Crazy Times in Cambridge – Part Three

I’ve posted two blogs already about ‘Crazy Times in Cambridge’, but this third will deal with some seriously mad enactments, rather than just student exuberance and defiance.

In the early spring of 1969, a bunch of assorted students, friends and townies began to rehearse for a production of Marat Sade in Cambridge . Or, to give it its full title, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, written by Peter Weiss. It’s a play within a play, set in 1808, and featuring the inmates of a French lunatic asylum fifteen years after the French Revolution.

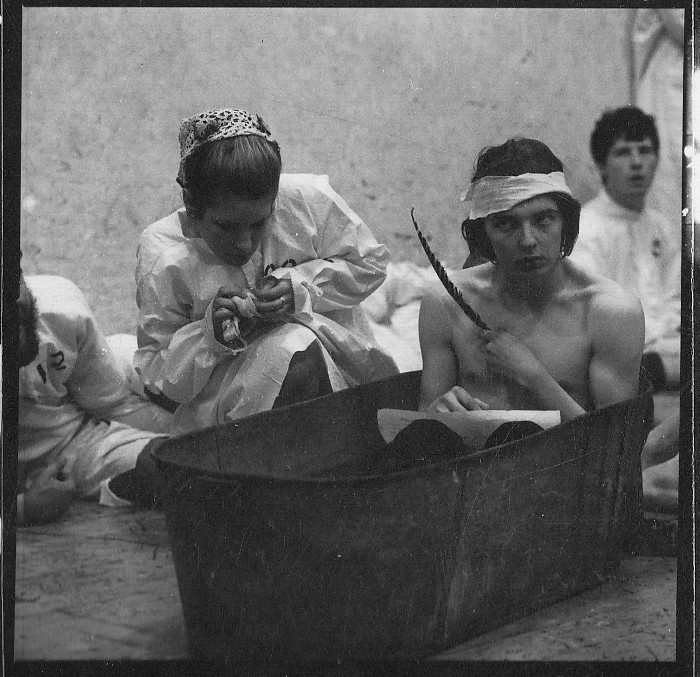

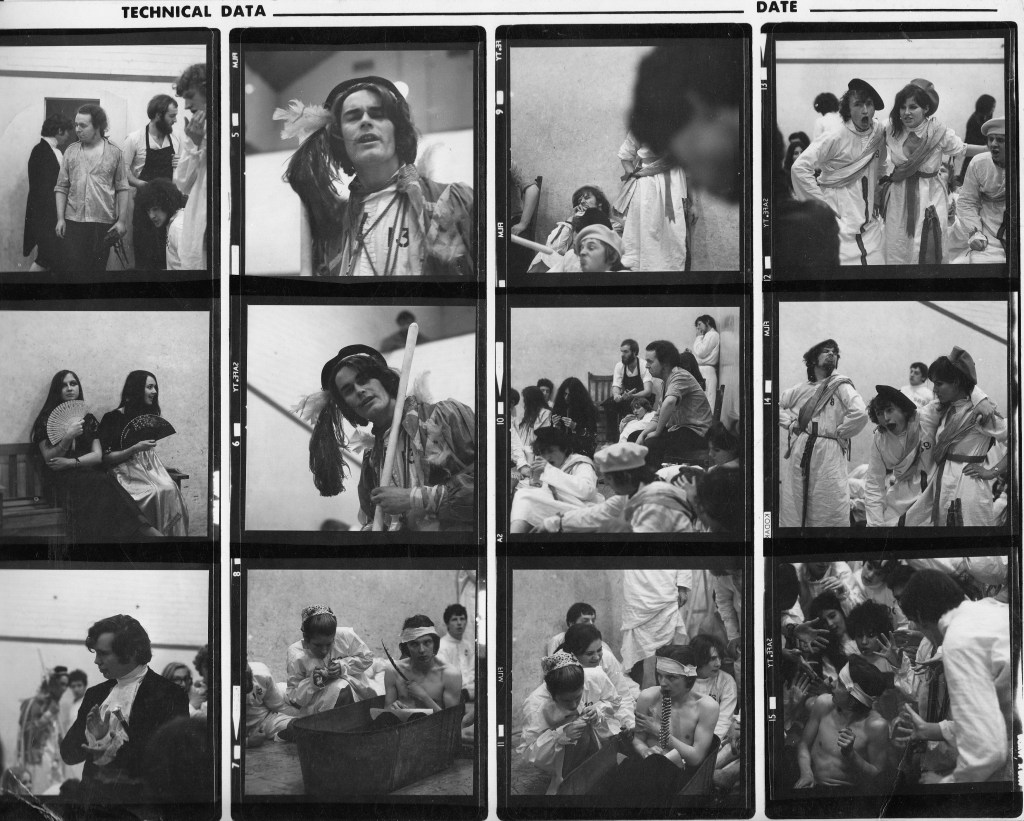

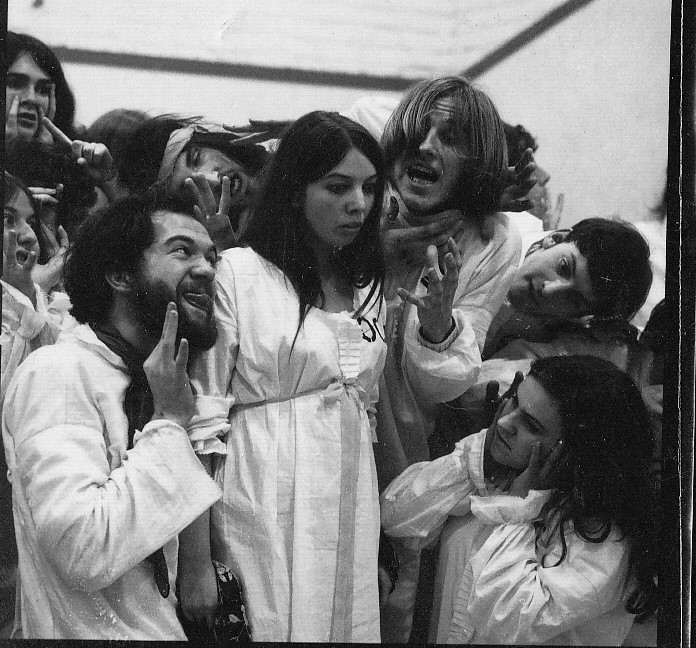

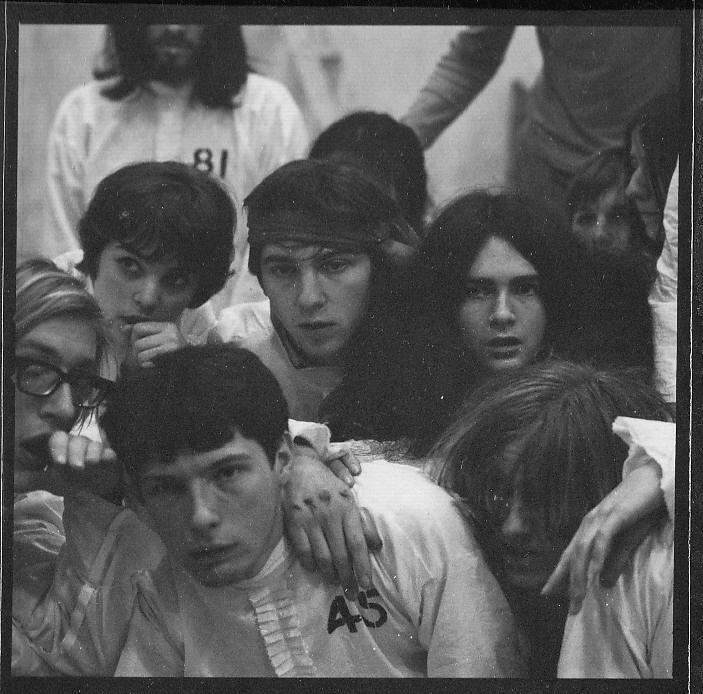

I’m proud to say that I was one of the insane band. We gave our all to the madness and chaos. Bruce Birchall, our alternative-style theatre director extraordinaire, strode around in rehearsals, thwacking his tall boots with a whip, in a suitably de Sade manner. It was a stirring, primeval experience, which took up a disproportionate amount of both our study and leisure time, but engaged us completely. When we performed at Peterhouse College, one friend in the audience reported, ‘At first I was just looking at students acting as lunatics. But then you really did become lunatics.’ Praise indeed.

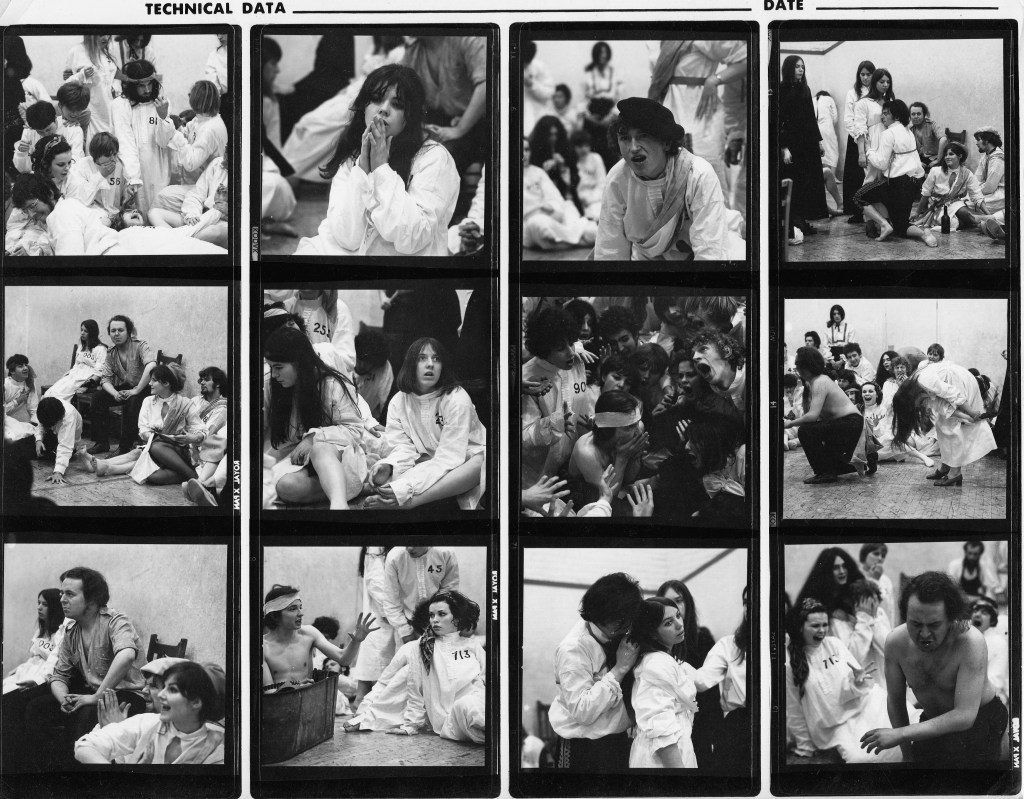

The photos below are taken from the sheets of contact photos for the production, which I’ve managed to keep hold of all these years.

One of the poignant aspects of looking at these photos now is to ruminate on what became of those who took part. I have followed some over the years, and caught up with others more recently, thanks to the ease of Internet searching. Here are some of our varied destinies: human rights lawyer, initiated as shaman in Siberia, financial journalist, expelled from Cambridge for drug dealing, local radio commentator, imprisoned as member of the Angry Brigade, advertising executive, writer, died young of natural causes, computer scientist. A mixed bag.

However, while doing the original research for this blog researching for this blog, in 2012, I was sad to discover that Bruce Birchall had died the previous year before in 2011. But a conversation about Bruce’s demise was to be found here.

As David Robertson remarks there (another of our troupe at the time): He was an ‘interesting’ indeed extraordinary character; some would say ‘colourful’; others, ‘impossible to manage’. He was both generous with his time, and relentless with his views. In the time I knew him, he would pick an argument in an empty room. Yet beneath a personal presentation that owed no debts to genteel bourgeois conformity, or even hygiene, lay a sharp mind, albeit one distorted, some would feel, by an intimidating monomania.

I’m afraid the ‘poor personal hygiene’ comment really was true! You didn’t get too close. As Margaret, then the flatmate of Gill, David’s future wife, also confirms: We used to hide the hairbrush when he came round as he had chronic headlice and would pick up the brush, stand in front of the mirror and brush his nitty knotty locks. He would look for it, and we would have to say ‘Oh where can the hairbrush have got to?’

Others have written up their accounts of Bruce during his post-Cambridge years, when he headed into urban radical theatre, squats, street events and the rest. He was also a grand master at chess, and some have remembered him almost solely for that. A brief resume remains here and another memoir can be explored here.

Bruce and the Heir Hunters

Bruce Birchall was also the subject of an edition of ‘Heir Hunters’, a popular television programme chasing up inheritors of unclaimed estates. (Series 7, episode 6, aired July 14 2014), announced with the description: ‘The heir on another estate tries to learn more about her deceased cousin, a chess champion and radical playwright.’

From this I learnt that his mother was from an Austrian or German family, with the name of Wasservogel (‘Waterbird’), and his father was Sydney Birchall. Bruce was an only child. The estate he left was £100,000 – no one knows how he amassed this money. He certainly never seemed to have many worldly possessions, and was living in a Housing Association flat in West London when he died.

The heirs traced were his two first cousins on his father’s side, one of whom, Hilary, spoke about her childhood recollections of Bruce on the programme. He later became the ‘black sheep of the family’, chastised for not knuckling down to a proper job. A friend of Bruce’s from boyhood, Bill Hartstone, had come to see Marat Sade and said it seemed to be full of ‘dangerous-looking lunatics’. (Excellent! Just what we intended.) He also reminisced that Bruce had once played in a chess championship wearing a bathing costume – probably for practical reasons of heat in the competition room! Everyone interviewed, including the playwright David Edgar, agreed that Bruce was very clever.

Only two photos of him were shown, from boyhood -and if I try searching on Google images, the only ones which come up are the ones that I’ve already posted from the Marat Sade production.

Updating scenes of madness

My first post about Marat Sade appeared in 2012, on my former blog at www.cherrygilchrist.co.uk (my blog has since migrated to here to Cherry’s Cache, in a different and I hope enhanced format). It produced a goodly flow of responses from others who remembered the production as a stand-out event in their student years; it even led to some happy reunions, as well as a lot more reminiscing. I’ll continue here with some of these conversations.

Did I remember, asked Isabel, the beautiful blonde standing above the crowd of lunatics, that we were dressed in real shrouds? No, I did not.

Did I also know that it was Julian Fellowes, of Downton Abbey fame, who played the asylum’s director? Hah! I was vaguely aware that we were at Cambridge at the same time, and hadn’t been able to remember which one he was. Hello Julian – now Baron Fellowes of West Stafford – you were already practising the aristocratic role that would come your way later!

Did I recall, asked Tim, that he had been crucified as Jesus in the production? Ah, yes…he had a splendid dark beard and long hair which made him a natural for the part.

And ‘she died young’, I was told by Margaret, pointing at the photo of the Dutch girl who had once described me as ‘very, very untidy’. As Else was some kind of anarchist, it seemed to me ridiculous then that she should notice or care about such things. Now I feel sad that she left us a long time ago.

We were all, also according to Margaret: ‘So young! so pretty! so mad!’

In another photo, that features my own non-starring role, I can also see the hand of Chris, my future husband (bottom right), placed on the shoulder of the guy next to him. Note the black marks on its knuckles. This was the result of us joining in the student protest in March 1968, against Denis Healey – you’ll find the account in my earlier blog **** of how a policeman stomped on it

To crown this rather haunting experience of revisiting Marat Sade, I’ll add here some extracts which Isabel sent me from letters written to her mother at the time. (Included here with her kind permission.)

On 9 February 1968, she wrote:

“Sunday morning dawned bright and clear and I ventured forth to audition for the part of a mad woman in Marat Sade. I went to a rehearsal on Wednesday and we had to do the most amazing things. Still it was huge fun and like the man said – “What’s the point of a revolution without general copulation?”

On 14 March her mood was darker, but triumphant:

“The production of the Marat Sade has been going like a bomb. However, it’s terribly scaring and I spent the whole of Tuesday night having the most vile nightmares. I’m very proud of the fact that a large blow-up of a mad-me is adorning the window of Bowes & Bowes – FAME at last.”

Crazy times indeed.

See also:

Crazy Times in Cambridge Part One

Turbulante Times in Cambridge (part two of ‘Crazy Times’)