This post is being published a couple of days earlier than the usual Sunday morning slot, to celebrate VE Day. I’m proud to be sharing Noel’s story with you to mark the occasion.

Many ordinary lives conceal extraordinary stories. I’ve had the opportunity to listen to some of these stories, sometimes when researching for a book, sometimes just out of a strong personal interest. This is the first of an occasional series of posts about such lives, Noel Leadbeater’s story of what she did in World War Two. In the current state of the coronavirus crisis, many of us may be thinking about how the challenges and restrictions compare with wartime, and wondering about the efforts that people made to try and keep their country safe. Some of these were never revealed until many years later.

Noel Leadbeater (née Davies) would never tell us what she did in the war. Her daughter Helen was one of my closest friends, since after my parents moved house as I was about to go into the Sixth Form, I lived with the Leadbeater family in term time. Noel was one of the liveliest, most amusing and kind-hearted people I have ever met. She was also a natural raconteur. However, ask her about wartime, and she clammed up. She might mention the Land Army and the ATS in passing. ‘My lips are sealed. I signed the Official Secrets Act,’ she’d say dramatically, when pressed for more detail.

Finally, the secrecy around the operations evaporated, and she was free to tell her story. She had become a member of a hidden army of Morse Code operators, trained to record German signals. The coded messages they took down were then sent to be deciphered at Bletchley Park. Which, as you may be aware, was the place that broke the highly-encrypted messages sent by the Germans via the Enigma Machine.

I visited Noel in 2010, just before her 90th birthday, so that I could record this story in full, and preserve it not just for her family but for a wider audience too. It’s presented here in a slightly shortened narrative version. On my visit, she was full of life and fun as usual, and as bright and sharp as ever. But it was the last time I was to see her, since she died just over a year later.

Noel at the start of World War Two

Noel, née Davies, was born and brought up in Birmingham, where she was one of a large working-class family. Although intelligent and keen to learn, any proper education was out of the question as she was expected to to help at home with her siblings, and to go out to work as soon as legally possible. Nevertheless, as the story will show, her abilities were clearly recognised in wartime, and in later life she educated herself in literature, worked as a teaching assistant, and completed an Open University degree.

Early on in the War, Noel joined the Land Army: ‘Not because I loved the land, or anything else, but I just loved the uniform!’ However, she became ill after the very strenuous work, and switched to factory work instead, working with a company called Avery’s who made weighing scales. ‘There was quite a lot of bombing in Birmingham, so I never knew when I went into work whether the office would be still standing, but it was all right.’ Luckily for Noel, she didn’t stay there too long, since a history of W. & T. Avery records: ‘During the second world war the company also produced various types of heavy guns. At that time the site underwent severe damage from parachute mines and incendiary bombs.’

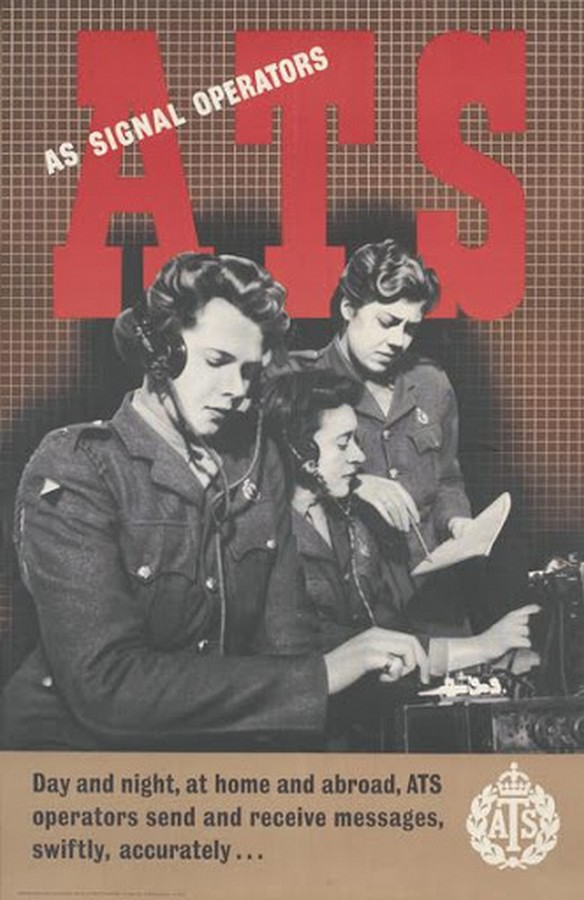

Call-Up, and the ATS

Then came the compulsory call-up for women, and Noel joined the ATS (Auxilliary Territorial Services) :

‘I had to report to a little town called Droitwich which is near Birmingham, in Worcestershire, and I went on the train with several other girls from Birmingham. We were met at the station by a corporal and a sergeant.’ There, they were put into threes, and told to march into the town. ‘But one unfortunate girl called Janice, her mother had insisted on coming with her! And this woman, she couldn’t march in the road because the sergeant wouldn’t let her, so she was hopping on and off the pavement, into the road and back again. And the poor girl was saying, “Our Mum, our Mum! Do go ‘ome again, our Mum!” But the mother said, “I promised your Dad I’m going to see you into those barracks, and that’s what I’m going to do.”’

At their destination, a hotel that had been commandeered, Janice’s mother was speedily sent home, and the girls were kitted out. ‘We had to go into what must have been the garage earlier on, and we were issued with our kit. Well, we lined up and marched into the garage, and there was a sergeant there – she didn’t bother with things like measuring tapes, she just looked us up and down and said, “Tall – thin – skinny – number three!” Or, “Short -fat – number one!” And we processed along a counter where we were issued clothing. Two skirts, two tunics, shirts and collars and blue stripe pyjamas, and then it came to the greatcoats. The girl behind the counter looked me up and down and said, “Haven’t got your size.” She spoke to the sergeant who said, “There’s some men’s greatcoats in there. Give her one of those!” So I was issued with a man’s six-foot greatcoat.’

In their allocated huts, the new recruits got ready to transform their status: “We all proceeded to put on our uniform, because we were very proud of it. But we were all different sizes, and some of the skirts came nearly down to the ground, and some were – oh, we did look a mess! And when I put my great coat on there were hoots of laughter, because it was nearly on the floor, and the sleeves covered my hands. But when I grumbled to the sergeant about it she said, “Oh you don’t have to wear it dear! As long as you’ve got it. When you get to your next posting, just go to the stores, and they’ll change it for you.” Which really was very typical of the army, I thought.’

The first day ended with the ‘Lights Out’ bugle call at 9pm. ‘Which to me was wonderful because I thought, “Well, now you know you’re in the army!”’ Their training was general to start with – learning about the ranks of the army and taking various tests. Then they were asked what section they would like to be in. Noel’s first choice was to be a driver, but as she couldn’t drive already, that was refused. ‘So then I said I would try “Ack-Ack”, which was anti-aircraft guns. We had to do various tests for that, lying on our backs and looking through binoculars – all sorts of things. And I thought, “Oh well, I shall enjoy this.” But then one day, one of the officers called me in to speak to her, and we had quite a long conversation. And she said, “I think I’ve got a job which would be better for you, and that you’d like, but you mustn’t tell anybody about it. It’s very hush hush, and you’ll have to go up to London for some more tests.”’

This was the start of her transition into the Signallers, and her Morse Code training. To begin with, she was posted to London, staying in a hostel in Gower Street which had previously been accommodation for shop workers – it was usual at the time for the bigger London stores like Heal’s or Gorringe’s to house their female workers ‘safely’ in hostels. ‘The main test was to see if we would be suitable to take down Morse. They didn’t send Morse as such, but they sent sounds.’ She recited a string of ‘da-dee-da’ syllables in varied pitch and rhythm. ‘You had to put a tick or a cross whether it was the same sound or not. Then we had to write an essay – there were all sorts of tests, and in the end, some people went back to their unit. But some of us were then held in Gower Street until there was a place for us at the training centre, which was at Trowbridge in Wiltshire. There were thirty girls, and we were going to be known as 37 Squad.’

ATS in the Film Studio

One day, as they lined up to be assigned their daily chores, like washing the windows or cleaning the dining room, the officer in charge said, ‘I want six girls who can play table tennis.’ Noel hesitated: ‘I couldn’t play table tennis, and my father, who had been in the First World War, had said to me, “Never volunteer for anything! Keep your head down.” But I thought, “Oo- table tennis – that’ll be nice!”’

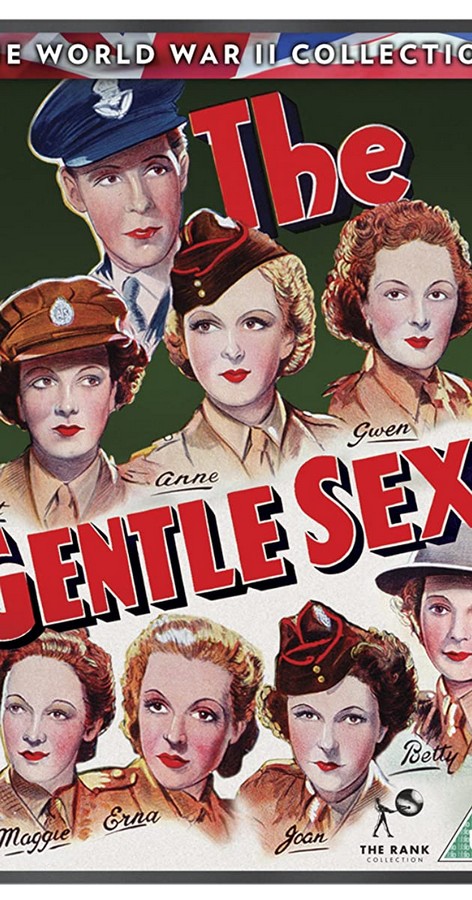

She stepped forward, and she and five others were then given travel warrants. Much to their astonishment, they were sent off to a film studio. ‘And for that day, we were ATS in a film called The Gentle Sex.’ The film was made as propaganda, showing a somewhat romanticised but detailed version of life in the ATS. The set for Noel’s scene was designed to look like an ATS recreation room in an ATS centre. ‘Then a chap called Lesley Howard, who was a film star and also a director, came in and said, “Now, you are supposed to be playing table tennis in this scene, so come along to the table.” I’m afraid that not one of us could actually play table tennis! And he was really, really cross. So in the end, they got one of the cameramen to play at one end, and one of the stars at the other. But of course you only saw his hand, and the bat – you never saw him. And we were all in disgrace. So we stood there, and he suddenly pointed at me, and said, “You!” I almost fainted and just managed to say “Ye-es?” Then he said, “You’re too tall! Stoop down or something.” I did what he told me, and made like Quasimodo, and crouched there. And this went on practically all morning – this poor cameraman, sending the ball, and the film star sending it back.’

She and her ATS comrades were told to stand around, admire the game and clap. But they were just a backdrop to the ATS actresses. ‘They didn’t wear the same uniforms as we did. Their uniforms were all carefully tailored, in a different material, and they looked super in them! And there was us in our rough tweed and serge, looking terrible.’

But it wasn’t all bad news. They dined in the canteen with the stars: ‘We sat where we could observe them. Oh, and they all smelt lovely! Their lovely perfume…and our Lifebuoy and Wright’s Coal Tar soap faded into the background.’ And after a further brief stint of filming after lunch, they were actually paid – a welcome surprise: ‘I think we were given something like seven shillings, or eight shillings. I’ve seen the film, of course, many times, and honestly – that day’s work is condensed into about three minutes. You just see my head bobbing up and down! But we did enjoy it, and of course when we got back the other girls were furious.’ The next day, when the officers asked for seven recruits, plenty of the girls who’d missed out stepped forward eagerly, but they were only signed up for domestic tasks rather than the glamour of a film studio!

Images for The Gentle Sex, a propaganda film, showing a factual though somewhat romanticised version of life in the ATS.

The next stage

‘Well, then, as I said, thirty of us formed this 37 Squad and went down to Trowbridge in Wiltshire.’ This is where the Morse training began, going at a very slow pace. It was a long process to accustom fresh ears to distinguish the different Morse signals, some nine months in all. ‘Longer than an air crew, because it had got to be perfect. We were told we could not make mistakes’ If they weren’t sure of a letter, then they had to leave a blank and not put it down. Otherwise: ‘It could cause such a lot of trouble. This was dinned into us, and of course the need for secrecy. We had to sign the Official Secrets Act.’

‘We did our training in Nissen huts in a sea of mud.’ That was a disaster for Noel’s new shoes. ‘They couldn’t fit me with two pairs of shoes, so I had one ordinary pair and one officer’s pair. Oh, the lovely pair! I used to polish them every day. But of course with this mud, they didn’t look so good.’ (On reading this transcript, Noel’s daughter Helen said: ‘She was still talking about those officers’ shoes, years later. I don’t think she ever had a pair of shoes she liked as much.’)

The huts and the sea of mud caused other problems too. Once, Noel was sent off to see a major in his hut for a review, and when she left, she couldn’t work out which direction she’d come from! ‘I stood in the mud and thought: “Which hut did I come out of?” I hadn’t got a clue, because they all looked the same! So I went across to the nearest hut and opened the door, and they were all men, signallers, and they wolf whistled and shouted, and their sergeant said, “Shut up!” I backed out quickly, and went to another hut. These were girls, but not any girls that I knew. So after visiting about four huts, I said to the sergeant in charge, “I’m in 37 Squad, and I don’t know where it is!” She said, “Try that one.” Much to Noel’s horror, when she entered the door pointed out, she found herself back in the major’s hut again. ‘I could have died! And he said, “You’ve just been in here! And your shoes are dirty.” And I, forgetting where I was, said, “Yours would be dirty if you’d just walked through all this mud!” So that wasn’t very successful. I’ve never made up into corporal or anything, and I think it was that interview that did it.’

Marriage and the Isle of Man

The training began in the autumn 1942, and the following January Noel was given an extra week off, known as Marriage Leave, for her wedding with Raymond Leadbeater. In her absence, the rest of the squad was told that they were leaving Trowbridge, to finish their training in Douglas on the Isle of Man. ‘It was very hush hush.’ Noel had to follow later, after her honeymoon, catching a boat alone and suffering terrible sea sickness en route.

‘I kept thinking, “Oh please let a submarine come and shoot us down, and we can go to the bottom of the sea!” But the minute my feet were on the ground, I was OK.’ OK enough to go off with her friends who were waiting on the quayside, for a free meal of egg and chips.

Squad 37 was billeted in boarding houses, where apparently Italian internees had been living. ‘I didn’t understand what they’d written on the walls, but the powers-that-be sent soldiers with whitewash to cover it up!’ Every day, the squad members marched up the hill to ‘quite a nice hotel’ for their Morse sessions. The two male drill instructors, one short and squat, the other tall and thin, sent the girls into fits of uncontrollable giggles when they gave out orders for the drill. ‘They used to get so mad, and scream at us, “Stop that!”’ Although the girls liked their instructors, they couldn’t curb those giggles. ‘We just couldn’t – we just couldn’t.’

But it was becoming a serious business. ‘We now became aware that we were going to listen in on German messages.’ They were trained to get used to background noise, and to pick out the individual ‘voice’ of their operator. ‘And this was quite difficult. But in the end, we all passed, and we then really became Signallers.’

The return crossing to England was smooth, and Noel travelled back to her home town of Birmingham by train on April 30th, 1943. She remembers what a delight it was to see the countryside again. ‘There are not many trees in Douglas – it was so lovely to see all the trees, so green and fresh. And I had a week’s leave at home – of course I was married by then.’

Final training

After this, the ‘girls’ were sent to Loughborough, in Leicestershire. ‘There we did the final training for the job we were going to do. It really was quite traumatic because we had all this noise and interference, and you had to learn – in the way that you recognise a friend’s writing on an envelope – we had to learn our Jo’s method of sending the Morse. They were all different – it was amazing!’

The skill was not just in notating the Morse, but in finding their individual ‘Jo’ (probably a term for a Jerry or a German) on the wavebands. The transmitters often changed frequency. ‘So we had to carefully track them down and be sure that it was ‘our’ chap.’ Noel thought it was likely that each ‘Jo’ they followed was also being followed by another trained operator in the UK, as a double-check.

Beaumanor – a ‘Y’ Intercept Listening Centre

In Leicestershire, the squad was stationed in the village of Woodhouse Eaves, once again in huts in a field. However, the actual work was carried out at Beaumanor house, a grand stately home, to which they were transported by troop carriers. As a recent article about the centre says:

Beaumanor was a highly strategic “Intercept Station”, concerned with monitoring the enemy’s main channels of wireless traffic and communications. The “Y” Intercept Listening Service operated from 1941 to 1945 and its wartime activities were as top secret as those at the Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. By the end of the war, there were more than 1,200 ATS women operators and 300 male civilians working at Beaumanor.

Much of the monitoring took place in specially built huts in the grounds of Beaumanor, many disguised as cricket pavilions and greenhouses to confuse spies and nosey neighbours. Civilians and girls of the Auxiliary Training Service were the main members of staff, each having their own allocated part of a radio waveband to monitor for Morse-coded messages. Leicester Mercury, 7 Feb 2020

Despite the seriousness of the work, the recruits learned to unwind and enjoy each other’s company.

‘Oh, it was quite fun really! We did have a lot of fun, in spite of the work. I mean, we all knew it was absolutely vital, but at the same time, we were only girls. And we did have our fun.’

The job itself was so strenuous, requiring such extended concentration, that they weren’t asked to do any extra chores. Once they were qualified to join these ‘ops’, they worked in four watches throughout the 24 hours. ‘So the Set Room, as they called it, where all the wireless sets were, was never ever empty.’ Transitions from one shift to another went as seamlessly as possible. The other girl would just get up and say, “He’s here,” and show us where on the dial.’ But even that didn’t hold, since the frequency could move, and the signal would have to be tracked down all over again. ‘We really, really did work so hard. But, as I say, we did have a lot of fun. Sometimes the girls would get a tin of condensed milk, and we’d make toffee over the stove in our hut. We got to know the girls we were with very well, of course, and I was friendly with so many of them. It was a lovely, lovely time – I mean, it wasn’t a lovely time! It was terrible with everything that was going on – but the companionship was so wonderful. I’ve never really found that since. And we all felt that we were really doing a very good job in the work that we did.’

(Source Leicester Mercury)

‘All our messages went to Bletchley, either by motorbike or on the tele-printer. The work we were doing was monitoring the German army. Sometimes it was Gestapo.’ (The operators could tell this by the way the letters were sent.) ‘And oh God, it really upset us, that did.’

The messages were taken down in ordinary English letters in blocks of five, which in themselves were strings of meaningless letters. ‘But it was interesting in as much as we knew that we’d got to get it right. As I say, if we weren’t sure, we didn’t guess, we put a blank. And then these were sent to Bletchley, who then had to decode them. They were so clever, those people, really, really clever.’

By the time Noel was a qualified operator, the team at Bletchley Park had cracked the Enigma Code. She recalls the Enigma machine: ‘It was like a typewriter. But in addition to the Qwerty things, there was above that another keyboard with lights. At the beginning of the war, the Poles got hold of an Enigma Machine and passed it to our people. Otherwise I don’t think we could have done it. Also, one of our ships intercepted a submarine, and they were able to lift an Enigma machine, and a code book from the submarine’

Just Ordinary Girls…

‘We were so keen, and just ordinary girls. And yet, this secret never got out. It was wonderful. I’m really proud of the fact that we did that work, and that we kept the secret. And all through the years, I’ve kept in touch with people that were with me then, and there are still a few of us left. You really felt you had done something towards the war effort. What you had done, mattered.’

Further information:

Links to other accounts by other women who trained as WW2 Morse operators

Linda Battle and Margaret Crook

‘The Gentle Sex’ (1943) can be viewed on Amazon Prime Video. It’s surprisingly interesting and entertaining, following the fictional progress of seven recruits, but showing different sides of genuine training in the ATS. The table tennis clip comes about 21m 30s into the film – and lasts for about 3 seconds!

Other links to aspects of women’s war work:

Related Books by Cherry Gilchrist