, you may have to stoop low as you pass through the doorway. This is deliberately done, so that anyone entering must show respect for the house, and in particular for the Red Corner, the sacred area of the home where the family icon is kept. Traditionally, the icon stands on a high wooden corner shelf, draped with an embroidered linen towel, and lit by a small votive lamp. In Orthodox culture, icons are not just religious images, but are considered to be holy objects, empowered in their own right as a gateway to the divine. The icon is also a charged symbol that represents the welfare of the family itself. In a TV interview, at the time of the Kursk submarine disaster in the year 2000, an old woman sobbed bitterly as she talked about her grandson, who was trapped at the bottom of the ocean: ‘The icon fell off the wall a few days ago,’ she sobbed. ‘That is a bad, bad sign.’

The Red Corner, krasni ugol, is thus called because the colour red means ‘beautiful’ in Russian culture. The word krasni for red comes from the same root as the word for beautiful, krassivi. This is a pre-Christian Slavic tradition, and the ceremonial linen towels are embroidered in red as the colour is considered sacred, and represents not only beauty, but the force of life itself. Russia is known as the ‘country of two faiths’, and it is plain that there are few boundaries between the Christian and the indigenous Slavic symbolism in Russia. The same towel that may be embroidered with figures of the Mother Goddess, the tree of life, and sky spirits in the form of horses, is used to drape the family icon in the mark of deepest respect.

The Stove

The polarity of Christian and native religion also reveals itself in the layout of the room. Diagonally across from the Red Corner, is the place where the stove often stands, the pechka that is also known as ‘the Little Mother’. While the Orthodox icon guarantees a link with the heavenly rites of Byzantium, the stove is the elemental crucible of life itself. A Russian proverb, which literally translates as, ‘To dance from the stove’, means ‘To begin at the beginning’: the stove is the origin and the perpetuator of life. Without pechka, there is no life in the home; she is the source of warmth and comfort that may actually keep the family alive during the long Russian winters. The pechka is multi-purpose – not only is it used for heating the home and for cooking, but traditionally it was also the place for sleeping. The classic construction of the stove is as a large box shape, constructed out of brick with a plaster finish; its flat top, six feet or so below the ceiling, provides an excellent sleeping platform.

The stove requires skill and patience to manage. In the village house that I owned in the same village of Kholui, I knew that I had to listen carefully when I was given instructions on how to light it, or my stays there in winter would be icy. The critical stage of the operation was to wait observantly for the time when the logs had burnt down, and the tiny, residual blue flames had been replaced by an orange glow. Only then was it safe to close the dampers, which would keep the heat in for another eight hours or so, the brick casing acting as a giant storage heater. Otherwise, deadly carbon monoxide can seep into the home, causing acute headaches or worse. I never did master the skills of drying mushrooms or making porridge overnight in the cooler ovens of the stove, but I learnt to respect the life and death powers of the ‘Little Mother’, and to love her gentle, penetrating warmth.

Food and hospitality

The other key feature of the traditional living room is the dining table, and to sit there is to be ‘in the palm of God’, as the old saying expressively puts it. By tradition, it would be set under the Red Corner, and much of family life would be lived around this table. Food and hospitality is a crucial part of Russian culture, both rural and urban.

The samovar, or ‘self-boiler’ as the word translates, is also a key part of Russian hospitality. It is sometimes seen as another symbol of the mother, along with the pechka and the Matrioshka doll. Its comforting curves, its decorative and gleaming brass, nickel or silver finish, and its near-boundless supply of hot water, make it a natural centrepiece for the tea table. Traditional samovars, as opposed to modern electrical ones, are heated by means of lighting a bundle sticks or some charcoal in the central funnel, which then in turn heats up the water in the large outer chamber. The tea itself is made separately, in extra-strong quantities in a small teapot, which is then topped up with hot water from the samovar itself. Samovars are still popular, and large versions are often used in hotels and offices as well as at home. But as a friend told me:

‘The best kind of samovar is the kind that you light with charcoal and twigs, and add herbs to as well. You can sit outside in the garden, breathing in the fragrant steam and having a cup of tea every now and then; it is happiness that lasts for hours.’

The best known ritual of hospitality in Russia is the welcoming ceremony known as ‘Bread and Salt’, khlebsol. A round loaf is used, in which a little hollow has been scooped out to hold a mound of salt; the loaf is placed on one of the long, embroidered linen towels, and offered to guests on arrival. Although the custom of Bread and Salt doesn’t take place on a regular basis these days, it is still often carried out at weddings, when the new bride enters the home of her mother-in-law.

The Underworld

After the bustling life on the ground floor of the house, the middle world, the descent into the cellar may seem dark and eerie. The cellar, or podpol, is a small room under the floor of the home, generally used as a place of storage, where root vegetables can be kept in a cool but even temperature through the winter, or jars of marinated salad and home-made apple juice left until they are needed. But in terms of traditional belief, it is known as the place of the ancestors, and the residence of the domavoi, or house spirit.

Domavoi’s name comes from dom, the Russian word for house, and he is one of the tribe of Russian ‘nature spirits’. These characters are temperamental, elusive, and tricky to deal with. They are akin in many ways to the mischievous ‘elementals’ of the Western magical tradition, or to the pixies and sprites of Western folklore. A domavoi is actually associated with a family rather than a house, and any family that moves house may have a difficult time ahead if they do not persuade their domavoi to come with them. One tried and tested method is to coax him into a sack, carry the sack to the new abode and then quickly offer domavoi a plate of porridge to help him settle down. Another is to cut a thick slice of bread and place it under the stove in the new dwelling. It is important to invite domavoi to come with you; even if he is capricious, the family needs him to be there.

Although domavoi is commonly associated with the ancestors, and the cellar of the home, he also likes to sit in the stove, and sometimes in the attic. In general, it is considered unlucky to see domavoi, for this can presage a death in the household. If you do see him, he should not be addressed as domavoi, but more often as ‘master’ or ‘grandfather’.( In various traditions it is common to avoid calling a magical creature by its real name; in Russia the bear is often referred to as Mishka, an affectionate nickname, rather than by its proper name of Medved, or ‘honey knower’.) You need to know how to recognise domavoi too, as like most nature spirits, he can appear in various forms. He might appear in the shape of a tiny, wizened old man, covered in downy hair, or as a tall figure ‘black as coal’, or even as an animal or a bundle of hay.

Is the belief in domavoi obsolete? Some Russians may well regard it as a quaint old folk belief, but to others the presence of spirits in the home and landscape is very real. On the island of Kiji, in the far north of Russia, I asked a woman from the regional city of Petrozavodsk what she thought about the domavoi. She answered me with great seriousness:

‘Every summer I come to work with tourists here, and I live alone in one of the old wooden houses. Oh yes, domavoi certainly exists. When I sit in this dark house at night, I sometimes hear a knocking, or I hear someone singing a melody. And even when I know the house is empty, I sense that there is someone upstairs. This is undoubtedly the domavoi.’

And a small post-script: I had just sat down to breakfast with my husband after writing this, when we were both startled to hear a loud knock come from the cupboard under the stairs. Thinking that one of the cats had got trapped in there, I opened the door to investigate. There was nothing to be seen. Except, perhaps, domavoi?

The Attic and The Upper World

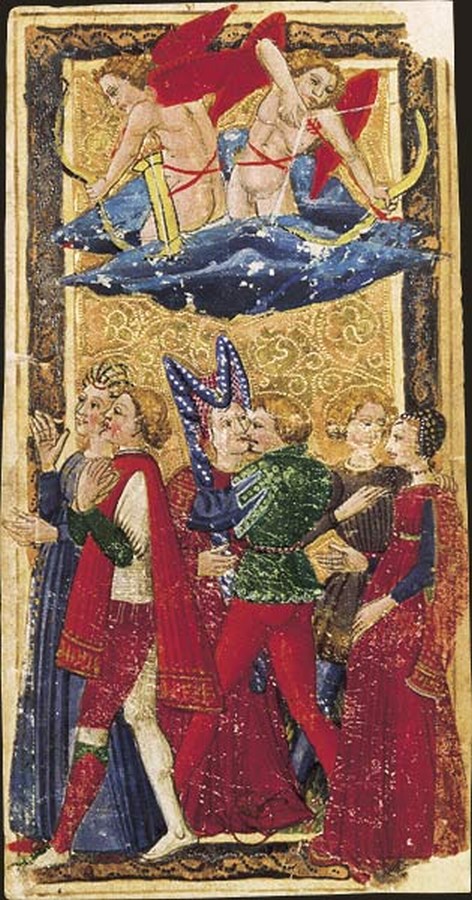

Many Russian houses have an unheated attic room, used mostly in summer. It is often known as svetelka, a word associated with sunlight, and with the sun itself, which is considered to be the protector of the home. Its lofty position was said to be beneficial for young girls, and would help to guard their innocence. However, although unmarried sisters and their girlfriends might officially sit up here together to sew or spin, it was also the place for divination, especially in matters of love. Here they might unbraid their hair, an action which would loosen the bonds of the everyday world, and invite the powers of magic in. While their mothers believed them to be safely occupied with spinning and needlework, they would gaze into a mirror to see the faces of their future husbands, or tell fortunes by interpreting the shapes of melted wax dropped into a bowl of water.

Within living memory, the women’s tasks of spinning and weaving were key activities in country life, and discarded spindles, distaffs and spinning wheels can still readily be bought at flea markets. It was not only a practical occupation, but also symbolised the bringing of order and civilisation to the community.

Mokosh the old Slavic mother goddess played a particular role in relation to spinning, and another female household spirit called Kikimora presided over distaff and loom. Kikimora was quick to punish any women who did not put their spinning and needlework away tidily at the end of the day! She might, however, help out the diligent housewife by taking on some of her work at night.

Distaffs were often highly decorated, painted in lively colours with human figures, animals, and geometric motifs.

The attic, therefore, could be a place both of light and innocence, and of magic. The sky world is related to the top part of the house, which is often decorated externally to reflect this. In the Volga region especially, the protruding end of the ridgepole is frequently fashioned into a form of a horse, known in Russian mythology as a sky creature. Symbols of the sun, such as cockerels or circles with rays around them, and those which signify heaven, like peacocks and bunches of grapes, are commonly found carved into the upper part of the house façade, and boards covering the ends of the roof beams are commonly known as ‘wings’.

The Bathhouse

The bathhouse has been an important part of Russian life since time immemorial, and the custom of weekly steam bathing in an extreme temperature was noted with surprise by early travellers to Russia, one of whom described it as ‘a veritable torment.’ Saturday night is the traditional Russian day for bathing, said to be a choice of day originated by the Vikings.

The bathhouse is a house in miniature, built out of wood with a pitched roof and its own small chimney. It usually stands apart from the izba to avoid the risk of fire. Water is heated in a copper in the lighted stove, and the art of bathing involves the skilful creation of steam to the required degree. There are various stages in the ritual, such as rinsing oneself with warm water and then lying on one of the wooden benches before engaging in the more intense process of steaming. Switches of birch twigs (venniki) are used for one person to flick or whip another with; the sensation is light and stimulating, and far from painful! There is a tradition that the birch should be cut in early summer, when at its most potent. The family whose bathhouse I used told me that they try to gather them around June 24th, the old Russian midsummer festival.

The bathhouse is inextricably bound up with magic and divination. Any spell or charm is most potent when cast at midnight in the bathhouse. The role of the bathhouse is considered by some authorities to be that of a pagan temple relegated to this warm and steamy place after the old religion was displaced by the coming of Christianity. The rituals once carried out on the bride’s wedding eve were always conducted in the bathhouse. This was an occasion for women only, usually with just the bride’s girlfriends present, though sometimes with the male village sorcerer in attendance too. Girls hoping to marry would take away some of the bathing water to ensure their future luck.

Playful versions of divination in the bathhouse for love still take place today. Girls set up a deliciously scary ritual, in which they go into the bathhouse one by one, into an atmosphere thick with steam, and feel around until they touch someone’s hand. The type of touch they encounter tells them what kind of husband they will marry– if it’s a hairy hand, he will be rich, if smooth then he will be poor, and if wet, he will certainly be a drunkard! In practice the game is often aided and abetted by the local boys, who enjoy taking a turn to hide in the bathhouse and frightening each of the girls in turn.

The Bannik

The spirit of the bathhouse is known as the bannik. Like most Russian domestic spirits and nature spirits, he is a shape-shifter, who can change his appearance at will. For much of the time, he is not seen at all, since he owns a cap of invisibility, but he might appear in the form of a large black cat, or perhaps as an old man with a green beard. Bannik can also manifest as a heavy stone or a burning coal, so potentially he could be around in the bathhouse at any time, making it a place of menace, as he is bad-tempered, and brooks no breach of etiquette. Students working on Kiji Island (in the far north of Russia) during their summer break told me that they always treated bannik with great respect. One of their number, an intellectual young man who thought he knew better, refused to ask bannik’s permission to enter the bathhouse as required, and neglected to leave a little offering of soap or a fir twig for the bath spirit as is the accepted custom. The next time he entered the bathhouse, he tripped over, dropped his glasses, and trod on them by mistake. Stooping down to retrieve the now broken glasses, he stood up too abruptly and cracked his head on a low beam. Since then, his friends reported, he has always shown the proper respect to the spirit of the bathhouse.

Potent, risky, pagan, but also a great source of pleasure to almost every Russian today, the bathhouse retains its position in the heritage of Russian traditional culture and magic.

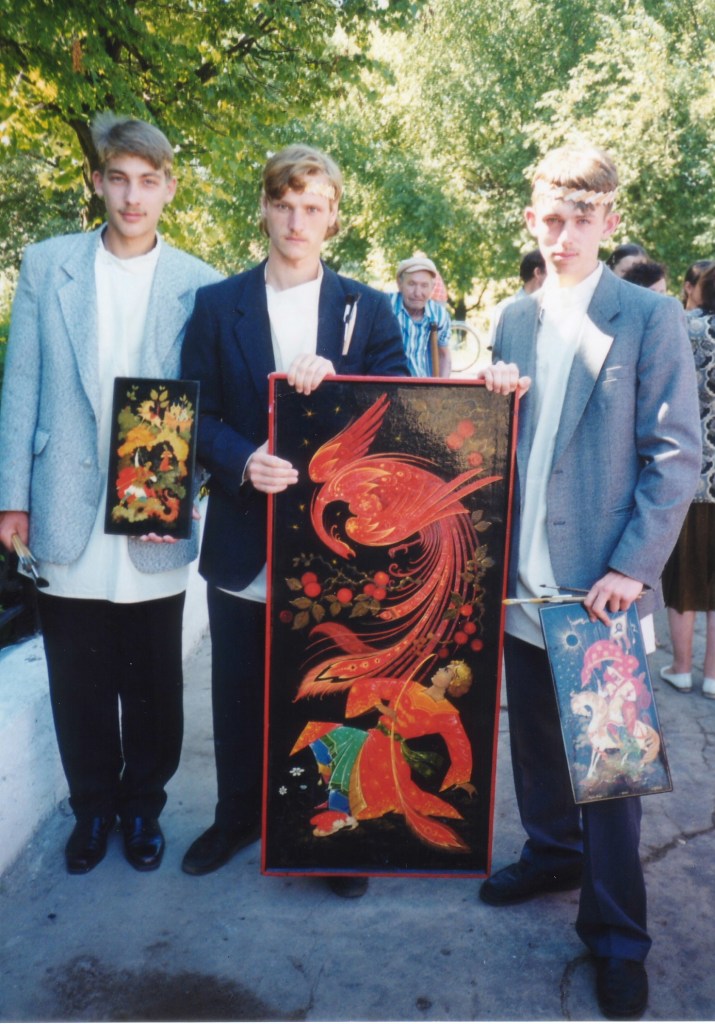

Decoration of the House

There is an intense love of colour and decoration in Russia, and the country is rich in arts and crafts. Houses are often decorated on the outside with wooden carvings, and home owners compete with each other to create the finest of these. As well as symbols representing the sun or sky in the upper parts, there may be carvings of lions or mermaids to protect the home, birds to symbolise happiness, and beautiful descending panels of fretwork on the front wall, imitating the embroideries on the ceremonial linen towels.

The most prominent and typical decorative feature of the izba is the carving around the window: lacy fretwork window frames known as nalichniki, which incorporate a variety of motifs, often rosettes or floral designs, and sometimes even the Communist five-pointed star. As for the origin of this custom, one suggestion is that it is a way of protecting the home, by guarding the windows against the entry of evil spirits. The other is that it provided a beautiful framework for an unmarried daughter as she sat sewing at the window, ready to catch the eye of any eligible young man strolling by.

Text and photographs © Cherry Gilchrist 2020

Related Reading

Gerhart, Genevra (1994) The Russian’s World, Holt, (Rhinehart & Winston, USA)

Fraser, Eugenie (1984) The House by the Dvina: A Russian Childhood (Corgi, UK)

Hubbs, Joanna (1988) Mother Russia, (Indiana University Press)

Milner-Gulland, R. (1997) The Russians, (Blackwell, USA)

Billington, James H. (1970) The Icon and the Axe, (Vintage Books: Random House, New York)

Gaynor, Elizabeth & et al. Russian Houses, (Benedikt Taschen Verlag – no date).

Hilton, Alison (1995) Russian Folk Art (Indiana University Press)

Ivanits, Linda J. (1992) Russian Folk Belief, (M.E. Sharpe Inc.)

Krasunov, V. K. (ed.) (1996) Russian Traditions, (Kitizdat,Nizhni Novgorod)

Rozhnova, P. (1992) A Russian Folk Calendar, (Novosti, Moscow)

Ryan, W. F. (1999) The Bathhouse at Midnight (Sutton Publishing Ltd., Stroud)

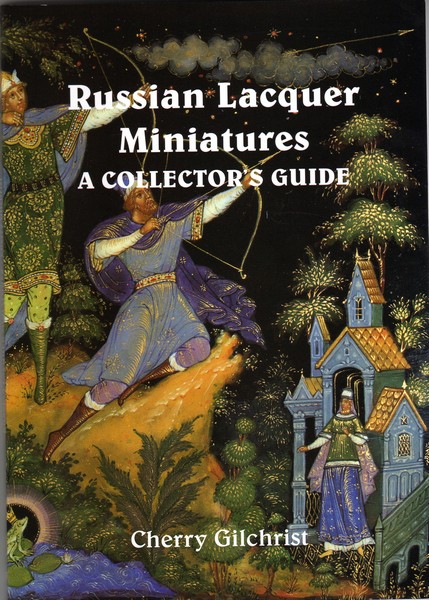

Russian Magic – You will find much more detail about the Russian izba and traditional way of life, with folk customs, fairy tales and Slavic mythology, in my book Russian Magic, which is available in printed and electronic form .