Upriver – the other end of town

To round off my current series of blogs about Topsham, I’d like to take you on a wander heading out of town up the river Exe, towards Exeter.

Sir Alex’s Walk

This riverside path is far less popular than the Goat Walk at the other end of Topsham. Perhaps the warning sign gives a clue as to why this should be.

Apparently, this wasn’t always the case. Even as late as 1968, D.M.Bradbeer wrote, ‘This pretty riverside walk is much frequented on fine summer evenings, when it is pleasant to loiter on the bank and watch the fishermen at work with their nets, and the sailing boats criss-crossing on the tide’.

The vista from the path today, however, is slashed by the M5 motorway bridge, and the fishermen are gone. Seine net fishing (stretching a net across the river) is now illegal, and in any case the practice had dwindled to a final few licensed boats as the salmon stocks had all but disappeared in the last twenty years. But the river bends, beds of rushes, overgrown landing stages, muddy creeks and boats in all stages of repair give this stretch of water an eerie charm. Nevertheless, it’s hard to imagine how so many strollers ever did manage to walk along this narrow path, as it’s like navigating a narrow Devon lane where you need to keep an eye out for passing places.

Rats, robberies and the scenic route

Before we get to the path though, the walk first takes us down Ferry Road, passing the Recreation Ground on the left hand-side. With its children’s playground and open grassy spaces, the ‘Rec’ is well-used in a town which doesn’t have all that much public land for community use, apart from the Goat Walk fields which I described earlier. The Rec might look rather flat and featureless, and that’s because it is largely an artificial plot, created on land reclaimed from the marshes. This happened over the years by very pragmatic means, since the site was used as the town rubbish tip.

In his memoir, John Willings (b.1923) recalls how in his boyhood the site was still evolving and was certainly what we’d consider hazardous today. At one end there were the Lime Kilns where ‘children used to play in and out of the caves which, even when empty, had plenty of lime dust on the walls and floor’.

Below is another similar type of work, ‘The Lime Kilns near Topsham on the Exe, Lympstone and Exmouth in the Distance’ by William Traies (1789–1872)

I searched for more information about Topsham Lime Kilns, and lime kilns in general. There were several sets of kilns around the town, where limestone was calcinated at high temperatures to produce quick lime. This was used for making cement, and as a soil improver in agriculture. Stone-built kilns left to fade into gentle ruins appealed to artists of the 19th century, as a romantic backdrop, as these paintings show.

But they could also be the scene of high drama. On Nov 27 1908, The Western Times reported that a daring robbery had taken place at the Topsham lime kilns situated near the River Clyst. A young man, named Leonard Johns, who was employed at the Odam’s Manure Works nearby, had just been to the bank, and was walking back with a bag containing £35 for the payment of the company’s weekly wages. ‘His assailant sprang upon him suddenly from tunnel in the old kilns, and, throwing a sack over his head, stole the bag and made off on a cycle towards St Mary. Our picture shows the boy Johns with the bag, and a well-known amateur actor who, to enable the scene to be reconstructed, impersonated the character. The masked robber is still at large.’ Does this grainy photo perhaps show one of the earliest ‘Crimewatch’ re-constructions? Later, the empty bag was found under the bridge at Winslade Park.

Returning to the lime kilns at Ferry Road, these would certainly have been a potential health and safety hazard for the children who played in them, both because of any residual heat and the very real possibility of the lime dust irritating or even burning the skin. The Wikipedia article which cites this risk also contains the surprising information that we may be eating it in our bread and cakes: ‘It is known as a food additive…as an acidity regulator, a flour treatment agent and as a leavener. It has E number E529.’

If Topsham children of the 1920s and 30s survived their encounter with the lime kilns, they could skip a little further along a rough track, (now the continuation of Ferry Road) to watch Mr. Punch Miller driving his horse and cart full of rubbish down to the tip several times a day, fulfilling his role as town dustman, and little by little building up the land which would become the playground of their future grandchildren.

In John Willing’s day, it was still very much a work in progress. Sport and rodents flourished together: ‘Enough of the wasteland at the “Rec” had been recovered, levelled and laid with turfs to provide a football pitch, which became waterlogged after every spring tide – and a part for swings and see-saws. Most of the area was still an ‘open’ dump where flocks of screeching gulls would pick at garbage and dozens of rats would scurry among the rusting tins and decaying waste. At one time the rats became so numerous that a hunt was organised which turned out to be a great sporting event for the town. The local fire brigade had been called in to pump water down the rat holes and flush out the rats who were than chased by packs of dogs and men and children armed with heavy sticks. Over 300 rats were killed…’

At the end of the Rec and beyond what is now known as ‘the dog walking field’, Sir Alex’s Walk begins in earnest, winding its way past the gardens of the houses built on higher land in Riverside Road. This is where D. M. Bradbeer’s vision of a ‘pretty riverside walk’ begins to hold good.

Again, John Willing lights up the less pretty realities when he recounts his cycle ride along the highest and narrowest section of the path. His father had given him a hand-me-down, heavy old bike, and John was determined to take it out on what was probably the most unsuitable track in the town for a trial run: ‘Being rather unsteady on my new acquisition I accidentally rode right over the edge and landed in the thick oozy mud – bike and all! I had to wade along the mud dragging my bike until the bank became low enough for me to clamber out. Covered from head to foot in the black stinking mud I dare not go back along the path where lots of people were taking their Sunday evening stroll…So I went on to the Newport fields and hid there until it became dark!’

On the right Retreat House comes into view, a much more beautiful landmark than the motorway bridge which is now alarmingly close by. Retreat House is a grand mansion re-modelled in the early 1790s by Sir Alexander Hamilton, merchant and High Sheriff of Devon. Earlier in the 18th century, it had housed French prisoners taken in the Napoleonic Wars As you may guess, Sir Alex also gave his name to the walk. The name has been modified in popular use, and sometimes still appears on maps as ‘Serrallick’s Walk’. Sir Alex was apparently knighted simply for congratulating King George III on surviving an attack by a madwoman who tried to stab him.

Beyond here, it looks at one point as though the path ends in a sharp drop, but when you get closer, if the tide is low enough, you see a set of steep, muddy steps leading down to a concrete path which continues forward, skirting the Retreat Boatyard. This is a fully working yard with expert boatbuilders.

And this is as far as I’m going up the river today, although you can continue beyond the bridge, skirting the Newport Homes site and heading…well I don’t know how much further! One day I will find out.

Names of the River

I’d like to end though with a mention of the old names for parts of the river, which have their own mystique. These were used not so long ago by the seine-net fishermen, as useful markers, guides to the spots to be fished: Clock, Black Oar Hard, The Drain, Cupboard, and Ting Tong, for instance, refer to places further downstream, but perhaps there are corresponding names for this upper stretch of river too? Please do leave a comment if you know of any!

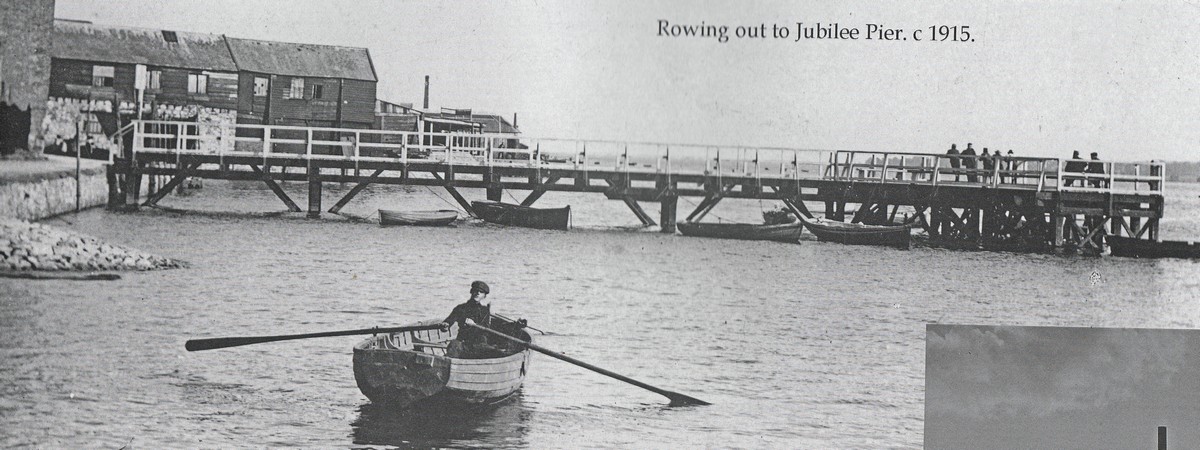

I’d particularly love to know where the name ‘Ting Tong’ comes from. There are Inner and Outer Ting Tong Lanes a few miles away in Budleigh Salterton, but I’ve found little clue about their origin, apart from the fact that Ting Tong means ‘a little crazy’ in Thai. Wikipedia suggests: Possibly related to Thing (assembly)#Viking_and_medieval_society’. I can’t see an assembly being held in or on the far side of River Exe, but who knows? My Halliwell’s Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words (excellent for Call My Bluff party games!) is silent on ‘Ting Tong’, but does have ‘Ting Tang’ as meaning ‘the saints-bell’. The ferry from Topsham across the Exe used to carry monks heading from Sherbourne Abbey to Buckfast Abbey and points west in medieval times. Ting Tong lies on the opposite side of the river from Topsham, not too far from the present ferry dock, so perhaps the monastic travellers would ring the bell to alert the ferryman when they needed a return ride?

References

A History Little Known: A Topsham Childhood of Yesteryear John Willing (1984)

For details of Retreat House: Topsham: An Account of its Streets and Buildings, Caroline Obussier & contributors (The Topsham Society, revised edition 1986)

River names and map in Talking About Topsham, Stories of the Town Recorded by Sarah Vernon (2007)

Topsham Museum is closed until Spring 2021, but offers an excellent ‘Walking Trail’ map, which you can download here. The Museum is staffed by knowledgeable volunteers who may be able to help with individual enquiries too, about the history of the town and its families.

All photos except illustrations, or where stated, are by Cherry Gilchrist

You may also be interested to read: