Discovering Colonel Edward Marcus Despard (1751-18030)

What are the chances of discovering an ancestor via a popular TV drama? Unlikely, I would have said, until it happened to me. Although I’m a keen family historian, with years of diligent research behind me, it was only through watching ‘Poldark’ that I found one of the most interesting, radical and unusual ancestors ever to grace my family tree. I had better say straight away that this ancestor was also hanged for treason. However, many believed that he was falsely accused, and new scrutiny has led to historians reclaiming him as a champion of human rights, rather than a traitor to his country. Colonel Edward Marcus Despard, I am proud to meet you as a cousin!

Enter Ross Poldark

‘Poldark’, for those who don’t know, is a televised series of historical and romantic Cornish novels by Winston Graham, featuring scenes of handsome Ross Poldark galloping across the clifftops, and getting into various scrapes, often with the beautiful red-haired Demelza by his side. I probably wouldn’t have watched it so diligently, except that it already featured something else from real life that I was interested in. Scenes set in the ancestral home of the Poldarks, allegedly in Cornwall, was actually filmed at Chavenage House. This charming manor house near Tetbury in Wiltshire was where Robert and I had our wedding reception in 2009. It was also in use as a location just before and after our reception – guests wandering outside for a breath of fresh air bumped into actors Tom Conti and Susan Hampshire as they shot the final scenes for a film loosely based on a story by Rosamund Pilcher, for German TV. So I was thus glued to Poldark Series 5 on the screen one evening, with the aim of reliving our happy day, when I noticed that among the prominent characters was an Irishman named Despard. In the storyline, he becomes a battle comrade of Ross Poldark, and joins him, if I remember rightly, in an improbable escape from prison in France.

Below are some shots of our wedding at Chavenage House, Tetbury, the fictional seat of the Poldark family

I pricked up my ears: ‘Well, I have a line of Irish ancestors called Despard.’ My many-times great grandfather, the Huguenot Philip d’Espard also fled France, but in entirely different circumstances, during the first wave of religious persecutions against the Huguenots in the mid-16th century. He became a high-ranking engineer, appointed to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth 1st’s service in Ireland, acquiring money, land and status there. The family name shifted from d’Espard to Despard; his great-granddaugher, Alice Despard, married Richard Phillips (my maiden name) in 1697, and becoming my 7 x gt grandmother, did she but know it. I’d already heard about her from my father’s research, and was proud of having a few drops of French blood in my veins. But then Poldark was fiction, so it was a coincidence, surely? However, Despard is unusual as an Irish name, so maybe it was worth checking out.

And so I discovered that ‘Ned’ – Colonel Edward Marcus Despard – was indeed my second cousin, several generations ago. Although Poldark’s Ned Despard is almost nothing like the original in terms of character and background, the real and fictional storylines converge in the sad endings of Ned’s public execution. This was a public drama in itself, with many pleas for clemency from some of the highest figures in the land, who knew and understood Ned’s worth.

Representing Ned

I wanted to learn all that I could about this cousin and his life. And then to write about him – but this hasn’t been so easy. This blog has been brewing for a few years now. I made several attempts to get it going, but each time it stalled, until now, when I hope I have lift-off. Not because I lost interest, but because the more I looked into the subject, the more it seemed to grow hugely. How could I do justice myself to his story, in a brief and somewhat personal way? Actually, I don’t think I can. The historical aspects of his military campaigns, governorships, and finally his alleged association with revolutionary radicals, is indeed too complex and detailed to represent adequately here. I can only refer you to Mike Jay’s excellent study of Ned Despard, (see the cover at the start of the post) and to the various potted biographies that you’ll find on line – eg on Wikipedia . My role here is more to draw your attention to his story, and celebrate my discovery of him as a relative.

I will begin with the end.

At the Gallows

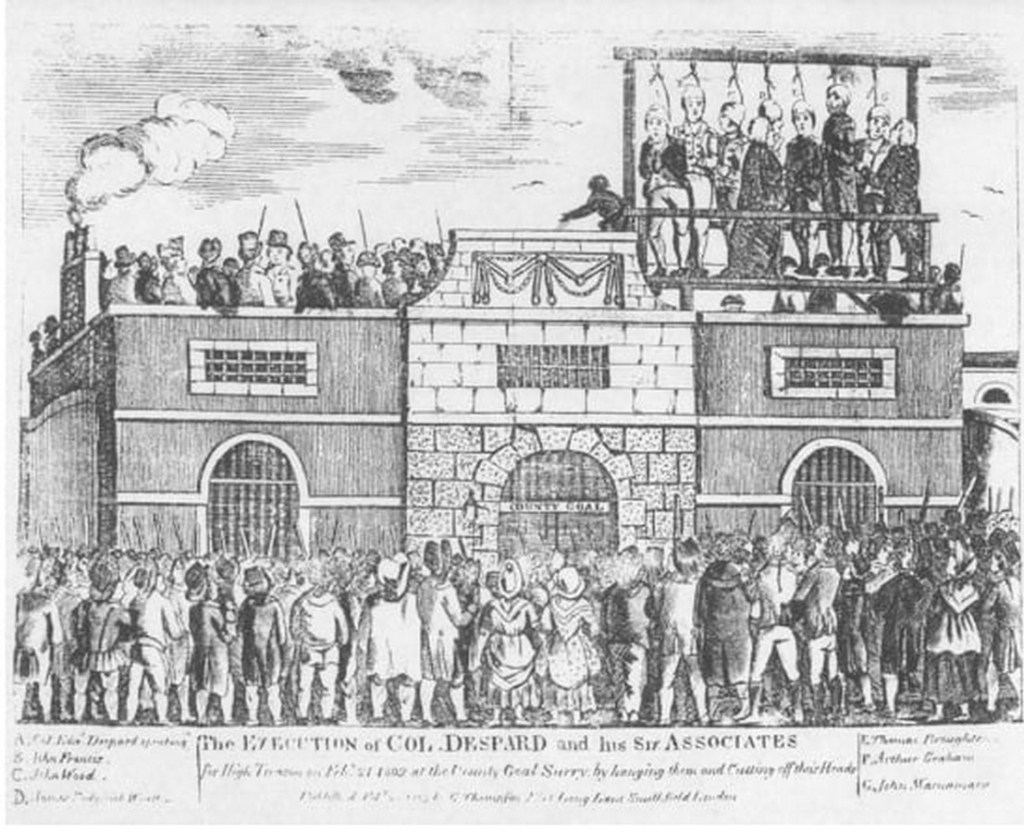

On Monday February 21st, 1803, Colonel Edward Marcus Despard was executed. A huge crowd of some twenty thousand people had gathered to watch him and his six fellow prisoners go to their deaths, on a public scaffold erected near Surrey County Jail, on what is now the south bank of the Thames. They were condemned as conspirators against King and country.

The event made its way into newspapers up and down the land, describing the public executions in minute detail, in the nature of a spectacle. But yet without this eagerness of early newspapers to report every element of a crime, court case or hanging, we wouldn’t have such a vivid picture sketched of these events. When it was Ned’s turn for the gallows, he asked permission to make a final speech to the crowd. This granted, he spoke passionately on the subject of justice and equality. (I’m including his words further on in this account.) Some of the newspapers sat in judgement – The Times called Ned’s speech ‘treason’ – and yet by today’s standards, it lays out the bedrock of a fair society. As Mike Jay points out, it is in fact in keeping with the modern United Nations declaration of human rights. (Jay, p.7)

After the speech, Ned stood on the scaffold platform with dignity, and addressed one of his fellow prisoners: ‘Tis very cold – I think we shall have some rain.’

But that ‘we’ no longer included him, for these were his last few words, and within a few minutes he was dead. He had already politely refused the counsel of priests, saying that he had quite made up his mind about God. and that his own religion already resided in his breast. He was then executed, by hanging and decapitation, on a charge of treason.

The evidence against him was flimsy at best, and false at worst. He received some small mercy in that the original sentence of being ‘hanged, drawn and quartered’ – the last man in British legal history ever to receive this full sentence – was repealed at short notice to remove the barbaric ‘drawing and quartering’. Even though he had loyal friends in high places, such as his old comrade-in-arms Horatio Nelson, they couldn’t commute his sentence further.

What had he done?

Colonel Edward Marcus Despard was condemned as a dangerous revolutionary, the charge against him being that he was planning to kill the King and overthrow the government. But there was no real evidence for this, certainly in terms of regicide or plotting a revolution. This was a man who’d been loyal to the British Crown through thick and thin. But since returning to London, he’d kept company with a few radicals, and was certainly interested in ideals of equality and reform. And in those days of paranoia about possible Revolution, that proved enough to hang him

He was singled out for infamy at a time when Britain was gripped by paranoia about a possible revolution. The government feared that the Revolution in France in 1789-99 might be replicated on British soil. Suspicion was rife, informers were everywhere. The earlier youthful idealism over revolution, such as was embraced by the Romantic poets Shelley, Byron, Coleridge and Wordsworth, was no longer acceptable. (see Romanticism and the French Revolution)

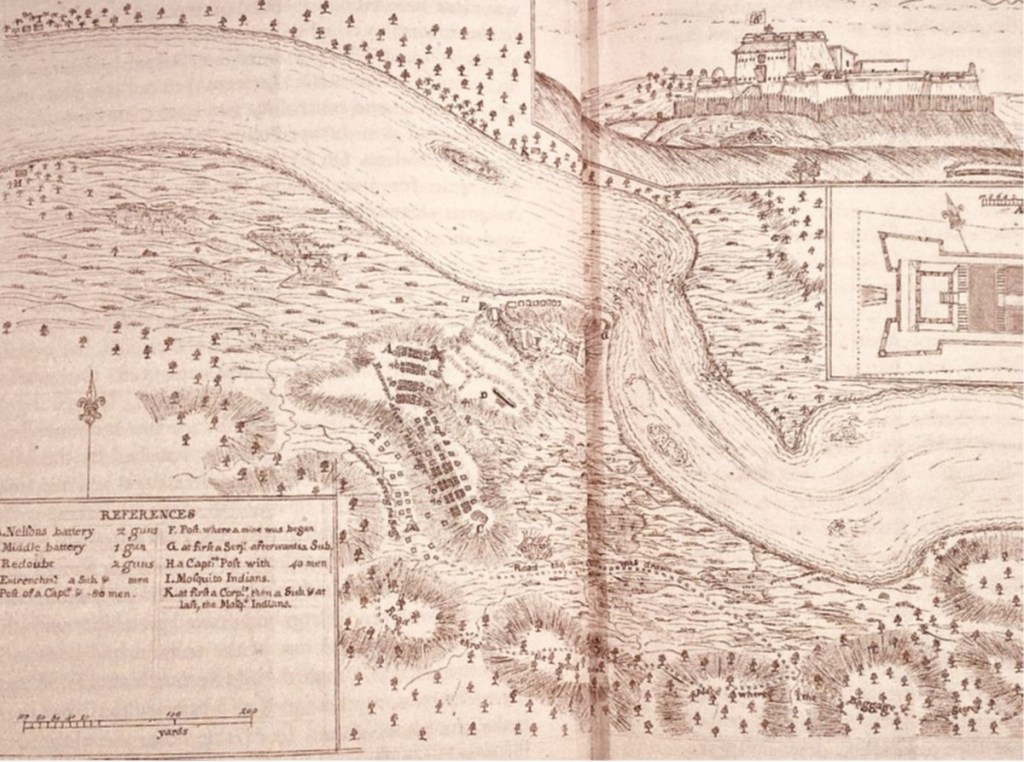

Yet Despard had served the British Government faithfully, at first as an army engineer and expedition leader, fighting bravely as a comrade alongside Nelson in campaigns in the Caribbean and Central America, where they managed to recapture Fort Immaculada from the Spanish. Both men suffered disease and hardship in the process – it was certainly no easy ride out there for officers either. Ned’s talent as a draftsman had been quickly recognised, and he was empowered to plan the routes for the military campaign. The image below, now in the British Library, is thought to be one of his original drawings, of the ill-fated Fort Immaculada. The British troops seized it back from the Spanish, but triumph was short-lived, as they suffered in the humid, disease-ridden climate, exacerbated by the damp walls of the fortress in which they were incarcerated once they had conquered it. (Jay p. 55)

Below, the remains of the fort today

After serving in military campaigns, Ned Despard proved himself as a responsible and conscientious governor in the British-ruled Honduras. That was no easy ride either, dealing with the conflicting interests of the volatile mixed population there. He stuck it out bravely, and only came back to England when he was completely out of funds, trying to reclaim the expenses owed to him, which he had subsidised out of his own pocket, including providing hurricane relief to the population.

After the headline news of his execution, Ned Despard almost disappeared from the public eye, until recent times – and even now his name and fate are little known, although some historians today do now consider that his death was one of the most important events of the age. ‘The day of Colonel Edward Marcus Despard’s execution is one of the most dramatic, and strangely forgotten, in British history.’ (Mike Jay) Perhaps this was because he was an anomaly, a one-off, who didn’t fit conveniently into the category of either public enemy or conventional British hero. And as we’ve seen in Britain recently with the Post Office scandal, where hundreds of sub postmasters were wrongly convicted of theft, injustice can go strangely unnoticed until the right exposure of it catches the public interest. In the case of the Post Office, the dramatized version on television suddenly woke the country up to what had been a huge miscarriage of justice. It’s too late now for Captain Ned to get justice, but at least we can get to know his story better.

Catherine, the wife

One of the other remarkable things about Ned Despard was that he married a black woman from Jamaica. This was a rare and bold thing to do at the time, especially when he returned to England with her. Although race was not openly discriminated against in Britain at the time, genuine mixed marriages as opposed to concubinage were certainly not the norm at the turn of the 19th century. Ned’s marriage was fuel for his critics to throw on the fire. One of the reports against him sneered that when Ned was seized from home in London to be taken to court, he had been ‘found in bed with a black woman’ – no mention of her being his lawful wife.

Even some of the Despard family and their descendants spoke of her being a housekeeper, rather than acknowledging her true position. Jane Despard, a niece of Colonel Ned’s, wrote loftily in her memoirs in 1828: ‘Whether the unfortunate man was ever married to his black housekeeper or not according to his own notions I do not know, but Uncle Andrew, the only one of the brothers who kept up much intercourse with him…seems to think he was not. She was one of the train of black servants he brought over with him.’ She mentions that after the execution, although Catherine was granted a pension, ‘of course none of his relations would acknowledge her’ and she went to Ireland, ‘and there she died’. Actually, what happened to Catherine later on is uncertain, but it is clear that without her husband to vouch for her, the ‘black housekeeper’ was relegated to a position way outside of the family circle. She did apparently have some genuine friends and allies among her husband’s supporters, so there’s hope that she was able to live privately in reasonable peace and comfort.

Catherine was in fact an educated woman; her mother had been a ‘free woman’, so neither she nor her daughter was a slave. Catherine was capable of mixing in upper circles of society and showing the social manners required. She petitioned for her husband tirelessly during the years he was kept in a debtor’s prison pending the final trial. One of her letters survives in the National Archives, a plea that he should be kept in better conditions. This is my transcript of her writing, as far as I can decipher it:

Dear,

I take the liberty of requiring to know of you if there any order from His Grace the Duke of Portland, for the usual allowance of state prisoners to be given to Colonel Despard, who is confined in the House of Correction, in Cold Bath Fields, five weeks next Sunday, without the common necessaries of life. When he was first taken to that prison, he had one of the upper apartments given him, which he found very airy, but since his commitment he has been removed to the ground floor, with not so much as a chair to sit on or a table to take his vitals of[f]; where he finds the mornings and the evenings very cold, and not so much as a fire to warm himself; and where he is deprived of books, pen, ink, and not even allowed to see me but for a few minutes, and that among felons and people of the worst of crimes. In consequence of I wrote to His Grace the Duke of Portland this day is a week (?) to request His Grace will be pleased to direct (some) change to be made in respect to his treatment, but as I did not mention my address, I presume is the (cause) of my not receiving an answer. I entreat Sir that you will be so obliging as to let me know whether anything is dun [done] or will soon be dun [done] to alleviate his distress (?) for in short he is treated more like a vagabond than a gentleman or a (?) prisoner.

I am Sir your most obedient (?)

Catherine Despard

Friday Morning

Upper Berkeley Street

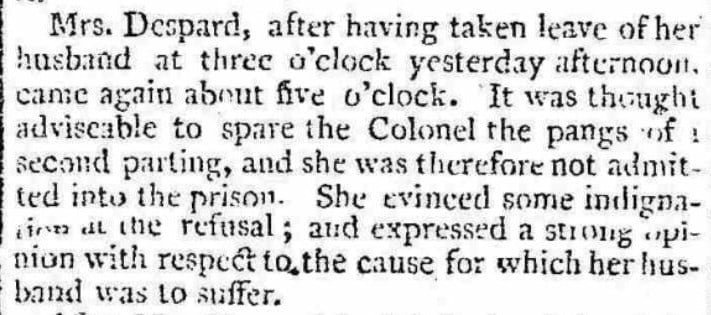

Right up until the bitter end, she fought to stay with him, as the newspapers reported when she asked for one last chance to see him in prison:

Ned and the Huguenot line

The first member of Ned Despard’s line arrived in Ireland from France during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, fleeing the persecution of Huguenots after the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. (See Refugee Ancestors: A Huguenot Famiily in Devon). Philippe d’Espard, as he was named, must have moved in esteemed circles in France, since he was swiftly appointed as ‘Engineer, Royal commissioner for Queen Elizabeth I for confiscated church lands’. (The question of Irish-English relations is of course a vexed one, which I won’t go into here.) This aptitude for engineering, seems to have passed down through the family, as his grandson William Despard (1635-1717) became Col. of Engineers for King William III. Edward Marcus Despard, our subject here, born in 1751, was Philippe’s 3x great grandson, and he too was singled out for his skill as an engineer and draughtsman when he joined the army. The family generations also made money from mining iron ore

In the various studies of Ned Despard that I’ve read, it’s assumed that by the time he was born, the Despard family had merged seamlessly with Anglo-Irish gentry. In one sense, that’s almost certainly true, bearing in mind how my 7x grandmother Alice Despard, (Ned’s great aunt), was assimilated into the Phillips families of Kilkenny and Tipperary. Alice Despard became betrothed to Richard Phillips in 1697, and the contract (discovered by my father during his research) was drawn up ‘between Richard Phillips of ffoyle [Foyle] in the County of Kilkenny Gent of the one part and William Despard of Cranagh in the Queens County Gent’ . Alice’s father William was to pay Richard £230, and Richard would settle his estate upon their children.

However, even if Alice became a proxy ‘Phillips’, I suspect that it may have been different for those who carried on the Despard name. Overall, little attention has been paid by biographers so far to Ned Despard’s Huguenot roots. But those origins were not so far in the past, just six generations back. I was told tales about my 3x maternal grandfather by my own grandfather, who recounted how Edward Owen was a foot soldier in Wellington’s army, fighting Napoleon. (He got the details significantly wrong, but there was enough info for me to trace Edward’s career in the 84th Regiment of Foot, as it turns out!) And in regard to the Huguenots, surely the further persecution of them in France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, just 65 years before Ned was born, would have still reverberated through the Huguenot communities already in exile? An account of Huguenot refugees in Ireland can be found here, though note that this particular Despard line almost certainly fled to England first, before Philippe d’Espard took up residence in Ireland.

Left to right: Edward Marcus Despard, (a portrait possibly painted by George Romney), centre: my great uncle Samuel Phillips b. 1849: right, my father Charles Ormonde Phillips b. 1913 on his graduation from Cambridge. Do you see a likeness? I certainly do!

Ned stands up for justice

I think that it’s likely a readiness to fight injustice was already running through Ned’s veins. His family had stood up for religious freedom, and were among the Huguenots who were exiled, executed or massacred for their beliefs. Their values of tolerance and inclusiveness might still have been deeply felt by the Despard family in Ireland, by some family members at least. And until his ‘disgrace’, Ned Despard was appreciated by his family, even if claiming the credit for his good characteristics: ‘In his manners he was like the rest of his family, a perfect gentleman,’ his niece Jane Despard claimed. Others too remarked on his mild manner and desire for fairness. Jane nevertheless tuts over his pride and ‘lack of religious principles’; in his youth, ‘this unhappy man, Edward Marcus, used to detest alike his grandmother, bible and coffee, and to avoid both when he could.’

Jane relies on family hearsay, as she herself never met this uncle, and it sounds as though he was practically airbrushed from family history after his execution: ‘His fate is known to you so I need not enlarge on it. People talk of him now according to their political bias, but we may leave him to his heavenly Judge.’ Despite Jane’s shortcomings as a biographer, and her distance from her uncle in time and proximity, it is nevertheless wonderful to have some first hand family recollections about him. (In an earlier post, ‘A Tale of Two Samplers’, I wrote about how I set out to trace the little girls who stitched two 19c samplers which I have in my possession. I mentioned how, after slogging through official records, it was a joy to come across a personal recollection of one of these girls as a middle-aged woman, married to a miller, and giving local children free rides in her horse and cart.)

A desire for justice and equality

During his time as First Commissioner and Governor in what are now the Honduras, Ned Despard focused on fairness for all the peoples of his colony, irrespective of their status or colour. He had some very awkward folk around to deal with – the Baymen guarding their plantations, the Shoremen with semi-legal trade. There were Maroons, who were runaway slaves, plus Irish convicts and people of assorted ethnicities, including the indigenous peoples of the area, all with their different desires and objectives. Colonel Despard’s insistence that there should be equality between people of different colour and race did not go down well with everyone in the colonies. Ironically, when challenged about this, he said that as British law did not disciminate between races, neither would he in its territories. So were these Huguenot values coming to the fore, carried through the generations, despite his family’s well-established position in the gentry of Ireland? And did these values later inform Ned’s gallows speech when he said that he had ‘been a friend to truth, to liberty, and to … the poor, and the oppressed.’? I leave you with a newspaper report of his final address:

Morning Post Feb 22

Colonel Despard was brought up the last [of the prisoners], dressed in boots, a dark brown great coat, his hair unpowdered. As each appeared on the platform a buzz prevailed throughout the mob, and particularly when the soldiers’ red jackets were seen. Early in the morning Colonel Despard desired to speak with the Sheriff and Sir Richard Ford, to whom he communicated his wish to address the spectators. — They told him they had not the least objection to his carrying that wish into effect.

The Colonel ascended the scaffold with great firmness. His countenance underwent not the slightest change, while the awful ceremony of fastening the rope round his neck, and placing the cap on his head, was performing. He looked at the multitude assembled with perfect calmness. The Clergyman who ascended the scaffold after the prisoners were tied up, spoke to him a few words as he passed. — The Colonel bowed, and thanked him.

The ceremony of fastening the prisoners being finished, the Colonel advanced to the edge of the scaffold, as nearly as the rope by which he was tied up would allow, and made the following speech to the multitude:

” Fellow Citizens, I come here as you see, after having served my country, faithfully, honourably, and usefully served it, for thirty years and up wards, to suffer death upon a scaffold for a crime of which I protest l am not guilty. I solemnly declare that I am no more guilty of it than any of you who may be now hearing me. But, though His Majesty’s Ministers know as well as I do, that I am not guilty, yet they avail themselves of a legal pretext to destroy a man, because he has been a friend to truth, to liberty, and to justice.” (There was a considerable huzza from part of the populace the nearest to him, but who, from the height of the building from the ground, could not, we are sure, distinctly hear what was said.) The Colonel proceeded: — ” Because I have been a friend to the poor, and the oppressed. But, Citizens, I hope and trust, notwithstanding, my fate, and the fate of those, who no doubt will soon follow me, that the principle of freedom, of humanity, and of justice, will finally triumph over falsehood, tyranny, and delusion, and every principle hostile to the interests of the human race. And now having said this, I have little more to add.” (The Colonel’s voice seemed to falter a little here. He paused a moment as if he had meant to say something more, but had forgotten it. He then concluded in the following manner — ” I have little more to add, except to wish you all health, happiness, and freedom, which I have endeavoured, as far as was in my power, to procure for you and for mankind in general.”

For those who wish to read all the details of the execution as published in the press of the day, I’m adding in a PDF version of my transcript of one version (all versions that I’ve come across are in fact very similar). Be warned, it makes for grim reading.

A footnote on the family history:

After my Poldark discovery, I was now keen to claim ‘Ned’ Despard as my ancestor. I set about clarifying the family tree, and reading whatever I could find about his extraordinary life. My father’s line mainly comprises the Phillips family of Tipperary and Kilkenny, but with the entry of Alice Despard, my 7x great grandmother, the link between the two families was forged. It seems that the branches of both families lived fairly close to each other, and that the interaction probably continued. Alice, for instance, went to live with another Phillips relative after her husband died.

My father had put his heart and soul into researching his Phillips genealogy, but stopped short of investigating the Despard line beyond Alice Despard herself. So what he hadn’t followed through became a line of discovery for me! Family historians of an earlier generation, like my father, were often keener to follow through the patrilineal family name (Phillips in this case) rather than branch off into what was sometimes called the ‘distaff’, ie female, lines. This is partly because of our current and predominant patrilineal naming system, where the father‘s name is passed down rather than the mother’s. I think too, that in pre-internet days it made the research much more do-able, following the family name itself through the records.

Could my connection to the Despards be trusted though? DNA can easily reveal nowadays that we are not who we think we are, and there were many coverups of genuine parentage in years gone by. But John Despard, who runs the Despard Genealogy group on Facebook, analysed my DNA test with my consent and confirmed that my family line does indeed join the Despard line in its expected branch in Ireland.

Ned’s fate and future

Ned Despard was first a national hero, then a national traitor in his day – even though thousands still championed him, he was found guilty of plotting to kill the King and plunge the country into anarchy. And although largely forgotten since then, he has turned up again in the unlikeliest of places, in a Cornish romantic adventure series on television. I’m glad that he is portrayed there as a man of honour – perhaps he has another round of fame coming.

And finally –

For those who might want to compare the on-screen Ned Despard with the historical man, here are the differences between the fictional Despard and the real-life one

Behind the scenes

- Ned doesn’t appear in the novels by Winston Graham.

- Edward Despard was a real historical figure.[4]

- Events in Despard’s life were not portrayed by the BBC production of Poldark in a chronological way:

- He was recalled to England by the Crown in 1790, not 1800. He was investigated for two years, and later imprisoned in 1792 to 1794. He was imprisoned again twice: in 1798, and then again in 1802 to 1803. In the TV show, he was just imprisoned in 1800 and 1801.

- He was imprisoned for the third time and executed because he was named by the government in a conspiracy to kill King George III in 1802.

- He was executed on 22 February 1803. In the TV show, he was executed in 1801 instead.

- He and Catherine had their child before 1790. In the TV show, she doesn’t have a child until 1801.

- Events in Despard’s life were not portrayed by the BBC production of Poldark in a chronological way:

Of further interest

The Unfortunate Colonel Despard – Mike Jay (Bantam Books 2004, 2019)

Memoirs of Edward Marcus Despard – James Bannantine

The Despards in Ireland 1752-1838 – Jane Despard

Red Round Globe Hot Burning – Peter Linebaugh

The British Newspaper Archive – for accounts of the trial and execution

https://www.facebook.com/groups/despard

Refugee Ancestors: A Huguenot Family in Devon – a previous blog in Cherry’s Cache, charting the escape of another Huguenot family in my ancestry, the Mauzy family, who fled from La Rochelle to Barnstaple

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to Mike Jay, for his email correspondence, and the references and information which he supplied

And to John Despard, of the Despard Genealogy Facebook page