This article was first published in the American magazine ‘Russian Life’in Nov/Dec 2001. It was based, at that point, on my nine years of travelling to and from Russia, investigating the art form, staying in the village of Kholui, and running Firebird Russian Arts in the UK. (A busy time!) Now, nineteen years later, of course much has changed. The Western market for buying lacquer miniatures has almost dried up, and many artists have switched to painting icons and commemorative panels, as this article in the New York Times illustrates. (NB – this otherwise excellent article is not always accurate on history or painting techniques!)

Everything about the history and style of the art form still stands, however. I hope that in time, the lacquer art painters will profit better from their creations, and find a market for the traditional boxes once again. One issue is the sheer time-consuming nature of creating them; as the Russian cost of living rises, and the differential between this and the West diminishes, it’s almost impossible for buyers to compensate the artists adequately for their skill and work. Money for commissioning icons, however, can be found more readily.

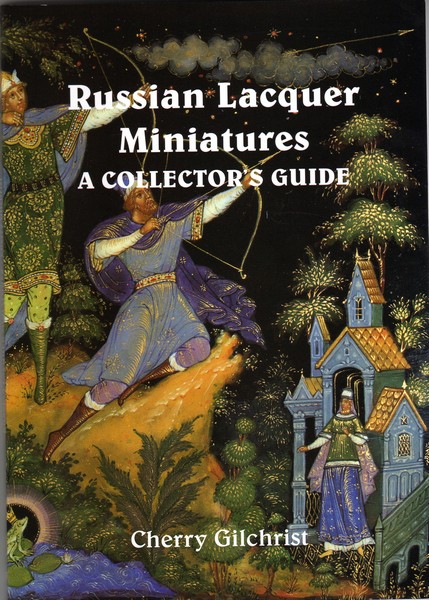

Please note – It’s extremely hard to photograph Russian Lacquer Miniatures well, since they are tiny, shiny and convex! Any gleams on the photograph are from where the light is catching the lacquer polish.

The article begins with an account of the scene that I described in my earlier post, ‘The Russian Diaries’.

The road to Kholui passes through stretches of open meadowland, brushing the edge of the forest, and traversing marshy tracts until it swings around the last sharp bend and meets the broad River Teza. This is the end of the road. The silver sign of the Firebird welcomes the occasional visitor. The fine, but crumbling, church singles the place out as one of historical importance. Substantial brick-built houses along the riverbank indicate that once rich merchants lived and traded here. The other houses in the village are traditional brightly-painted wooden izbas, with carved fretwork around the windows and eaves.

But this is no typical Russian village: of its 1800 inhabitants, 300 are artists. Kholui’s roots as an artistic community stretch back to the thirteenth century. For hundreds of years, it was also an important trading centre. And, along with three other villages – Palekh, Mstiora and Fedoskino, it is now home to a unique art form, the Russian Lacquer Miniature.

The quality of the Russian Lacquer Miniature is widely-known around the world, but even the average Russian knows very little about the art form. In Russian cities, cheaply-painted boxes are sold to tourists for a few dollars as ‘Lacquer Miniatures’, and in the States, many people erroneously call them ‘Palekh boxes’. Anyone can admire and enjoy a genuine lacquer miniature, but when you understand more about its history and the work that goes into it, then you truly begin to value it.

The history of the Russian Lacquer Miniature can be traced back to Russia’s ancient past, yet it is a comparably young art form. It looks timeless, but was only fully established as a genre in the 1920s and 30s. There are two distinct chapters in the history of lacquer miniatures.

In the 13th century, the village of Kholui, and its neighbours, Palekh and Mstiora, were icon-painting centres, founded by monks who fled the Suzdal area to escape the Tartar-Mongol invasion. They made their way into remote forested regions about a hundred miles to the east, where they established three separate settlements. Over the course of the centuries, these three villages trained generations of icon-painters. The names Palekh, Kholui and Mstiora became synonymous with schools of icon-painting, and their icons can often be found in museums and auctions today.

The icon-trading attracted commerce and fairs and markets arose. Kholui, now the quietest of the lacquer miniature villages, was once the liveliest and probably the wealthiest. Major fairs were held there at least five times a year, with buyers and sellers arriving not only from far-flung corners of Russia, but from abroad. Cloth, furs, fish, ‘lubok’ prints and anything and everything was sold here, along with the icons. Drunkenness, merry-making and quarrels abounded. One deep pool on the edge of the village is still known as ‘Turk’s Lake’, into which, it is said, a Turkish trader was hastily tipped after one quarrel too many. Old coins are regularly dug up in Kholui gardens, and the fair still just about lives on in the memory of old folk, though it was suppressed in the 1930s.

The trade in icons fell into sharp decline at the end of the nineteenth century, partly because mass-produced printed icons were cheap and widely available. After 1917, religious painting was discouraged, putting the remaining icon-painters out of a job. Officially, icon-painting was now defunct. Unofficially, the tradition was carried on secretly; the former director of the Kholui lacquer miniature workshop said he used to tip off the artists when official visitors were coming, so that they could hide any icons in progress.

The second chapter in the evolution of the lacquer miniatures as an art form came after the Bolshevik Revolution. Dedicated artists who remained cast around for something into which to channel their talents. They tried painting carpets and china, without great success. Then, in Palekh, an artist called Ivan Golikov began to create the first lacquer miniatures. The miniature form actually sprang out of the icon tradition, since icons often contained a border of miniature paintings around a central subject.

But now, instead of sacred themes, Golikov took the age-old legends and fairy tales of Russia for his subjects. He retained the use tempera, egg-based paints, and much of the icon style. In particular, the richly-coloured, gold-ornamented icons of Yaroslavl served as inspiration, their horses and chariots, robes and palaces already almost suggestive of fairy tales rather than religious themes. But, significantly, Golikov changed from using wood to lacquered papier mache as a base.

This is where Fedoskino, the fourth village comes into our story. Fedoskino artists argue that they were the first school of Russian lacquer miniature painting, since their workshop was originally set up in 1798. It was the brainchild of a merchant called Korobov, who realised that he could sell vast quantities of snuff boxes if he could make them both cheap and attractive. Many people could not afford the snuff boxes made of ivory, jade or other precious materials which were in vogue at the time. Using a process which he discovered in Germany, Korobov began to produce little boxes of papier mache. He employed artists to decorate them, and he finished them in lacquer to produce a very durable and attractive finish. Over the course of time, many other beautiful but functional types of boxes were produced, as tea caddies, card cases and so on. And, since Fedoskino lay just north of Moscow, it was well-placed to serve the fashion-conscious clientele of the city.

The Fedoskino artists painted in oils from the start, and took their style from mainstream art, which at that time in Russia was very similar to Western art. They did begin to introduce a distinctly Russian flavour however, painting troikas and village scenes, and girls in national costume. They also began to concentrate more and more on the quality of the painting itself; it was no longer enough just to decorate a box. The workshop, a highly successful venture, subsequently passed into the hands of the Lukutin family, and remained as such until it became a co-operative in 1910. It has always retained its distinctive style, which is also now often characterised by an underlay of mother of pearl, or gold leaf. This gives the miniature an iridescent sheen, and an inner glow, and is particularly effective for bringing to life snow scenes, sunlight, and silken draperies.

Back in Palekh in the 1920s, Golikov gathered a small group of artists around him, and this founding group set the Palekh style securely in place for succeeding generations. It is, not surprisingly, very iconic, with beautifully detailed faces, and elongated figures poised in dignified stances. It consists of vivid colours, often including brilliant reds or blues, but always used with restraint on a background of black lacquer.

All the lacquer miniature schools generally use black for the outside of the box, and red for the inside, though they paint over the black to a far greater degree than the Palekh artists. Red equals life and beauty in Russian colour symbolism, and the black expresses both the mystery and the sorrows of life. The black background helps the vivid miniature scenes appear as if they are floating in another dimension of time and space, drawing us into the intense world that they create. The gold of the delicate ornament, used to highlight detail and provide a decorative border, is a symbol of eternity. This trio of colours – red, black and gold – also forms the basis of colour in other Russian folk art too, especially in the lacquered wooden ware of Khokhloma.

Kholui and Mstiora followed Palekh into the painting of lacquer miniatures in the 1930s. There was some rivalry between the villages, as each was eager to define its own status, and over the course of the years all three villages have developed very distinctive styles and outlooks. Kholui is dynamic, colourful, relying on contrast and a depth of perspective, and it often contains superb natural detail. Kholui artists today show remarkable creativity, especially the talented 26 or so members of the Kholui Union of Artists. Mstiora style is dreamy, with delicate, carefully-graded colours, and usually all of the background is painted over. Mstiora style needs a different eye; there is often less detail than in Palekh or Kholui painting, but the overall effect is wonderfully harmonious.

So despite the early start in Fedoskino, the genre of the Russian lacquer miniature with its four schools only really came to birth in the middle of the twentieth century. It remains a very Russian art form at its heart, with subjects drawn from fairy tales, historical legends, Russian landscapes and architecture, and festivals and scenes from old village life. The artists meticulously research their themes, if they are not within living memory. Sometimes flowers, animals, portraits, and non-Russian themes are painted, often with stunning results – but stray too far or too often from the Russian flavour, and the art weakens.

The artists of this genre go through a thorough training lasting five years. Each of the four villages has its own art school, and outsiders are welcomed as well as children born and bred in the village. There is healthy competition for spaces, with about four or five applicants vying for each slot. In general, students do not pay tuition, though schools are beginning to offer a proportion of fee-paying places simply to survive. Students must show not only a talent for art, but also must also have excellent eyesight and good general health.

Contrary to popular belief, the lacquer miniature artists’ eyesight does not typically deteriorate more than other adults, despite the fact that they carry out such incredibly detailed work. (Painting fine gold ornament is especially taxing and is done with the finest of brushes.) They are taught so well that they work more with mind and hand than with the eye .In fact, lacquer miniature artists prefer not to work with magnifying glasses, as they like to see the whole of their composition at once. But students don’t spend all their time in such concentrated work; they are also encouraged to work in charcoal, oils and watercolours, to draw from life, and to study the history of art as well. Much of their miniature training is acquired by copying from examples, so that they learn in a very disciplined and structured way. For their diploma, however, they must produce a completely original composition.

It is important to understand that lacquer art does not depend entirely upon original compositions. The word ‘copy’ often has negative connotations in Western minds. But this does not mean something slavish and mechanical; it is rather the chance to re-create the work of a master. This approach is common in Eastern art as well as in icon-painting, where the artist does not have to strive to be original. Some artists at the pinnacle of the profession only paint originals or ‘author’s works’ as they are described in Russian. Others will only ever paint existing subjects, drawing from a range of designs and repertoire. Altogether, this forms the body of the art, which has a life of its own and a strongly collective element. Even the most ‘original’ artists usually meet in council in their union or co-operative to discuss their works – and criticisms are certainly made, especially if other artists feel that new compositions are spoiling or weakening the tradition. Artists who leave and settle elsewhere are rarely able to keep up the quality of work; the members of the collective rely on each other, the spirit of the art, and indeed the ‘spirit of place’ of their village.

Some years ago, the Soviet government tried to artificially create a fifth centre of folk art in the industrial city of Lipetsk. Artists were tempted to re-settle there with promises of modern flats, bathrooms and running water (luxuries not available in the ‘izba’). Sadly, the experiment was a failure; nothing new or creative has emerged from Lipetsk, and it now turns out low quality miniatures for the tourist market. The artists who moved there could never return, and gradually they lost both their individual creativity and the vital link into the main body of the art.

The four lacquer miniature villages are all quite individual, set in beautiful countryside which is a source of inspiration to the artists. Intense sunsets, deep forests, spring floods, fall harvests and winter snows all fuel their imagination. The artists are rooted in the traditional life of the Russian countryside, with seasons for potato-planting and mushroom-gathering, berry picking and fishing. And, like most rural Russians, they have to make do for themselves, mending their homes and tending the vegetable plots. Women and men are both in the ranks of artists, sometimes even working as a husband and wife team, taking turns minding the children while the other one paints.

Meanwhile, more than ten years after the lifting of state controls, lacquer miniature artists find the situation for selling their art to be quite fluid. Though some regret that they are no longer as financially secure as they were, most prefer the creative freedom: they are no longer tied to a production quota, and can work as and when they please.

The four original state-run studios, one for each village, still function in various disorganised stages of privatisation. Some artists work there on salary, while others are members of co-operatives or unions. Still others go it alone. Much depends upon their contacts, and the selling network that they find their way into. Thus, it is not always the best artists who are the richest.

The domestic market for this art form is weak, although recently record prices for lacquer miniatures have been extracted from tourists in St Petersburg. The plain fact is that most miniatures find their way West; in Russia, only corporate customers such as banks regularly buy them. Once, museums were queuing up to buy the best lacquer miniatures, and none of the real masterpieces ever left the country. Now the museums do not have the funds for such purposes, and Russians with money would rather buy consumer goods rather than art.

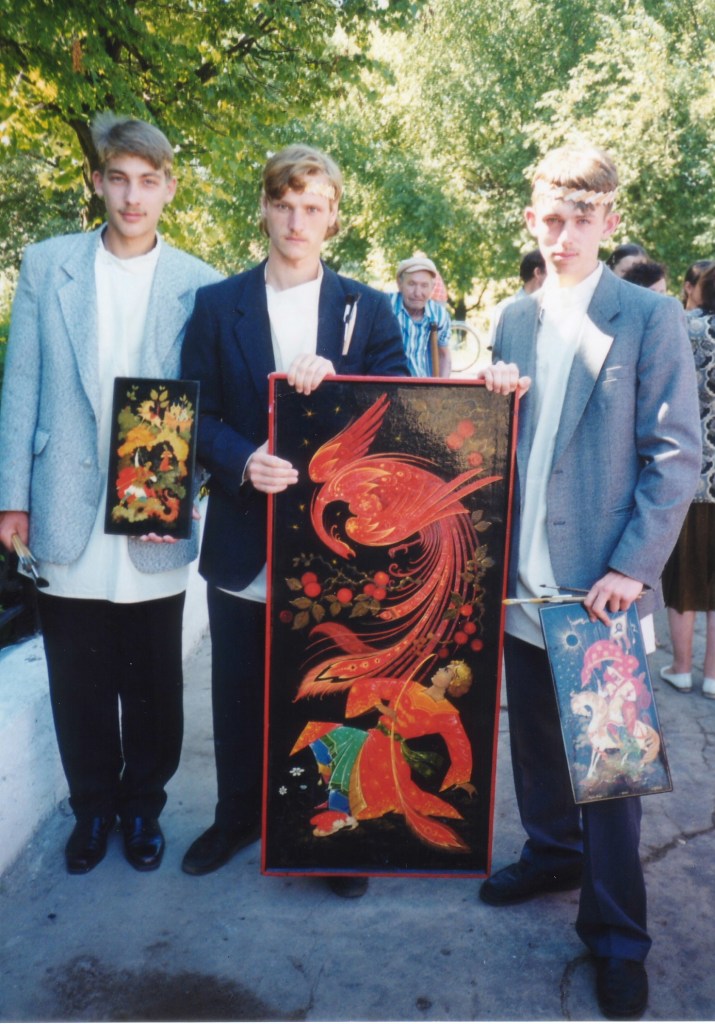

This dissolution of control over production brought other challenges as well. In Fedoskino and Palekh especially, artists have split into many groups, some of them now in a difficult relationship with one another. But on the whole, genuine aspiration and honesty is still at the heart of the tradition, and the studios still work with dogged persistence in extremely difficult market conditions. Each village has its own stupendously good museum, and exhibitions, celebrations and jubilees are common excuses to get together with artists and colleagues from the other lacquer centres and party at great length once the official speeches are over.

It is worth noting that the making of the papier-maché and the lacquering and polishing of finished work is actually not done by the individual artists. Rather, it is done by another team of craftsmen, who are skilled, but who do not enjoy the status level of the artists. It is an interesting process in its own right, involving just the right type of cardboard, from which the papier-maché is made, the ‘slow-cooking’ of the papier-maché for two or three months, and painstaking lacquering and polishing. Three or four coats of lacquer are applied before the artist begins painting the miniature. Afterwards, between seven and twelve coats must be applied, and each one dried and polished to achieve the right finish. The lacquer has to be made to just the right formula; untrained city artists producing ‘souvenir’ boxes often slap on a couple of coats of floor varnish, and hope for the best. This will usually crack up within a couple of years, whereas properly lacquered works will survive, with only a little dulling, for centuries.

No genuine lacquer miniature is complete in less than three months from start to finish, and many will take a year or more. The simplest design will take the artist several days to paint; the most complex more than twelve months.

As the basis for the lacquer miniature, the traditional form of the box is still the most popular. Yet, as the art became finer and finer, so the utility of the box was largely forgotten, and the miniatures became collectors’ items in their own right. Although the art of the miniature is the main focus, a miniature on a box is still evocative, like an exquisite treasure chest. Some of the old functional shapes have been retained, such as the ‘inkwell’ and ‘cigarette case’, but for decorative interest only. Artists often paint plaques and panels as well, and brooches have gained in popularity in recent years. They also occasionally paint wall panels and frescoes – on a completely different scale of course – and lovely examples of these can be seen in the restaurant in Palekh, and in the children’s home in Mstiora.

It is often asked whether there is a Persian or Moghul influence in the miniatures. The artists themselves deny this, and it is more likely that there is a slight similarity of style, simply because of painting lively scenes on a small scale in vivid colours. Once at a British art exhibition, Uzbeki miniaturists were painting in the next tent to Russian lacquer miniature artists. A British interpreter was getting very heated as she defended her Uzbeki artists against the supposed crimes of their ‘thieving’ former overlords, claiming that those Russians next door had ‘stolen’ the tradition from the Uzbeks. The Uzbeki Minister of Culture, who happened to be present, gently put her right. He noted that they had actually sent some of their own Uzbeki artists to Palekh to train in miniature painting and production, having lost their own indigenous tradition some time back. With the help of this input from Russian artists, they are now trying to re-create their own style using Russian technique as a basis.

The creative potential of the Russian Lacquer Miniature can be tapped in unexpected ways. But at its heart, it remains a uniquely Russian art form, its little boxes dispatched across the globe as messengers from the soul of Russia, carriers of her magical tales and traditions.

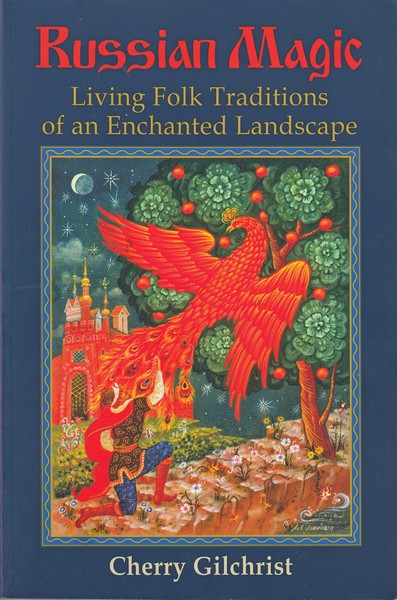

Related books by Cherry Gilchrist