A couple of months ago, I mentioned that we were leaving Devon for Gloucestershire. Well, now the move has taken place. It’s just a week since we uprooted from Topsham, and are now in the process of settling into Minchinhampton. However, I can’t leave completely without waving a fond farewell to the county we’ve enjoyed exploring so much in the last nine years. It was actually my second time of living in Devon, but the first time in the 1980s was based more on the edges of Somerset and Exmoor. So this latest sojourn has allowed us to spend more time by the sea, and exploring East and South Devon. My files are full of photos saved from numerous visits, days out, walks and coffees-on-the-beach. (Not to mention crab sandwiches.) I’ve had to choose selectively, and with pictures that I hope you’ll enjoy. I haven’t tackled Dartmoor, which is a world in its own right, but I hope to do so in a future blog. As for Topsham, where we’ve been living, I’ve covered this extensively in at least seven posts focusing on the town, and Exeter also gets a good mention in a few of them. So here goes with fourteen of our other favourite Devon destinations. And just to make things easier – for me, rather than for you – I’ll display them in alphabetical order.

Budleigh Salterton

Our favourite destination for a Sunday morning coffee. Big choice to be made – from the Lime Kiln car park, shall we stroll to the end of the bay, and watch the swirling River Otter gush out into the sea? Or along towards the town, where you can sit on a bench under the red stone cliff and hear the sea eachoed back behind you.

We’ve rented a beach hut there twice, and when the Devon flag is flying by the boats, you can buy fresh fish. The pebbles are famous, being part of an ancient river that flowed across when France and England were joined – the estimated age of these beautiful stones is around 445 million years old.

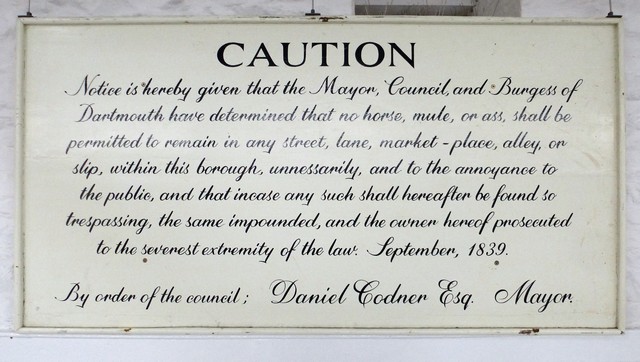

Dartmouth

A joy to visit, but much further away, so we have usually gone there out of season, when the traffic is lighter. Crossing on the old chain car ferry from Kingswear is an added treat, and there are boat trips upriver to Greenway, Agatha Christie’s old home, and on to Totnes.

Dawlish Warren

A spit of shifting sand, eerily long, and a rewarding place for birders and walkers. At the inner end, by the road and even a train station, it’s a place for a holiday camp and seaside amusements. Beyond that stretches a mile and a half of dunes and wetland and, curiously enough, a golf course . It’s a struggle to prevent the whole area eroding, but it remains a nature reserve and groynes try to hold the sea and winds at bay. Some experts say it won’t exist for too much longer though. You can gaze across to Exmouth seafront from the Warren – or even catch a ferry from Exmouth to get you there.

East Budleigh

We never pass through East Budleigh without greeting ‘Sir Walter’, son of this village. If you stroll half a mile out along one of the lanes, you’ll arrive at Hayes Barton, the farm where he was born. The Raleigh family were settled in the area, and Walter’s father, also called Sir Walter, was involved in the tumult of the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549.

Exmouth

Now we’re at Exmouth itself. Bustling, thriving, with both river estuary and a long, long sandy beach to enjoy. It has a cosy little cinema, and an up-and-coming Festival, which I am proud to say is now managed by my daughter Jess Magill! I’m afraid you’ve missed it for this year, but if you want to browse in happy anticipation of next year, here’s the link. When Robert and I were not seeing family in Exmouth, we tended to wander at the far end of the 2 mile stretch of beach, and sometimes up onto the cliffs there. We shall miss Orcombe Point!

Exmouth was also where I met Boss the Eagle Owl for the second time. (At a festival, not flying wild!)

Killerton

Killerton is just a few miles from the sprawl of Exeter, but it feels as though you’re deep in the countryside. It’s the former home of the Acland family, and now National Trust, with beautiful stretches of gardens and wilder parts beyond to be explored. Everyone is fascinated by the bear house! That’s the small, thatched one…and yes, they really did keep a pet bear in there at one time. We have loved getting an early burst of spring with the magnolias and camellias coming into flower.

Knightshayes

Yes, it’s another National Trust house which just happens to be next in the alphabet to Killerton. From here the Heathcote-Amory family could once look down across the estate to their factory in the wool-weaving town of Tiverton. Again, it’s another wonderful place to come in spring. We’ve brought grandchildren and picnics, and they were thrilled by the Gothic interior of the house, just right for a murder mystery. In season the walled kitchen garden is a marvel, and we’ve bought heritage tomato plants there like ‘Chorni Krim’ (Black Crimea) which gave us wondrous black fruits in our greenhouse. All photos on this blog were taken by me, apart from the one of the kitchen garden, since I was never there quite at the right time with my camera.

Kitchen Garden, Knightshayes, Wikimedia Commons

Lympstone

We shall miss the washing lines of Lympstone – the village on the Exe Estuary which looks as if it’s on the coast of Cornwall.

Otterton

And we’ll miss the charming cottages of Otterton, where we nearly bought a house….and then Minchinhampton beckoned us back again…

Salcombe Regis

This is Salcombe Regis, not to be confused with the town of Salcombe which is the sailing mecca much further down the coast. Salcombe Regis lies just beyond Sidmouth – the village is at the top and the beach is a long, long way down. Our walk was memorable. First, because we met the celebrated Olympic dressage rider Mary King on her horse in the village, which is where she lives. Secondly, because we got stuck in something a bit worse than a bog, almost a slurry pit, when we were attempting the descent via a badly marked footpath through the fields. Eventually we made it down to the beach, and enjoyed dramatic skies as we walked back along it to Sidmouth. This part of the Jurassic coast is prone to cliff falls, so do take care if you venture along the beaches here.

Sidmouth

And here we are indeed, at Sidmouth, conveniently next in the alphabet. I’ve chosen not to go overboard on the quaint 18th century Gothic cottages or the splendid Regency seafront, but rather to feature some nostalgic images of taking Very Small Grandchildren there, a good few years ago now. And in passing, to note that for Robert and I, our adult trips to Sidmouth nearly always ended up with crab sandwiches at Duke’s Hotel on the promenade!

South Molton

South Molton isn’t exactly a tourist destination, though it is one of the gateways to Western Exmoor, via Molland Common. We stopped there on such a trip because it has very ancient connotations for me. In 1980, my former husband and I made a brave (some would say reckless) move from Cambridge to Exmoor, settling with our children in an old Devon longhouse in East Anstey. I had no idea where to move my bank account to, so I chose South Molton, about 18 miles away. I thought we would perhaps go there to market each week…In fact, we virtually never went there, but my account stayed put, long past our move away from the area, right until a few years ago, because banks have now stopped letting you change your branch. And then I received the grave news that it would now be switched to Barnstaple (it’s there still, I think), as the South Molton branch was to be closed. Robert and I found the evidence indeed when we visited in recent years. The plaque on the right hand side of the wall says ‘Midland Bank’, because that’s what HSBC was back then, before it took on the rather dubious title of ‘Hong Kong and Shanghai’!

Teignmouth

Teignmouth is glorious. When you first visit, you may think it’s only a standard seafront, pleasant enough, with promenade, gardens, and white 19th century hotels. However, a friend took me round the town and introduced me to the Back Beach, a picturesque muddle of boats, nets, huts, houses, pubs and workshops. And over the river, via the ferry, to Shaldon, which is a kind of cute Surrey village in miniature, with its own cricket green – once a genuine fishing hamlet, now quaintly unique. Teignmouth also has its bohemian arty streets (ie scruffy but charming) and a splendid Victorian railway station. What’s not to like?

Tuckenhaye

We’ve only visited this delightful corner of South Devon once, for a wedding anniversary break. Tuckenhay sits on a creek which in turn leads into the River Dart. There’s a whole world of boats and creeks to explore – if one had a boat. I have also been much influenced by Alice Oswald’s lengthy poem ‘Dart’ – the voices of the river as it flows from upland Dartmoor to Dartmouth – so it was a treat to meet a different and very beautiful stretch of the river.

Woodbury Common

Woodbury Common is our nearest bit of wild countryside, a patchwork of village commons that have survived as one stretch of open heathland. At one point after the war they were threatened with becoming a municipal rubbish dump – now they are protected, and carefully managed to preserve flora and fauna. We have often walked over different areas of them. It’s surprisingly easy to get lost! But every now and then, you maybe be able to orientate yourself by a glimpse of the sea. In the pictures below, you can see Bog Asphodel – I had to turn to the flower book to identify this one!

It’s from Woodbury that I’ll choose my final image – watching the sunset fall over the view from the ridge of the Common, towards the Exe Estuary. I took this while on a landscape photography course – some thirty of us lined up solemnly along the hill top, waiting for that moment when the sun starts to dip below the horizon. It seemed miraculous.

All photographs in this blog post are copyright Cherry Gilchrist, except where otherwise indicated