In the 1980s, our family lived near Dulverton on the edge of Exmoor, and we quickly made contacts across a broad range of people, both of rural and town origins, and from different backgrounds. Exmoor was a great leveller – our local ‘Lady’ (who shall be nameless) had a rather public affair with her builder, and hippie incomers (rather like us!) mixed happily with Exmoor dwellers who’d been there for generations.

One of our great friends was a farmer called Arthur Oakes. He came into my orbit because he was interested in astrology, which I was teaching at the time. Arthur was then in his early seventies, and one of the most open-minded, innovative people that I’ve ever met. He was born in 1908, and was brought up on a traditional mixed farm, in the days of horses to pull the carts and machinery. However, he turned to organic ways of farming before many people had even heard of it, and was an advocate for avoiding chemicals on the land, and using good husbandry and soil management instead. His memory stretched back a long time – as you’ll read in this interview, his memories of World War I were both sharp and painful. He was keenly observant in everyday life too, always noticing something to share and to laugh over if possible.

The family was not from Exmoor; it seems his father came from the Welsh borders to Norton Lindsey in Warwickshire, and that Arthur himself moved his family down to Exmoor during his own farming career. As a boy, he’d been to Grammar School in Coventry (which had to be paid for in those days – a struggle for his parents to afford) and he used to read everything he could get his hands on.

Arthur also came to a small group that Chris and I were running at the time, called ‘The Journeyman’s Way’, an approach to self-development based on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. (for the background to this, please see ‘Soho Tree‘, a website which I manage with colleague Rod Thorn). He was one of our most regular and steady members.

In terms of social life, he and his family were a lively, jolly lot, and many was the evening we’d get a phone call at about 5pm, saying ‘Are you doing anything tonight? Come over and have supper! Bring the children.’ When we’d get to their farm at Howtown, near Winsford, there would be a merry gathering of a dozen or so people entertaining each other, kids of all ages charging through the house, and generous plates of food set out buffet style, provided by Arthur and Enid’s grown-up daughters Val and Deb. Everyone would mingle and chat until those with small children or farms to run would begin to rub their eyes and head for home.

I valued our contact with the Oakes family enormously, and at one point, when I was writing a book for schools on Life in Britain in World War One, and a companion book on Life in the 1930s, I interviewed Arthur about his experiences. Much later, I transferred the scratchy tapes to digital, as I still have them – and was recently able to send them electronically to Arthur’s grandson, so that they can be preserved within the family.

Arthur Oakes died in 1989, and I attended his funeral on a brisk spring day when the little churchyard was filled with daffodils. I remember him saying a few years earlier, ‘I was watching a stream flow into the river yesterday, and I thought, “This is what will happen to me when I die – a small stream joining the bigger river.”’

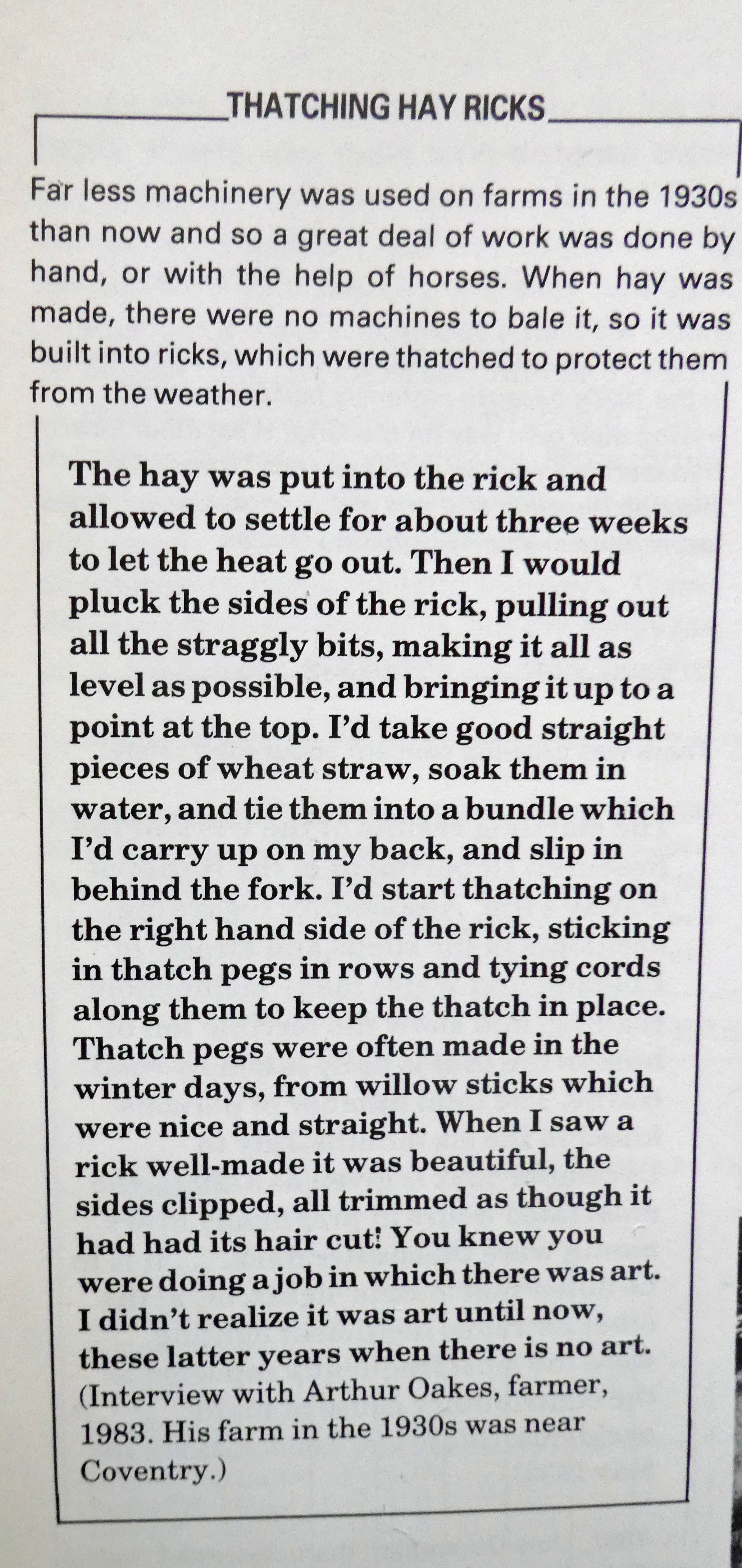

You can see Arthur above as he appeared in my book ‘Life in Britain in the 1930s‘ discussing how he thatched hay ricks – the photo of him also comes from the 1930s.

THE INTERVIEW

For this blog post, I’ve highlighted the extract from that interview which has always stayed clearly in my mind – Arthur’s personal memories of World War One, which shaped his subsequent views about war and poverty. It comprises the first quarter of the interview, slightly edited here for clarity, but with the aim of preserving Arthur’s voice. It’s been a moving experience, listening to that voice again.

World War One

CG Could you start off by telling me your earliest memories?

AO My earliest memories were really of the First World War. And the thing that struck me with horror, and has stayed with me ever since, was when the government, towards the end of this 1918 war –about 1917 – got into dire straits, and were requisitioning horses. They wanted them to go over to France and fight, and to pull the transport wagons and the ammunition. And I remember soldiers arriving in our farmyard and having all the horses rounded up and saying to my father, ‘We’re having that one, and that one, and that one.’ There were three that went, which were very much family pets. And one that was a carthorse. They just wrote out a chit to my father, and told him to take it somewhere or other to get his money. They said that the chit gave him the opportunity of having them back for free at the end of the war. Well, we never had them back at the end of the war – there wasn’t any end for those horses – only death.

I remember the soldiers taking our horses, leading them away, and my father leaning up against the wall in the yard and weeping over it. These two ponies were extra special, you know – he’d brought them from Wales with him. He’d used them – he’d had generations of them and bred them down, sending them to special stallions, and they were little workhorses. The ponies took them [Arthur’s parents] to market, they did the shopping, they did the shepherding, they pulled the food around for the sheep, and my father said, ‘I shall never see them again.’ And it suddenly struck me that there was no excitement in war, or any war, there was just misery. Then my brothers went [to war] and it really hit home. I wouldn’t have been very old then.

CG – How old would you have been?

AO – Eight. And up till then, the war had been an excitement.

CG – What had excited you about it?

AO – Well, it had been a total change – we hadn’t got young men working on the farm because they’d been called up. The usual razmataz of soldiers in uniforms, and blackouts too – but the things that were exciting to a boy who’d got pretend guns, suddenly turned into tragedy. And from then on, I feel now that I probably went into myself, because fear suddenly hit me. If they could take the horses, they could take other things that were my solid background, and things might begin to disappear off the road, as it were. It wasn’t long after that that the hay ricks did disappear, because they came to requisition hay to feed the horses on as well. I began to become aware that I was afraid of military dictatorship, military government.

It hit me too when I went to market with my brother in the holidays, to take some sheep along. He was about eighteen – he was ten years older than me –and there was a recruiting officer even in the market, who said to him, ‘What do you think you’re doing? You know you ought to be in uniform.’ And that scared the pants off him. And eventually he was in uniform. But that sort of thing was kicking the world from under me, kicking the solid world from under my feet.

The Armistice and aftermath of war

Arthur and his brothers worked hard on the farm – it was expected of them, and they would turn their hand to whatever jobs needed doing, whether roundingnup sheep, taking animals to market, or the carthorse to the blacksmith. Visiting the blacksmith was one of Arthur’s least favourite jobs, because the smith had a queueing system, and sometimes he had to wait in line the whole day to get his horse’s hooves and shoes seen to.

AO I think the next great step forward in memory was the Armistice, the bells were all ringing – what a relief! But even then, there were food difficulties. Very much so, because I think they didn’t get around to rationing until the war had ended. Although food stocks were fairly good – if you knew where to get them! I remember swapping bacon for Cheddar with the local vicar! I came down to him with a great chunk of bacon, on a bike, and he loaded me up with as much Cheddar as I could carry back. He’d landed a great hundredweight of sugar from somewhere, and so all these sorts of swaps were going on.

However, soon after that period my father went out somewhere – I was probably rising nine. Came home with the sweetest little pony from somewhere. which he picked up for a few pounds. He said, ‘Look here – you jump on its back, and if you can manage it, it’s yours!’ Of course. the blooming thing hadn’t really been broken in, but between us we managed it – it was only small – black, with a silvery mane, I still remember. That taught me to ride. And during that period – we kept it four or five years – I used to do a lot of work with it, driving sheep from A to B. I hadn’t got a dog, but this pony was as good as a dog – it really was a marvellous little thing.

But I also have the memory of it going, because hard times struck, really hard times. I came home from school one day and missed the pony – it had gone. I said, ‘Where’s Bess?’ and ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘bit of bad news – I’ve had to sell her.’ The rent day had come along, and she’d gone, you see. Those sorts of things knocked security out of youngsters. We had the rug pulled from under us, time after time.

CG – Now this was in Warwickshire?

AO – Yes, we lived close to Coventry at that time. However, he pulled enough money out of his hat from somewhere, and was able to pay for me to have a bit of education at the local grammar school. I used to cycle there as a day boy for five or six years.

Above: the pretty village of Winscombe, Somerset, where Arthur farmed when we knew him in the 1980s.

Below: Tarr Steps, the famous prehistoric stone bridge over the River Barle on Exmoor, where he had previously farmed and where his daughter Deb trained horses for re-enactment and film work.

The Depression Years

AO –It created the first socialism, that thirties did, really and truly, and the poverty had to be witnessed to be thoroughly appreciated and understood, because should they get out of work, which they did, I think it was a pound a week they got as compensation, to keep a family on. [This would compare to about £50 – £60 today.] And what on earth was it? They used to go out and get a rabbit, for which they’d get locked up if they got caught, and they’d pinch mushrooms.

My father got me so annoyed, because he couldn’t see the other side of the coin. These people, in his opinion, were not helping themselves. For instance, he sold a lot of trees off the farm he owned, for a second income He had a lot of big old trees and elms cut down – the trunks were taken away by horsepower to the timberyards, and the tops were left lying all around. And thinking he was doing these unemployed men a good turn, he’d say, ‘Well you can have a top, if you clear it up.’ But these poor men hadn’t even got the tools to work with! They hadn’t got the tools to work with. And he lost patience with them. His generosity didn’t go so far as to say, ‘Well, you borrow my axe’, or anything like that. He thought that somehow or other, they ought to have had one. He could not understand.

It wasn’t much better for his own men working on the farm. He was paying them £1.50 at the time, with a free cottage and free milk and free vegetables, practically feeding them as well. But they didn’t have much out-of-pocket cash. And the rule was that if a man broke his fork, for instance, it was deducted out of his £1.50. One poor old chap, he said, ‘Look, I can’t manage. I just can’t manage, you know.’ These sort of hardships were hitting me, probably turning me from Toryism to Socialism, really and truly. I can’t forget them, because there was real poverty, and real need, and real hardship. And I think if the men got condemned because they took ten shillings up to the pub and blew it on getting drunk, they were to be excused, because their life was a misery, to see their kids in need, and their wives driven frantic. These days it would end up in broken marriages and all sorts of things, but in those days didn’t because of necessity they had to cling together. The necessity just to live, to hang on. It was a horrible state of affairs.

The Wheel of Nature and Life

Arthur’s own family were never short of food, and always had a warm house, for which he was thankful. However, their farming fortunes were very mixed, and there were hard times like when his father couldn’t sell the wool from the shearing. Demand for produce varied hugely. His mother had her own small poultry business, which helped to keep them going, but nevertheless they were never too far from the bread line. But as Arthur said: ‘There was this feeling of self-sufficiency. We could feed ourselves on what we grew’. A traditional mixed farm, like the Oakes’s, could provide grain for flour, meat, butter, milk, eggs and vegetables. And although the overall picture Arthur painted wasn’t rose-tinted, he was at pains to point out that within farming itself, there was always the chance for renewal. The cycles of life and the land breed optimism, because the wheel always turns again:

‘Farming always seemed to be the remedy – however bad it was, there was always hope in farming. Spring comes along, and you plant a new crop, and you’ve got lambs, and you think things are bound to be better this year, because it’s going to be a bountiful year. And it very often was.’

Arthur’s departure

A strange thing happened when Arthur died. We knew that he’d got cancer – he was just over 80 by then, but it didn’t seem too serious or without hope for recovery. One Sunday afternoon, Chris and I drove to the Gower peninsula from Bristol. As we traversed some heathland near to the coast, I had the Ordnance Survey map open and noticed an interesting ancient site indicated on our right, called ‘Arthur’s Stone’. It turned out to be a single standing stone, and as we slowed down to take a look, I noticed a curlew standing close to the road, its proud, curved beak in profile. This gave me an eerie feeling. It was also an unusual bird to see, at least in our experience at that time. Then, after we got home, the phone rang, and it was Arthur’s daughter Deb, calling to give us news of his death. I have ever since felt that Arthur’s spirit was set free to bid us and others farewell. Look at his photo above, and you’ll see why the curlew’s beak seems so appropriate!

You may also be interested in other life stories of people that I’ve encountered:

Noel Leadbeater and the Secret Army

Thank-you for the honor of learning Arthur Oakes’ story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Arthur’s story really brings history to life. My grandfather joined the Hussars around 1910 and went from an impoverished south London background to learning how to ride and care for horses before the outbreak of war. He survived the conflict and seemed to have been very attached to his horse and I often wonder (having seen War Horse) where that horse came from and what happened to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This afternoon I am going to sit down and read all this so interesting . Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person