For the month of October, I have prepared two posts on the deep past of our inheritance. Autumn here in the Northern Hemisphere now leads us towards the darkest time of year; many cultures celebrate festivals of the dead after harvest time, when darkness begins to prevail. Halloween and the Day of the Dead are probably the best known of these customs.

So in the months of declining light, our thoughts may track back more often to distant memories. And we might find time in those darker evenings to research the deeper areas of life, including our origins in terms of family history.

My own father was dying over Halloween, but he actually made it into the small hours of All Saints’ Day (Nov 1st). I was glad of this, as it is a day of more peace and less turbulence. At about 5am, I got the call to say he had passed away. But when I rushed out of my house in Bristol to drive up to Shropshire (too late to bid him farewell) I couldn’t leave straight away. I discovered that the chaotic energies of Halloween had been at work in the night, and my car windscreen was now smashed. However, perhaps none of us can pass on to peace without a breaking up of the familiar world around us. It seemed symbolic.

Listen to the spine-tingling ‘Soul Cake’ song sung here by the Watersons folk group. People would go door to door around the time of Halloween and All Souls’Day, begging for a soul cake.

The Circle and the Line

I have taken a different approach in each post. My first post here is about the ‘circular’ form of viewing our ancestry, which can open up a new perspective on our direct ancestors, through grandparents, great grandparents and so on.

The second will look at some of the more mysterious and magical aspects of ancestry, and explores the idea that it may still in some sense be present for us today, and that we can have a relationship with this. This is about the resonance of our ancestral line and how it may play a part in our lives.

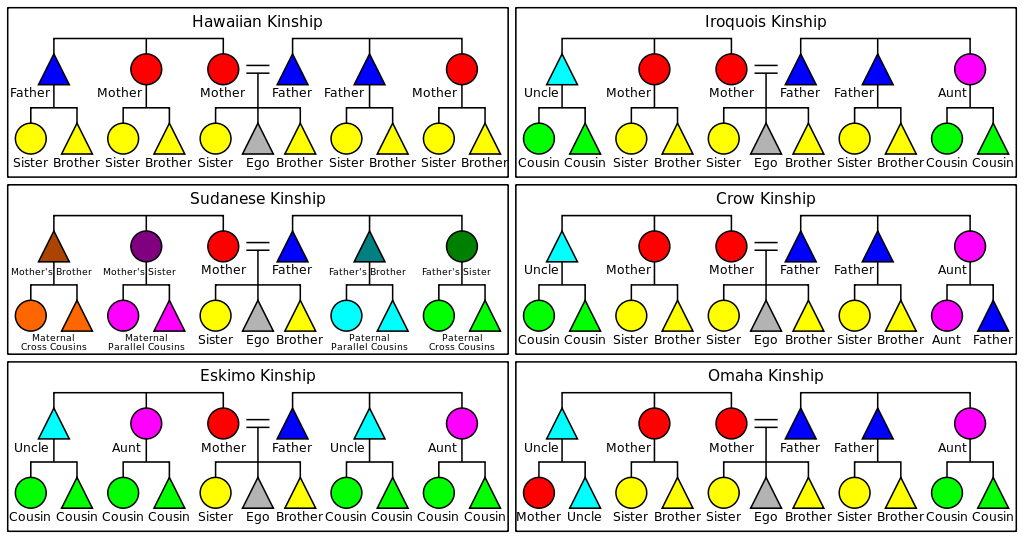

The Circle of the Ancestors

As part of my degree at Cambridge, I studied anthropology. But although I loved the course, I was alarmed to be told that understanding ‘kinship systems’ was one of the most important elements of the syllabus. Really? I had hoped to learn about myths and rituals, songs and customs, maybe even a bit of magic or witchcraft… And it turned out to be rather heavy reading, untangling the complexities of who can be considered a brother, aunt, cousin, or potential marriage partner in each particular tribe. But anthropology certainly did open my eyes to other ways of viewing different systems of human relationships. I learnt that all in all, there is no one fixed pattern of how to define a family or a relative.

All this can have a bearing on family history. By the time I came to research mine, in the early 2000s, I had forgotten the nuances of Nuer kinship degrees, but I did know for sure that there was more than one way to cut up the ancestral cake. This had largely been ignored by an older generation of genealogists in our Western Societies, who used to focus almost exclusively on the paternal line, which usually carries the family name. The ‘distaff side’, as the mother’s line was disparagingly termed, was often neglected. Why bother with it, was the general genealogical view, when the all-important family name could not be traced up and down the generations? (And heaven help us if there is a hint of illegitimacy! Better cover it up if possible.) However, in a curious way this practice actually benefited me, because my father’s diligent research on his paternal Irish ‘Phillips’ line – including any distantly-related aristocracy that he could dig up –largely ignored my mother’s family history. It was thus new ground for me to investigate.

Like many other people, I didn’t care much about family history until both my parents had died, and suddenly I was next in the firing line. Perhaps this is commonly a time when we claim our family inheritance, in its intangible sense, along with any material goods left to us. It may turn into a job of stewardship, done according to our own beliefs, as it’s the oldest generation who tend to be the gatekeepers to the family stories, keen to impart the ones they choose, hiding the ones they don’t like.

We can and do change the lens through which we view our ancestors. Knowing this also offers opportunities to ‘choose’ our ancestors, in the sense of selecting that viewpoint. It can be argued that DNA is the sensible way to determine our family connections, but that doesn’t necessarily give us the full picture, since beyond a certain degree of blood kinship, DNA may not share common traits. And for many of us, the ‘story’ of the family is more important anyway, including members who’ve been adopted, born out of wedlock, etc. One branch of my Phillips family is linked to me by the story of two boys, cousins of a sort, who were taken into the main family home at Gaile in Tipperary, while their father purportedly went off to fight for the British in the American War of Independence. And yet, no one can quite be sure whether they were blood relatives – the DNA doesn’t confirm this – or illegitimate and more distant descendants, or even no relation at all, just welcomed into the family and taking its name. In the long run, does it matter? They are firmly embedded in its story now.

So I’m giving over this blog to one particular way of not only seeing, but experiencing the ancestors. It’s ‘the circle’ method, which I’ll now describe here in a slightly adapted compilation from my book ‘Growing your Family Tree: Tracing your Roots and Discovering Who You Are’.

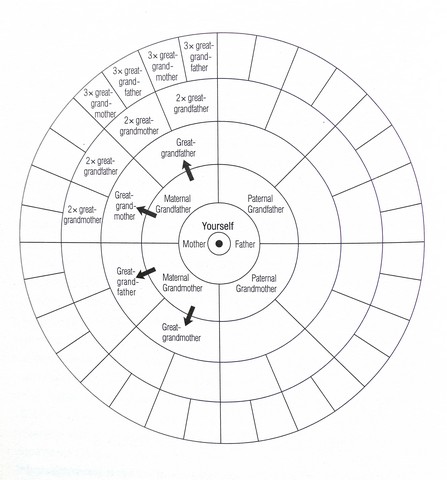

Setting up your Circle of Ancestors

I first heard about this way of invoking your ancestors at a concert celebrating the life of John Clare, a poet who was himself firmly attached to his roots and ancestral landscape. One of the musicians performing there mentioned a family history project which his daughter had brought home from school. She had been asked to enter all her direct-line ancestors into a series of concentric circles, expanding from a central point representing the person in question to include each generation further back. In this case, therefore, the musician’s daughter, would be named at the central point, and her mother and father placed opposite each other on the first circle that surrounded her. The second circle would be marked with the names of her four grandparents, and so on through six circles in total, ending with a final circle containing sixty-four ancestors, all of whom would be her 4x great-grandparents.

It fired my imagination, and back at home, I tried to draw neat circles divided in the correct way, divisions doubling in each circle. It was tricky! Eventually, I achieved a rough template and started to fill it in. This was at a time when I hadn’t got so far with my family history, and inevitably I ground to a halt in different areas of the circle. There weren’t many 3x great-grandparents that I could name at this stage, and very few 4x ones. But the concept, of standing in the centre of circles of ancestors was compelling. I still come back to it frequently, and sometimes check to see if all those sixty-four are now included. (Not quite!)

Creating the Circle: Exercise

See if you can create something similar, but I suggest a reduced version to make it more manageable, which will probably end at the circle of thirty-two. I find that thirty-two direct ancestors are plenty, if I want to know them as individuals, and discover their stories. Thirty-two are as many as I could hold in my mind at once, and as this diagram works as a visual aid and a tool for connecting with your ancestors, I recommend keeping it within practical bounds. Bear in mind that if you were to go some nineteen generations back, you would have over half a million ancestors in your circle!

Contemplating the Circles

Now you can start to make use of your chart. What does it feel like, to be at the centre of your ancestral circles? Try the following:

- Look at the finished chart (even if not all the names are complete); gaze at it for a few minutes.

- Then close your eyes and try to visualise it. Call up the names of those you know; this is probably easiest in terms of one circle at a time, your grandparents followed by great-grandparents and so on.

- Can you see in your mind’s eye a circle of sixteen, then thirty-two grandparent ancestors, even if you cannot differentiate each one of them? Which ones do stand out clearly? Which are shadowy figures? Which faces do you know, from your own life or photos, and which are as yet unknown?

- Acknowledge them all with gratitude and respect for the life they have passed on to you.

This is a powerful exercise, which can produce different types of effects. You may experience the ancestors as protecting and caring. But being surrounded by family in this way might also come across as suffocating and restricting. There is no ‘right’ way to experience it, and it may well be that you will find that it varies at different times. After all, this is on a par with family life – sometimes it’s the best support we can have, and sometimes it curbs and frustrates us. But if you keep this as an exercise to return to, you may find that your sense of being connected with your ancestors grows, and that in some sense, they become more ‘alive’ to you. Use the circle as a personal ritual to greet and get to know them.

As Awo Fa’lokun Fatunmbi says, writing in connection with the Yoruba people of Africa:

‘Communication with your own ancestors is a birthright….You cannot know who you are if you cannot call the names of your ancestors going back seven generations. Remembering names is more than reciting a genealogy, it is preserving the history of a family lineage and the memory of those good deeds that allowed to the family to survive.’

Related blogs:

Seduction, Sin and Sidmouth: An Ancestors’ Scandal

The Ancestors of Easter Island

A Coventry Quest: Finding a Grandfathe