‘A Long Long While’

I first heard this story delivered with great relish in a folk club in Birmingham, back in the 1960s. The story-teller was Alan Bishop, a bearded native of Blackheath in the Black Country. It wasn’t the last time I heard it either, as it was one of Alan’s favourites, and he would end it with a gleeful grin, while he waited for the punch line to sink in. Alan was in fact so fond of this story that his family made sure it was recited it at his memorial service in 2017.

It’s bin a long, long while since fust this tale was told

You’ll laugh your eyes out when you hear it, as Eynuck did of old

Two men went sanking down the street

When soon two fighting dogs they hied

They stuck ‘em in an empty butt, lid on

To fight it quietly out inside

Now yow con fight to your heart’s content

And both stood nigh to listen

Bist gonna have a bet? said one

Now tell me, bist or bissen?

They placed their bets the while

And the clamour in the butt was chronic

What thrills they got from that there fight

It was better than a doctor’s tonic

But soon alas, dead silence reigned

And each mon looked at t’other

They raised the lid – an empty butt

Them dogs – they’d etten one another!

I think the title would be better as ‘Them two dogs had etten one another’ – but then that would give the game away. But isn’t there more to this story than just making you laugh? True, it’s yet another comic tale in the traditional Black Country fashion, with a preposterous ‘double take’ conclusion, but I think there’s something of the metaphysical in it too. After all, when cosmologists and theologians struggle with the question, ‘How did Something come out of Nothing?’, then surely, a convincing answer to the even more difficult question of ‘How does Something return to Nothing’, deserves serious consideration. Yes, ‘them two dogs had etten one another’, and that settles it.

And this is just one of a multitude of Black Country jokes and stories. Why is it such a ‘funny’ place? Why do people still tell jokes the whole time, especially, it seems, in pubs? When writer and actor George Fouracres, returned to his native Black Country to research an article on Black Country humour , the first person he asked was his father. “Everyone round here thinks they’m a comedian,” reflected his father. Black Country folk, he reckoned, will always find a way to “av a loff abaat” whatever situation they find themselves in.

Enoch and Eli

These are the mythical duo who drive the juggernaut of Black Country jokes. They are very often the narrators of the stories, tripping each other up in dialogue, scoring points and laughing at the ways of the world. In the tale above, only ‘Eynuck’ (Enoch) appears, but his pal Eli is always just around the corner. The pair, often referred to in Black Country dialect as Aynuck and Ayli, have become the stock characters , often of stories where one of them makes the other the butt of the joke. Aynuck and Ayli have weaseled their way into cartoons and comedy clubs, and have even had a reading room named after them. More on their origins later.

Black Country humour

Black Country and Brummie humour is dry, sharp and mostly delivered dead pan. The inhabitants love to send themselves up, as well as everyone else. Given that ‘meat’ and ‘mate’ are pronounced the same, along with ‘bison’ and ‘basin’, and ‘whale’ and ‘while’, there’s a fund of jokes to be had about these potential misunderstandings.

Aynuk: What’s the difference between a buffalo and a bison?

Ayli: I doh know, I’ve never washed me hands in a buffalo.

Aynuk and Ayli were fishing in the canal:

‘Me mate’s fell in the canal !’

‘Owd it appen?’

‘I just took a bite ov me sanwich an me mate fell out.’

Ayli, Aynuk and their mate Noddy Holder go into a clothes shop and Noddy says to one of the assistants, ‘I’m re-forming Slade, I want to buy some new stage clothes. I need a pair of flared trousers, a wide collar shirt, platform boots and a mirrored top hat.’

‘Kipper Tie?’ asks the assistant.

‘Oh thanks,’ says Ayli and Aynuk ‘Two sugars and milk please.‘

Leaving the puns hastily behind – there’s plenty more in that vein- it’s worth digging deeper into the nature of Black Country wit. The jokes are often about people being daft or stupid, at least on the face of it. But there’s usually a wry twist, a double take, a lightning quick reversal of expectations which kickstarts a guffaw. This kind of wit tickles your brain. It’s a type of humour in the tradition of the Wise Fool, similar to the Turkish and Middle Eastern stories about their folk hero, known as ‘Nasr Eddin’ or ‘The Hodja’. It appears to be ridiculous but is often rather clever.

Aynuk: People always say as Black Country folk is thick, doh ‘em?

Ayli: They do, mate.

Aynuk: Well I read in the paper as ‘ow the population of London is the densest in the whole country.

Yes, right! Insult them, and they’ll find a crafty way of turning it back on you. Indeed, the Black Country has long celebrated its own wit. T. H. Gough’s cheap-and-cheerful collections of Black Country Stories were a popular seller and ran to five volumes in the 1930s. I have one on my shelf now.

I’ve been around Brummie and Black Country humour since I was about ten – although I’m not completely a native, I spent my formative years in the Birmingham area. I am told I still break into a Brummie accent when excited. Strictly speaking, Birmingham and the Black Country are not exactly the same thing, but for many of those years, we lived on the edge of the Black Country itself, near Aldridge and Walsall. The two areas – Black Country and Birmingham – have much in common, but as Birmingham was industrialised earlier, its local customs and language were diluted to a greater extent, as it grew into a city and had a influx of workers. The Black Country – an area covering the boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton – is said to have retained its distinctive outlook and language for much longer. However, the name ‘ Black Country’ has been in use for a while, at least as early as the 1840s, referring to the seams of coal prevalent in the area, or the soot which began to cover everything .

Black Country dialect is a rich heritage which is valuable to the English language as a whole, as it’s apparently the closest one we have to Middle English. It’s Germanic speech – note the ‘bis and ‘bissen’ in the dog story at the start, similar to German ‘Du bist’, meaning ‘you are’.

When I gave a talk once at the British Council in Florence, Italy, I was put up for the night by the director of and his wife. They were a highly educated, well-spoken couple who you might assume had come from the Home Counties. But no, they were proud natives of the Black Country, and completely bilingual. They loved to speak ‘Black Country’ together, impossible for an outsider to understand and very useful, they told me, when they didn’t want their children to understand what they were saying! Sadly, I also learnt from them that schools had in their day tried to drum Black Country speech out of the children, and the ‘nippers’ ended up with one language for the classroom, and another for the playground.

Black Country words describing what children (nippers, babbies) might be doing

Riling is fidgeting or rolling about

Slummocking is standing or walking in a slouching, slovenly way

Chobbling is chomping or munching loudly, especially on your rocks (hard sweets).

Blarting is crying or sobbing.

Clarting about is messing around.

Wagging it means playing truant

Language coach

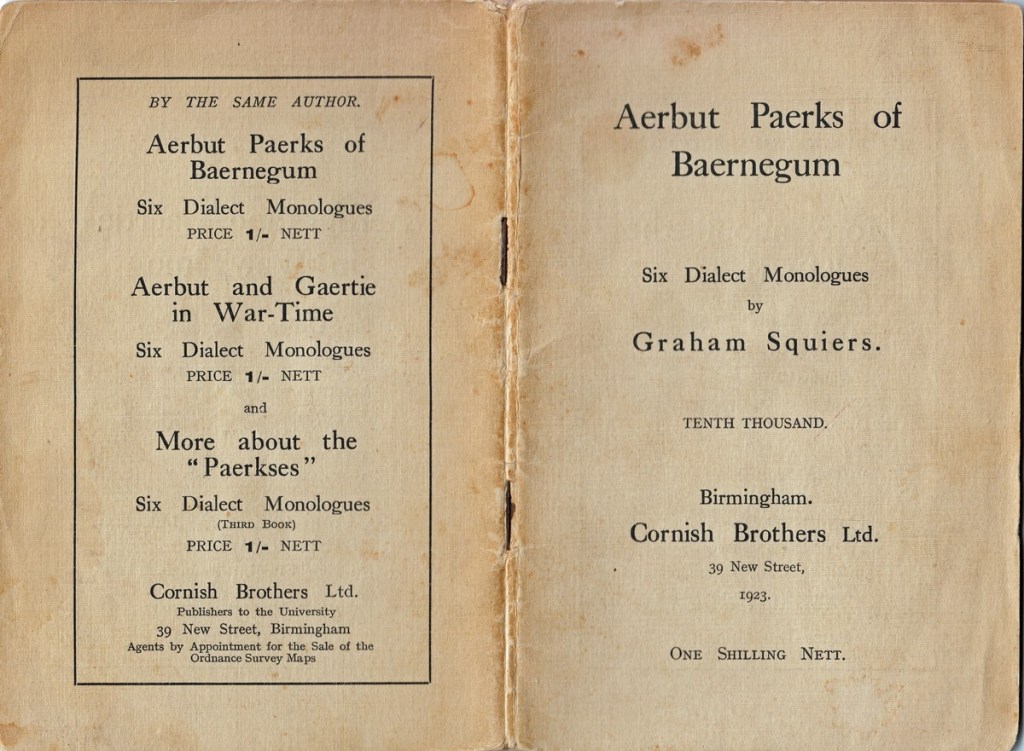

If you’re concerned that you might not be able to master the accent, then there are guides to help you. I have in my possession Aerbut Paerks of Baernegum: Six Dialect Monologues by Graham Squiers, published in 1923. Fork out one shilling, and you could be speaking like a native – even if it wouldn’t perhaps be considered quite culturally appropriate today. But in the grand old days of the monologue (think Stanley Holloway and ‘Albert and the Lion’) it would indeed ‘be a loff’.

Here’s Aerbut (Herbert) getting married:

‘Ah kid. I’m sorry as yo couldn’t get orf from ther waerks and cum to ther weddin’. We daint ‘arf ‘ave a tim I tell yer. I took Gaertie t’ave ther banns put up faerst. Ther bloke wanted ter know ther date of me baerth, and wot I waerked at and ‘oo my old mon wos, and ‘edaint ‘arf get shearty when I told ‘im I’d got a strorberry mark under me left ear’ole. Then he arksed Gaertie if ‘er wos a spinster. ‘Er says, “Gar off, I’m a baernisher of caertin ‘ooks.”’

But the double act of Herbert and Gertie Parksis trumped by that of Aynuk and Ayli, the favourites in all the stories and jokes, the duo with the innate shrewdness of the Black Country folk. How did these names come to be chosen? After all, Eli was a High Priest of Shiloh in the Bible, and Enoch an ancestor of Noah who ‘walked with God and was not’. Not much to laugh about there, surely? Such resonant and robust Biblical names were popular in the 19th century, though, especially in non-conformist families. Black Country expert Jon Raven confirms that ‘Methodism had a particularly strong foothold in the Black Country amongst all strata of society.’ (Although he goes on to explain that the Methodists and the similarly numerous Wesleyans were often at each other’s throats!) According to one source, the pairing of the two names Enoch and Eli originated in the late 19th century music hall, as used by comedian Ernie Garner. (Little Book of the Black Country – Michael Pearson, History Press 2013). Somehow, they passed into local culture and became a permanent fixture. Aynuk and Ayli was the name of a much-loved comedy duo (John Plant and Alan Smith), well-known in the Midlands from 1984 to 2006.

Joke Themes

The pub has remained a prime source of material for jokes, as well as a venue where people are still eager to listen to them:

Aynuck and Ayli in the pub.

Ayli: Doh drink no more, mate, yo’ve ‘ad enough.

Aynuk: ‘Ow do yer mek that out, I ay drunk.

Ayli: You must be, yer face is gerrin’ blurred already.

The Dog

Dogs are popular in other A & A jokes too:

After seeing the sign in the big store, ‘Dogs must be carried up the escalator,’ Aynuk spent three hours trying to find a dog.

Aynuk went round to see Ayli’s new dog which kept barking and leaping up at him as he walked up the path.

‘My word ‘e doh ‘erf bark some,’ said Aynuk,

‘Yes’, said Ayli, ‘but you know the saying ‘a barking dog never bites?’

‘Ar,’ said Aynuk, ‘I know the saying and yo know the saying but does you’r dog know it?’

The ‘Ooman

The wife and mother-in-law as tyrant, nuisance and millstone was often the butt of old Black Country jokes – maybe this has changed a little now, with the advent of sharp-witted Black Country female comedians such as Josie Lawrence and Meera Syal? So I shall ignore those sorts of joke, except for this one, which I reckon helps to level up the playing field.

A little lad went home feeling really excited that he’d been chosen for the school play. He told his father, ‘I’ve got the role of an old married man’ His father patted him on the head sympathetically. ‘Never mind son,’ he said, ‘maybe next year you’ll get a speaking part.’

Daft Jokes

And then there are the plain daft ones, which nevertheless make you giggle:

Aynuk: How do yo stop moles diggin’ in the garden?

Ayli: Hide all the shovels.

Aynuk: How many hundredths are there in an inch?

Ayli: Cor, there must be thousands, mate.

Grandiose ideas

Black Country folk like to dream big:

Aynock thought Ayli was in need of a little further education so decided he would take him to the big city, Birmingham.

Aynock led him round the city explaining what building was what, and the local history attached to them. Eventually they arrived at Victoria Square, and by this time Ayli’s brain was in a right spin. Suddenly, Ayli turned and saw the large building and said to Aynock, ‘Is thet a palace our kid?’

‘Naa’, says Aynock, ‘that’s the Council House.’

‘Bloody hell,’ says Ayli, ‘I’ve got me name down for one of them.’

More Black Country words

I’ll finish off with a few more delightful dialect words and expressions:

Scrage means to scratch, scrape or graze the skin.

Fittle is food, and ‘bostin’ fittle’ is ‘great food’

Yampy means daft, or someone who’s losing the plot.

Never in a rain of pigs pudding means something will never happen.

Clarting about is messing around.

Noggy means old-fashioned or outdated.

Fizzog is a face (from the word physiognomy); tell someone to stop sulking with, ‘Put yer fizzog straight.’

Oil tot means feeling satisfied and happy, from the days when working men would have a tot of olive oil before drinking beer, in the belief that it would stop them getting very drunk.

Go to the foot of our stairs! is a local exclamation of shock or surprise.

This ain’t gettin the babby a frock and pinny means ‘We’re wasting time’.

So, for now, Keep out th’ossroad! (Mind how you go!)

Ta-ra-a bit! (See you!)

Contribute to the post – If you’ve any Black Country jokes or words that you’d like to share (keep them clean, please!) just submit them via the Comments/Leave a Reply box. They’ll appear on site as soon as I’ve had a chance to ‘approve’ them.

Update! My good friend and former Archers’ scriptwriter Mary Cutler has contributed a few, from her lifelong association with Birmingham and the Black Country:

‘It’s looking very black over Bill’s mother’s ’ – It’s likely to rain soon.’

‘Outdoor’ – Off-licence

‘Yam yams’ – affectionate (local) appellation for people with a strong Black Country accent

‘Go and wash your ickle donnies’ – to a child

References

Black Country words in this piece are contained in an article in the Birmingham Mail

Tales from Aynuck’s Black Country, Jon Raven, Broadside 1978.

Acknowledgements

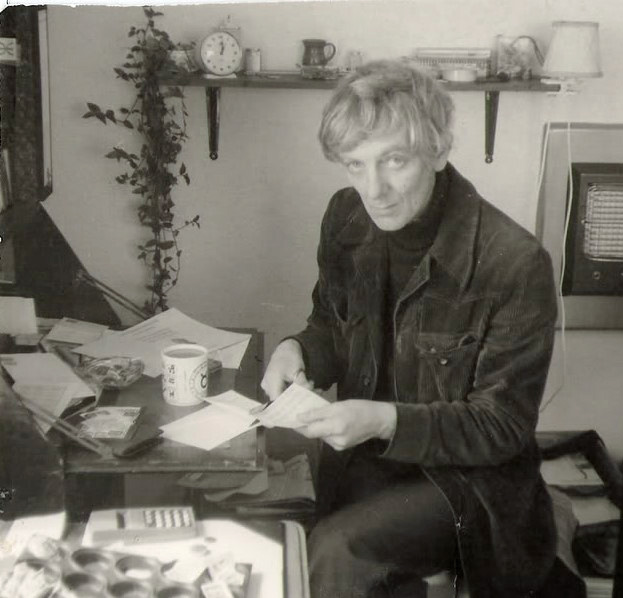

Many thanks to my old folk singing buddy, Pam Bishop, who supplied photos and a copy of ‘It’s been a long, long while’. View her website here.

Thanks to renowned singer Peggy Seeger, who helped me with general queries about folk music in the 1960s. This is a link to the description of the Radio Ballads (see below) on her website.

And to another folk buddy, collector Doc Rowe, who re-discovered the photo below and sent it to me. Find Doc’s website here.

How I became interested – My interest in folk song, stories and language grew strong through my connection with BBC Radio producer Charles Parker, who with Ewan McColl was responsible for the iconic Radio Ballads. In Birmingham, in the mid 1960s, I was a member of the regular folk workshop run by Charles, along with Pam and Alan Bishop, (who are featured at the start of this post) I dedicated my book Your Life, Your Story: Writing your life story for family and friends, to Charles Parker.