What kind of terrain did George Ivanovich Gurdjieff grow up in? What landscape shaped his boyhood? Recently, in August 2025, I had a rare opportunity to see for myself, on a study tour to Eastern Turkey. I’ve long been enthusiastic about Turkey, going there first as a student to teach English, then drawn back again and again to the magic of Istanbul, and the fascination of the Lycian coast, Cappadocia, and the Sufi traditions both of Konya and hidden in the heart of Istanbul. I even co-owned a house in Kas for a few years! But I’d never visited its Eastern edges – the names of Lake Van and Mount Ararat carried a magical aura, and the chance to see more of the ancient Silk Road, and Byzantine remains was too good to miss. It was a new opportunity, since only in recent years has the area been safe for visitors, following the reconciliation between the government and Kurdish forces. So, following the old adage, ‘If not now, then when?’ I signed up.

But it was only after I’d made the booking that I realised that this was Gurdjieff territory too. I had read Meetings with Remarkable Men several times, but not remembered the place names, or connected it with the tour. We were going to visit Kars, where he spent much of his youth, the deserted city of Ani where he hid out for a while, and Van to where he travelled with his father for a traditional singing contest. The trip now had a whole added layer of significance. It was an extraordinary journey, into remote terrain and with spectacular archaeological sites, and very friendly people. It was hot, it required stamina, and the food wasn’t as good as Turkish food can be, but it was a wonderful experience.

Gathering together my thoughts, impressions and pictures after the tour, I decided to share these with others who might also be interested in the Gurdjieff connection. I can certainly say that it’s added a new dimension to my knowledge about his life and teachings.

As I want to move straight into describing the landscape, I’ve put a brief note about Gurdjieff and his work at the end of this post, for anyone unfamiliar with him, plus a note about my own connections.

KARS -Gurdjieff’s Family Home

The city of Kars was originally part of Armenia, but became a Russian province between 1878 and 1917. Although it’s now within Turkey, like most of the surrounding area, its culture used to be basically Armenian. It was where Gurdjieff and his family moved to from Alexandropol, some sixty miles away, after his father’s fortunes as a cattle owner failed. Gurdjieff’s chronology is never precise – it’s generally considered that he was born in 1866, though no means certain – but it seems that he spent much of his boyhood in Kars.

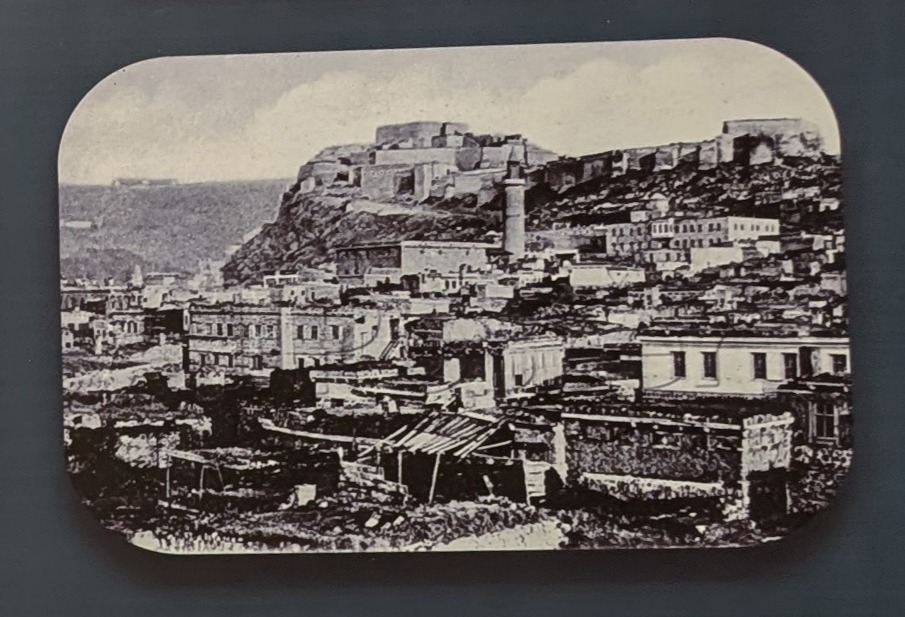

The Kars of today is of course very different from that time in the late 19th century, but the fast flowing River Kars still runs around the city, and the deserted citadel still crowns the view. It’s famous for its cheese, and there are many herds of cows grazing in the surrounding countryside, plus flocks of geese which are also a local speciality on the menu. Many of the substantial old Russian buildings are still standing and in use; sometimes the black stone (local basalt) gives them a gloomy feel. Others are painted in pastel colours of green and yellow, in the Russian style.

And dotted in around the town are smaller dwellings, some very similar to Russian country homes.

Kars seems to be in a much better state than it was! In 1877, when British Intelligence Officer Frederick Burnaby arrived in the city he said: ‘The streets of Kars were in a filthy state. The whole sewerage of the population had been thrown in front of the buildings.’ Gurdjieff himself described Kars as ‘quite remote’ and ‘extremely boring’, and even the guidebook to Eastern Turkey published in 2014 reported that ‘the mud never seems to disappear’. However, in 2025, after a long hot summer, our group found it a pleasant, quiet, friendly and mud-free town. The residents seemingly know how to enjoy summer, since they can often suffer five months of snow in winter. (Orhan Pamuk’s novel ‘Snow’ focuses on this feature.)

Somewhere here in the town, in a fairly humble dwelling after losing his fortune, Gurdjieff’s father worked as a carpenter, and in Kars itself the young George became a chorister at the Russian Military Cathedral. I asked our guide to take us there; he showed us what is now the Fethiye Mosque. The original Orthodox Cathedral was topped with onion domes and had a parade ground outside; later the domes were stripped off, and it was turned into a sports hall before being brought into use as a mosque. It was moving to step into this space and imagine – sitting on a rather garish blue carpet designed for Islamic prayers – that Gurdjieff had been here again and again for rehearsals and performances. As a choral singer myself of many years standing, I know how much time and commitment this takes.

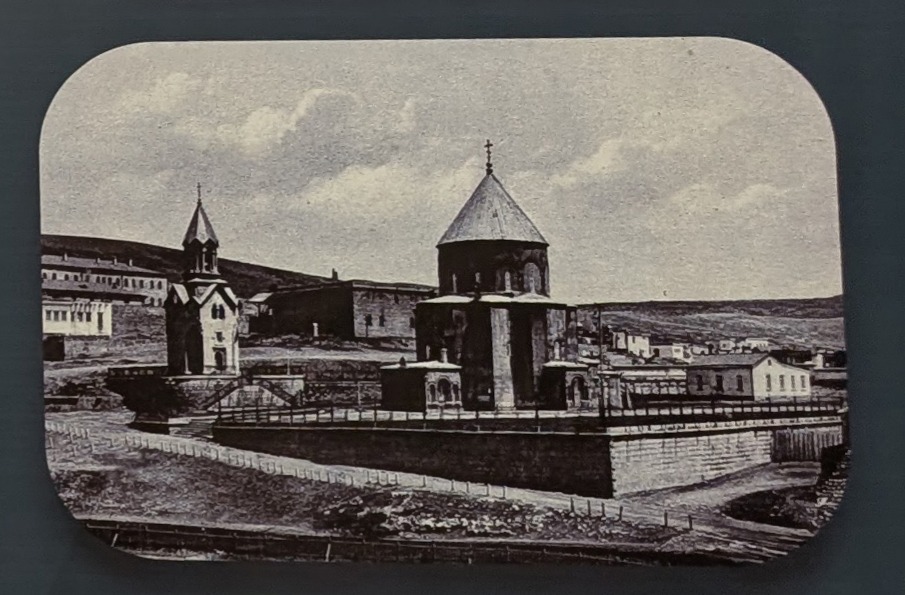

In internet listings for the city, especially those relating to Gurdjieff, there seems to be some confusion between the Russian Cathedral and the Armenian one. This military Cathedral, with its domes and long rectangular shape, in front of an old parade ground, I am reasonably sure is where Gurdjieff sang, and where his tutor Dean Borsh presided. The other contender, the Armenian Twelve Apostles Church is an ancient building dating from the 10th century, sitting near the base of the citadel hill. It’s now a mosque, but with a warm welcome to all visitors. Here, I felt an ancient spiritual presence, something special that reminded me of the chant ‘Lord have mercy,’ which Gurdjieff employed in one of his dance movements and in a wider context. Did he perhaps come here as a boy, and sense this himself?

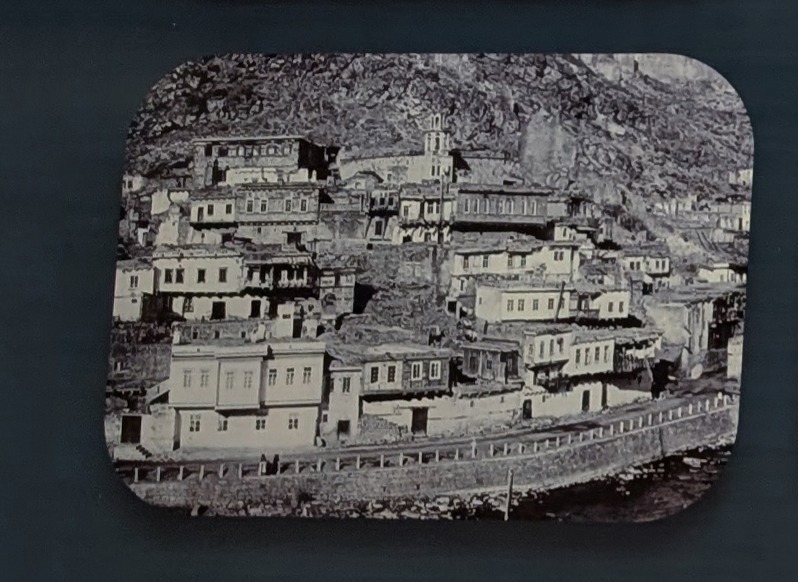

I’ll finish this section on Kars with some old photos from the Museum, showing how the city was in Gurdjieff’s time. Please excuse the quality of these pictures, which not only photos of photos, but I’ve also had to separate and enlarge them from a composite display – the quality is as good as I can get it!

The Ancient City of Ani

Ani is the most magical of places – a former Silk Road city of ancient Armenia, built around the 10c and deserted in the 14th century after raids and earthquakes decimated it. Today it is just on the Turkish side of the re-drawn national boundary. It’s now carefully conserved and treated as an open air museum. Three hours wasn’t enough to do justice to it.

Below: the city walls, ancient churches, and the remains of a Zoroastrian fire temple, with its four pillars.

One or two of the churches, ruined or semi-restored, are used as mosques now in accordance with the policy of the Turkish government. The view through the window looks across the river valley straight into Armenia – my phone was convinced I was already in Armenia! It would have all been Russian occupation of Armenian territory in Gurdjieff’s day.

Here are the caves which link up with the underground passages which form the substructure of the city, and which played a pivotal part in Gurdjieff’s account of Ani. He and his friend Pogossian were searching for ‘a quiet place where we could give ourselves up entirely to study. Arriving in Alexandropol, we chose as such a place the isolated ruins of the ancient Armenian capital, Ani, which is thirty miles from Alexandropol, and having built a hut among the ruins we settled there, getting our food from the neighbouring villages and from shepherds. ’ (Meetings with Remarkable Men p.87 -Picador 1963)

They lived simply, reading and studying, and doing a little digging around ‘in the hope of finding something, as there are many underground passages in the ruins of Ani.’ They discovered a blocked up monastic cell, and a pile of parchments, some of which could still be read – if only they could understand the kind of ancient Armenian they were written in! They returned immediately to Alexandropol with the parchment so as to get to grips with the translation. When they finally succeeded, they discovered a source of lost knowledge, and a mention of the Sarmoung Brotherhood…’This school was said to have possessed great knowledge, containing the key to many secret mysteries.’ And there the tempting trail begins…the existence of the Sarmoung Brotherhood has been sought, disputed and revered ever since.

Whether or not this tale is faithful to the facts, Ani certainly makes metaphorical sense in Gurdjieff’s search for ancient universal wisdom. As the Unesco website declares: ‘Ani was a meeting place for Armenian, Georgian and diverse Islamic cultural traditions that were reflected in the architectural design, material and decorative details of the monuments.’ And ‘secret tunnels’ long out of use are indeed a verified feature of Ani. ‘The remoteness of the uninhabited city of Ani, with its impressively standing monumental buildings, over an invisible landscape of underground tunnels and caves surrounded by deep river valleys, provides a mostly unaltered window onto the past.’ https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1518/ I recommend a browse of this website in which even such an official and rigorously factual description of Ani conveys the city’s unique magic and importance as a crossroads of culture. Did G. I. Gurdjieff and Pogossian really discover lost manuscripts? Well, they could have done…that at least is for sure!

We enter a mythic realm with this transition in the book, and whether it rests on literal truth or a kind of metaphorical reality, is up to the reader to decide. The Second Series, Gurdjieff declared, which was the book in question, is intended ‘To acquaint the reader with the material required for a new creation and to prove the soundness and good quality of it.’ We ourselves have to enter that creative dimension, and he gives us a good send-off for our own explorations.

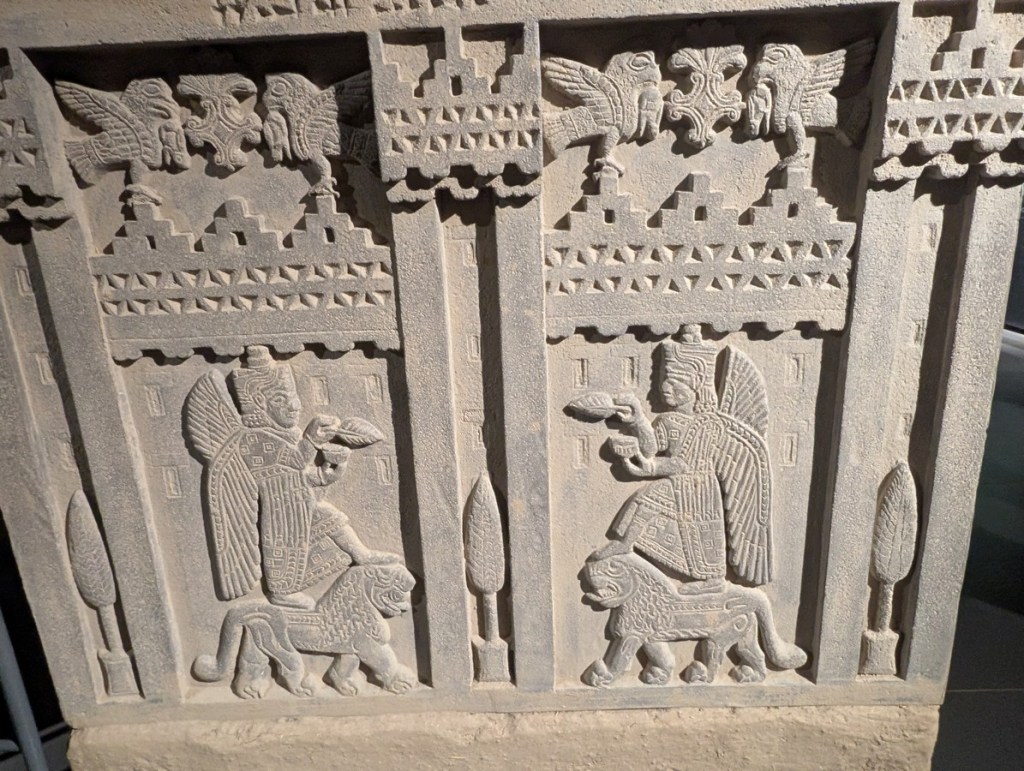

The area is full of mysteries, ancient carvings and strange mythical creatures…

The Landscape

Turkey had endured an extra long and hot summer when I visited, so most of the landscapes I saw were golden brown, apart from swathes of green around water sources. There was a haunting beauty about the empty hills which roll on into to the distance, and awe at the craggy mountains which tower up here and there. Occasionally there were strange geological phenomena, such as the scatterings of obsidian on the road between Erzerum and Kars, and later petrified streams of black magma, rolling many miles away from their source at Mount Ararat. Mount Ararat itself is not too far away, and we glimpsed it like a hazy, snow-capped apparition a couple of days later, in the vicinity of Dogubeyazit.

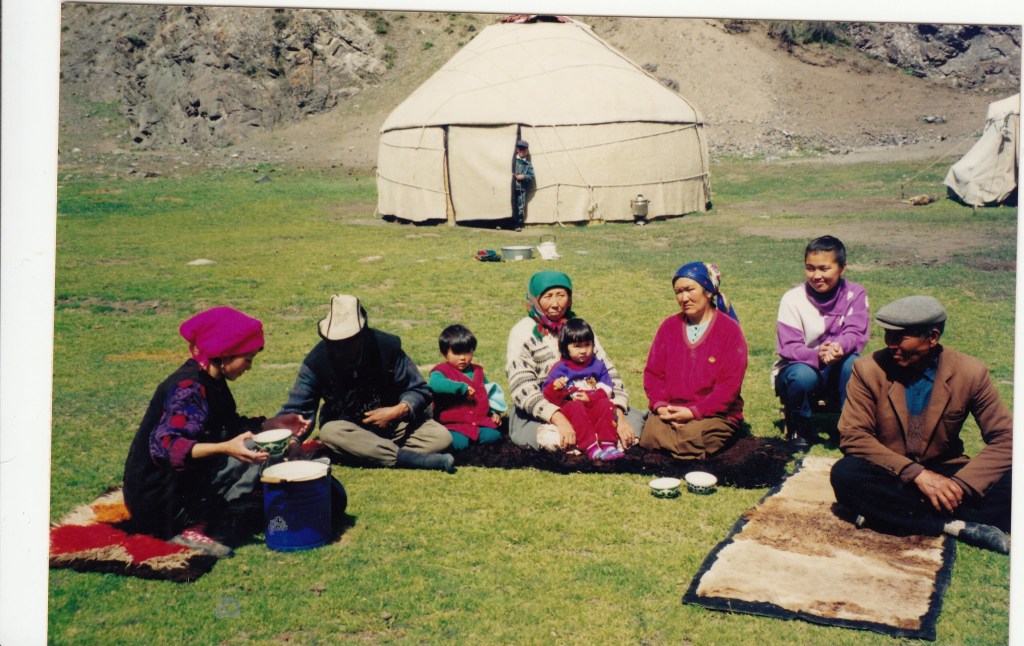

Shepherds and flocks

In the foreground, near the roads, we saw open unfenced land which provides free range grazing for sheep, goats and cattle. Many of these flocks and herds were attended by a single shepherd or cowherd.

The shepherds played a quiet, but significant role in this terrain. And Gurdjieff noticed this, and probably conversed with them on his travels. He once said that a shepherd in the hills could learn far more about meditation in three days than the a modern seeker would in three years! (I’m paraphrasing, until such time as I rediscover the quote.) As we traversed the seemingly boundless landscape we saw such solitary shepherds or cowherds with their animals and they were, as far as I could see ruminating, sitting, or walking slowly – and not glued to a phone. So the conditions are still there for people to have this kind of solitude, which becomes an immersion in the spirit of the landscape, leading to a sense of presence beyond the chatter of everyday life.

The Ashokhs

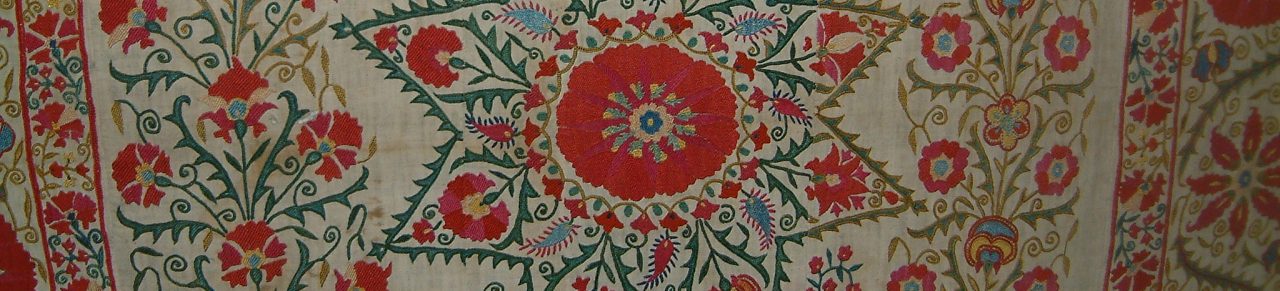

I had trouble identifying whether the ashokhs – such as Gurdjieff’s father, the bards who were singers and reciters of epic tales – were still known in Eastern Turkey. Our Turkish guide didn’t recognise the word. Eventually I found it listed as ‘Ashugh’ (Armenian) or ‘Ashik’ (Persian). Most of Gurdjieff’s territory from his boyhood was Armenian, even when occupied by Russians.

And I did find traces of the tradition. One evening, in Kars, we booked a special restaurant dinner and performance, with what turned out to be amazing leaping dances, and ‘a contest’ between two singers, playing traditional instruments (ud or saz). Was this a remnant of the old ashokh contests, which Gurdjieff and his father attended? It could well be. I asked the guide, who explained that yes, they were – in my words – slagging each other off, and vying to out-sing each other, with good humoured insults and bravado. The songs seemed to be love songs without any hint of the epics which Gurdjieff described, but this was probably only one example of today’s performances. I’ve since learnt that there’s a cultural centre in Kars, where ‘Ashik’ performances happen every day, to keep the tradition alive.

Gurdjieff tells us that he and his father travelled to Van for an ashokh contest, so I was curious to see the city, which is where we spent the last three nights of our tour. Van itself is still a very lively place, where people of different cultures meet. In Gurdjieff’s time it was an Armenian province, although Armenians themselves were in the minority. Today the majority of the population are Kurdish, who are outgoing and friendly to visitors. There were very few of us on the streets who’d come from Europe; the majority of today’s visitors pour over the border from Iran, eager for night life and (comparative) freedom!

Below: Varied views of Van, including my hot but triumphant climb to the top of the fortress!

The vast lake is known as the ‘Sea of Van’ as you cannot see the other side of it on the horizon. It’s ‘silky’ to some swimmers, ‘oily’ to others , and only one kind of fish can live in its alkaline waters, a kind of mullet which we sampled for lunch one day. (Rather like bland sardines.) There were however a few flamingos around the lake, and I saw a small group of bee eater birds, with their exotically iridescent plumage. I was also super keen to meet a Van Swimming Cat, a white, long-haired breed, who often have different coloured eyes (eg one blue, one green) and a penchant for water. We did see a few in a cat shelter, where they are trying to save and conserve the breed. Gurdjieff, fond of animals, might very well have encountered one of these. I was wondering why they are white, until I remembered the five months of snow in the region! Good camouflage.

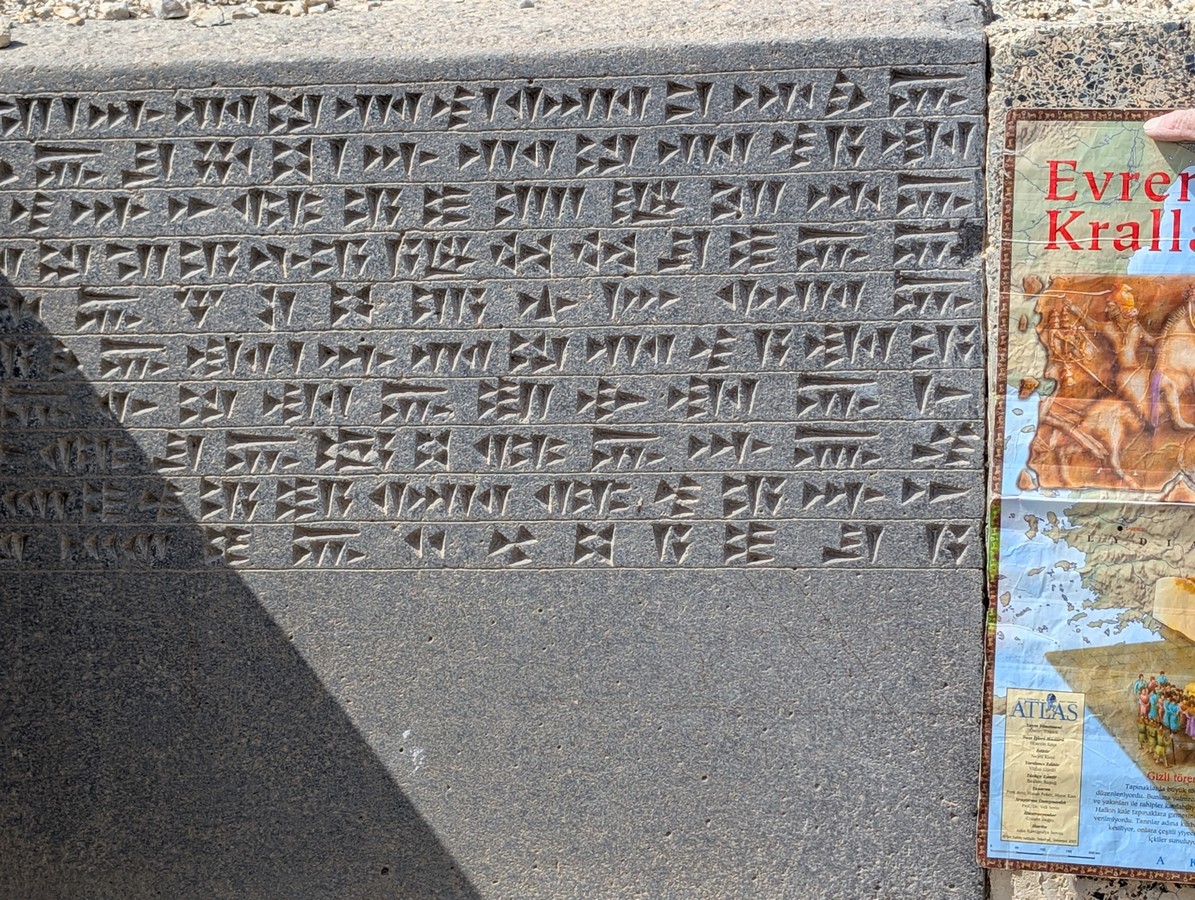

The Urartians

Van in ancient times was called Tushpa, and was the capital of the Urartian kingdom, which existed between about 900-600 BC. This fascinating culture was richly endowed with a multitude of deities, of whom the chief was Haldi, the sun god; they possessed a cuneiform language, found engraved into stone, and were both neighbours and enemies of the Assyrians. Their citadels were often built on mountaintops and we visited one such, at Cavustepe. It was wonderful experience standing on top of the mountain ridge, surveying the valleys below and the hills and mountains beyond. A sense of being proud, and free. Here, an 85 year old guide showed us around; he had worked at the site with the archaeologists for 70 years, and deciphered the cuneiform script, on which he is now the world’s leading authority. Mehmet Kushman is coming to the end of his active life, and we were privileged to walk through the high reaches of Cavustepe with his knowledge and guidance. I asked him in a quieter moment, if he ever felt the presence of the Urartians around him there. He paused for a moment, then with dignified emotion and a half laugh, declared, ‘I am Urartian!’ I believe him.

Would Gurdjieff have visited some of these mountain fortresses? Most probably he would have climbed up the one at Van, as we did – a real trek in the heat! Did he know about their culture? Perhaps not, but it’s certainly in keeping with the sense he engenders for us of ancient peoples, hidden sources of knowledge, and lost kingdoms.

My trip has left me with a yearning to keep something of the spirit of this place in my soul. And perhaps to follow it up with a trip to Georgia and Armenia. Seeing places which have inspired writers and teachers of wisdom can be both moving, and profoundly instructive in a non-verbal way. I have a better sense now of where this particular line began.

Who was Gurdjieff?

For anyone who hasn’t encountered Gurdjieff, here’s a brief resume: George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was a Greek-Armenian philosopher, traveller and teacher, who lived from around 1866-1949. He came from a Christian Orthodox family, but sought out teachers and sages who could instruct him in ancient wisdom, which he then absorbed, researched and formulated in his own way. Perhaps it’s fair to say that the core of his message is to ‘wake up’ from the sheep-like state we live in much of the time, in order to realise our full being, and allow the self to ‘remember’ its true nature. Although not mainstream, his teaching has had a great impact on 20th century systems for personal spiritual growth. He brought the ‘enneagram’ into public view, now extensively used in psychotherapeutic contacts. His methods are usually taught as ‘The Gurdjieff Work’.

My own connection: While my own path has been chiefly in the tradition of Western Tree of Life Kabbalah, I have also been a member of groups studying Gurdjieff’s writing and his dance ‘movements’. I’ve also read and re-read his books over the last fifty years, plus practically all the memoirs written about him. I am not a fully-fledged Gurdjieffian, but I admire and respect his teachings.

‘Meetings with Remarkable Men’

The places featured here are those mentioned in Meetings with Remarkable Men. Here, in the ‘Second Series’ which follows Beelzebub’s Tales, Gurdjieff describes his early life and some anecdotes from his boyhood, followed by a search for truth and ancient teachings as a grown man, in remote areas of Central Asia and beyond. Was this memoir a genuine account of his life and wanderings? My own view is that many of these ‘later ‘meetings’ from his adult years are most likely to be fictionalised, semi-mythic accounts of what may have been real events. They convey their own truth, but not in literal form, But I know of no reason to doubt that most of his descriptions of his childhood and adolescence are genuine memoir. His visit to Ani – again in my own opinion – is one most probably based on his personal knowledge of the ruined city, which was within easy reach of his two home cities, Kars and Alexandrapol. What he found there is a matter for speculation!