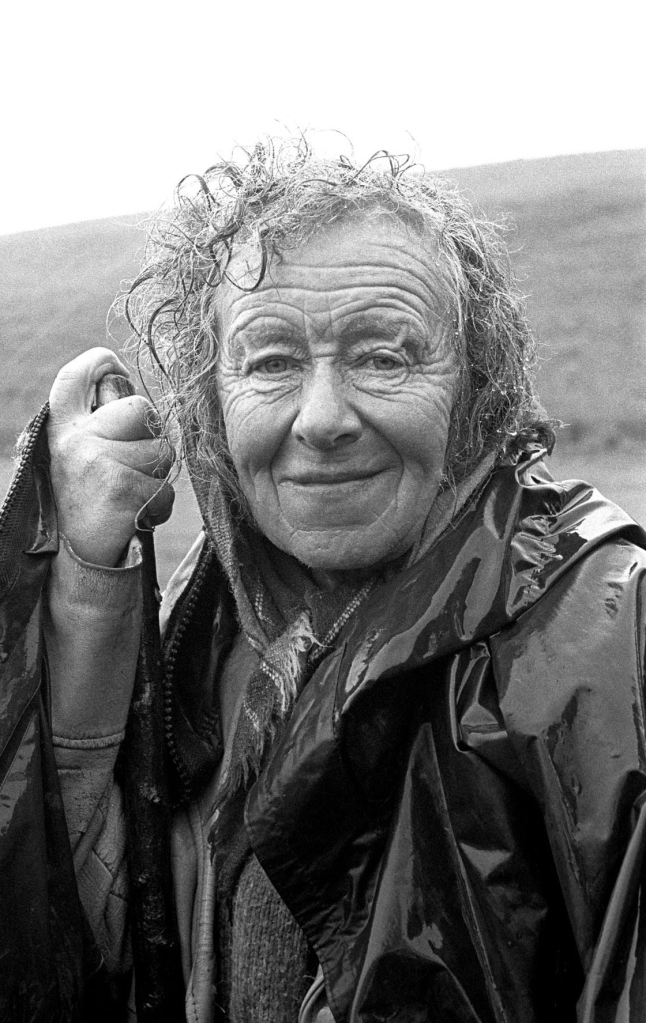

This is the first blog in which I’ll celebrate ‘Wild Women of Words’ – women who lived unconventionally, close to nature, and wrote about their own special pursuits. Here I’ll introduce you to Hope Bourne, whose writing was primarily about the wild landscape that she lived in.

A Personal Recollection

In the 1980s, when I was living near Dulverton on Exmoor, we used to buy the West Somerset Free Press newspaper. It was an all-purpose local newspaper, with the kind of headlines that didn’t shake the world. (The one which sticks in my mind was: ‘Rainfall breaks all records!’ Amazing, I thought – but reading on, I discovered that for the first time ever, it had been exactly ‘average’ for the last month. And ‘Hit and Run Driver’ was the villain who’d left a slight dent in another car and not left their details. But perhaps we should be thankful for such mild dramas in local life.

However, the newspaper also contained something unique – a column by one ‘Hope Bourne’. Was it a pseudonym, I wondered, as ‘Patience Strong’ had been a generation earlier, a pseudonym for Winifred Emma May who wrote morally uplifting, often cringeworthy poems for magazines. But I soon realised that Hope Bourne was indeed the genuine name of a woman who lived a very unusual life, immersed in the wild nature of Exmoor. At this time, Hope would already have been in her 60s. She lived remotely, more or less what we’d now call ‘off grid’, and walked miles over the wild moorland every day, sometimes shooting and fishing to catch her food. She was very knowledgeable about history and landscape, and not afraid to speak out from her own values, whether they were the popular ones or not.

I learnt more specifically that she lived alone in a caravan on the site of a burnt-out farmhouse at Ferny Ball in the wilds of Exmoor. She had no transport, but would regularly walk the four miles to Withypool and back, to pick up essential shopping. She observed the changing seasons and the life of the moor in detail, writing and ruminating over the changes and sometimes painting or drawing what she saw – she was a skilled artist who had had professional commissions in her time. All this was the basis for her regular newspaper articles. And she shot rabbits for the pot, a firm believer in the old ways of the countryside. In this way, she was somewhat like the poet Ted Hughes, who hunted and fished as part of his immersion in the natural world, not backing away from the realities of where food comes from.

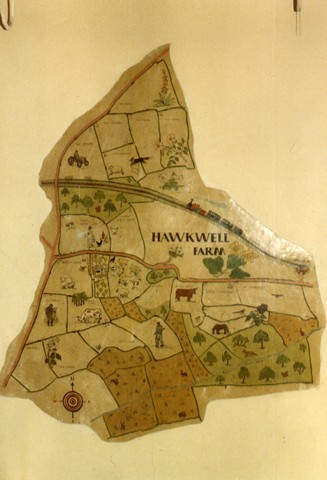

At this time, we lived in an old Devon longhouse, called Hawkwell Farm. It was no longer a complete farm with all its land, but we still had 10 acres – enough for me to fulfil a dream of owning a horse (or two), and keeping chickens, something which I’d loved as a child. Hope kept bantams around her caravan pitch in the abandoned farmyard. And according to her newspaper column, these bred freely and she often had more bantam chicks than she knew what to do with. So I plucked up courage and wrote to her. We could offer a home for one or two, if she liked?

Hope did indeed like the idea. She had a couple of spare bantams looking for a good home. She invited me over to visit her and I in turn invited her to come back in the Land Rover with me to lunch, and see where the two bantams would be living. She accepted with alacrity – she was keen to see corners of Exmoor that she hadn’t visited before.

All this happened forty years ago, so my memory is a little hazy, but I remember being somewhat shocked when I drove up to Ferny Ball, to see the ruinous state of the farm surrounding her caravan. And we chatted easily – I was left in no doubt that she was a sharp-minded, lively woman with strong views. I do remember in particular her opinion of the stag hunt on Exmoor, already contentious at that time, and later banned. ‘You see,’ she said, ‘I view it as one of the last remnants of medieval pageantry.’ I had never thought of it that way before, but I mused on her perspective. The deer do need culling, as they have no natural predators such as wolves in this man-managed landscape, and the debate is usually over whether it’s better to hunt or shoot them. There are many articles about deer on Exmoor, and their welfare, such as https://wildaboutexmoor.com/exmoor-deer/ and, in my old friend the West Somerset Free Press. But for Hope to see it as part of the old ways of the countryside, and its rich traditions, certainly gave food for thought.

Hope had arrived on Exmoor as a child. She was born in Oxford in 1918, the illegitimate daughter of a school teacher; her father was an Australian soldier, who she never met, but thought that she probably inherited her ‘love of guns and horses’ from him. Hope and her mother moved to Hartland in north Devon in 1927, and eventually in 1951 to a cottage on Exmoor. With just a short absence after her mother died in 1955 (when Hope tried out life in Australia on a sheep farm), Hope then lived on Exmoor for nearly fifty years. It was a singular life, but not a reclusive one. She loved her life alone, but also welcomed company – remembered by others as a kind, helpful woman. She often helped out on the farms where she was skilled with haymaking, harvest, and working with cattle and sheep. Horses were also her love, and she created beautiful paintings of the Exmoor ponies, who roam semi-wild there.

For many of these biographical details, I’m indebted to Chris Chapman for his video ‘How many people see the stars as I do?’ You can watch a trailer for the film (see below) and purchase it from Chris Chapman directly, an account of Hope’s life and his friendship with her. I’m also grateful to Chris for permission to use his stunning portrait of Hope to open this account.

The Bantams Arrive

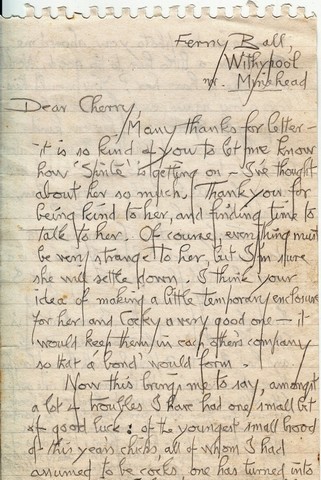

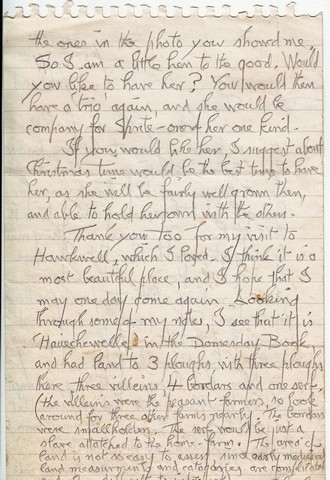

Hope and the ‘banties’ thus arrived at Hawkwell, and we gave her lunch and chatted – I wish now that I’d recorded or noted down more of our conversation. Sprite, the female bantam, along with ‘Cocky’ (a male surplus to Hope’s own flock) settled down nicely with our assorted flock of free range hens, and a few more bantam companions. Then a little later, I received a further letter from her, offering me another growing bantam.

Dear Cherry,

Many thanks for letter – it is so kind of you to let me know how ‘Sprite’ is getting on – I’ve thought about her so much. Thank you for being kind to her, and finding time to talk to her. Of course, everything must be very strange to her, but I’m sure she will settle down. I think your idea of making a little temporary enclosure for her and Cocky a very good one – it would keep them in each other’s company so that a ‘bond’ would form.

Now this brings me to say, amongst a lot of troubles I have had one bit of good luck: of the youngest small brood of this year’s chicks, all of whom I had assumed to be cocks, one has turned into a pretty little lightish-coloured hen, like the ones in the photo you showed me. So I am a little hen to the good. Would you like to have her? You would then have a trio again, and she would be company for Sprite – one of her own kind.

If you would like her, I suggest about Christmas time would be the best time to have her, as she will be fairly well grown then, and able to hold her own with the others.

Thank you too for my visit to Hawkwell, which I loved. I think it is a most beautiful place, and I hope that I may one day come again. Looking through some of my notes, I see that it is ‘Hawechewelle’ (?) in the Domesday Book and had land to 3 ploughs, with three ploughs there, three villeins, 4 bordars [smallholders] and one serf, (the villeins were the peasant farmers, so look around for three other farms nearby. The bordars were smallholders. The serf would be just a slave attached to the home-farm. The area of land is not so easy to assess, since early medieval land measurements and categories are complicated and often difficult to interpret.

Hoping to hear from you again before too long,

Hope L. B.

After that, I didn’t meet Hope again, which is much to my regret now. Our own country dream (more romantic and less committed than Hope’s way of life) came to an end when we moved up to Bristol in 1987, and we re-homed our menagerie. Schooling for the children, work in London for my husband, my growing involvement in singing early music– all these prised us out of our Exmoor idyll. Plus it was very hard work. We were not made of the stern stuff that Hope was.

Her letter to me, below:

I kept up with news of Hope through mutual friends from time to time, and eventually heard that she had had to give up her ‘wild’ existence. She was getting older, less healthy, and no richer either – the Poll Tax imposed by Margaret Thatcher, money to pay simply for being alive, was one of the final straws. She had been a fierce resister in refusing all State aid for all those years, and now she was to be penalised for this. As we now know, this hugely unpopular tax was abolished a few short years later – but by then it was too late for Hope. She thus moved into sheltered accommodation with the financial assistance of kind friends.

Hope’s Legacy

I have three of her books on my shelf: Living on Exmoor, Exmoor Village, and Hope Bourne’s History of Exmoor. Apparently Living on Exmoor was put together out of scraps of paper, packed up in a cow cake bag and sent on spec to the publishers! Luckily, they recognised it as something quite unique, and accepted it. Her writing can be a little on the effusive side, but I’m not surprised that it does sometimes go a little over the top – it is astonishing how she manages to sustain descriptions of nature and the landscape page after page. There are some truly beautiful passages, marked with sharp observations. From the chapter on May, therefore, in Living on Exmoor, which is particularly appropriate to the moment that I’m writing this, with the first of May in a couple of days’ time.

Everywhere the beech has burst into such a glory of living green as bewilders all the senses. Translucent, soft as silk, delicate as fluttering wings, holding the light in showers of pure green-gold – the beech leaves break over the harsh moorland landscape like a benediction, like a voice proclaiming life. Over hill and combe, all round the fields and about the grey-roofed farms the green tide flows and tosses, life from the brown shucked bud, life from the dead wood, life reaching out to the mounting summer sun. How lovely is the beech! No foliage is there more delicate in spring, no leaves so fiery in autumn, nor yet any tree stouter to face the winter gales….Now I walk home in the evening hours, with all the sky an ocean of endless radiant light…and see the hills dissolve in molten space, and all the leaves, each one a green translucent thing, a green light against the light. The sun sinks down and is gone. The horizon grows dark with a line of wind-twisted beech marching along its rim, far off and distant like a drawing. The sense of space and distance is enormous, infinite. It is like looking at a country far off in space and time…The dark sky-line against the light seems to draw one’s soul…Suddenly all things seem possible, for one feels a power that is more than mortal all around. It Is an awareness that is something beyond all human understanding.

The hollow drumming of a snipe comes strange and vibrant in the silence. I turn through the first field gate int the twilight, and the last sound of the night is the croaking of the frogs like inane laughter in the labyrinth of the bog below.

Hope became an esteemed figure in the landscape during her life on Exmoor. In 1978, Daniel Farson made a film about her. She thus became a ‘star of self-sufficiency’ for a while, but didn’t enjoy the attention – she didn’t want to be seen as a ‘back to the land’ hippy, but empasised that lived her way ‘out of necessity’. She never had much money; her grandfather’s will cut off any possible inheritance from her mother.

Since her death, her renown has grown year after year, and she is now a legend. Regular walks for visitors are conducted down the tracks that she walked, she features in Exmoor exhibitions, and has become part of the heritage of Exmoor itself. Our lives only touched each other for a short while, but I’m proud to have known her, and wish it had been for longer. Exmoor itself is imprinted on my soul, and now that we’re back living in Devon, I try to visit it regularly again.

For another illustrated article about Hope, with further details of her life, and emphasising her contribution to understanding nature and our place in it, see ‘How Many People see the Stars as I do?’ in The Return of the Native, a blog about Landscapes of Literature, Art and Song.

Great post, Cherry. Very interesting. Thank you

LikeLike

What wonderful personal memories you evoke with this piece, of living and working on the edge of Exmoor for some 15 years (North Molton) – a mixture of ‘country dream’ and pragmatism on our part (husband and I). We moved there from London full-time in 1989 at a time when you soon became aware of Hope’s name. Later I worked for Halsgrove publishers who started to reprint Hope’s books, with great success. As a journalist who contributed regularly to Exmoor magazine, I hoped one day to meet her but I think I’d probably missed the moment as this would be late 90s. Exmoor left its imprint on my soul and though I now live in Cheshire – after a fifteen year sojourn in France – it is frustratingly just too far away to revisit lately. I miss it with an ache but those fifteen years are still bright in my memory and I will make it back. My love of beech just emerging, as it is now, was born of that time. The landscape inspired me to paint for a while and whilst writing an ill-fated book about Exmoor I became deeply fascinated by its history, standing stones and circles almost lost in the landscape, iron age hill forts, the ponies … you can almost feel Bronze-age ghosts flitting about bemused. What a perfect choice to start a blog about ‘wild women of words’ – I look forward to more.

LikeLike

Thank you, Debbie! I’m interested to hear that you worked for Halsgrove publishers, and the Exmoor magazine – a really excellent production. Yes, I feel that Exmoor is a magical place and fortunately I live close enough that I can get up there a few times a year. Your own book sounds interesting too!

LikeLike

thank you – I think I started writing for Exmoor mag for the wonderful Hilary Binding. At Halsgrove I worked with Steven Pugsley and Simon Butler. Unfortunately, I left for France just as my book was published and for various reasons it died the death but did garner a couple of nice reviews. In retrospect, happy days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely post Cherry. Hope’s description of beech trees and the landscape quite stirring. What a singular woman. Lovely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this fascinating piece Cherry – and I’ve never read anything quite like Hope Bourne’s piece that you quote – amazing! Beech trees grow abundantly on the tops of chalky hills like The Chilterns, We used to frequent a cottage near West Wycombe as children and I always found the experience of beech woods very particular. I didn’t know they grew on Exmoor, and, judging from the picture, they grow differently but still create those magical light-filled areal tissues.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John! Would they be growing on chalk in the Chilterns? That might make a difference. Exmoor is mainly reddish, loamy soil. Also the beeches were used a lot for hedging – sometimes the trees grow up from neglected hedges.

LikeLike