I plan to drop a few posts into Cherry’s Cache about my work as a writer, which has now spanned more than half a century. This first one is about what happens, or can happen, at the end of a book run. The next one will be about how I began writing for magazines – in this case the teenage magazine ‘Jackie’ in company with two schoolfriends. Then, if all goes according to plan (which a writer’s life never does) I’ll bring in early poetry outcomes. Hang on in there, all of them are more entertaining than they might sound!

The End of The Line

The background to this story is my interesting relationship with waste and recycling. In my teens, I haunted some of the very first charity clothes shops. There was a 1930s silk yarn crocheted top which I wore for years after I pounced on it in an early Oxfam shop. Then, as a college student, I volunteered eagerly to go to the town rubbish dump to pick up props for a play. I think we were after wooden beer barrels, and having made a deal on a couple of these, I was invited by the aged site caretaker to view the ‘special rubbish’ in his shed. (And yes, it was a genuine offer. I found some exciting items, as I recall.)

In the 1970s, when I was in my mid-twenties, I opened a first-wave vintage clothes shop in Cambridge, called ‘Tigerlily’. The word ‘vintage’ hadn’t been coined then, so we referred to our stock as ‘period clothing’. As I’ll be writing more about that in a later blog, it will suffice to say here that I used to drive up to the rag mills of Yorkshire to find treasures for my keen customers, hidden among the vast malodorous bales of old clothes.

The term ‘recycling’ was not in common use at the time either, but it was certainly practised in the rag mills. I was astonished and delighted to see how everything except suiting material could be sorted and put to good use. Headscarves were saved for export to Nigeria, crimplene dresses for British market stalls, gentleman’s waistcoats for Pakistan. Wool was to be re-spun, sorted by colour into vibrant piles on the decaying wooden floors of the old mill. And most important of all, as far as I was concerned, the ‘hippy stuff’ – Victorian petticoats, 1940s crepe dresses and the like – were put aside for people like me. But as for the suits and tweeds, they could only be pulped for cardboard.

After I finished my vintage enterprise, I thought I was done with the commercial face of recycling forever. But then, one day, it came my way again.

The article which follows was published in the ‘Author’ magazine in 2007. This journal of the Society of Authors covers many subjects, but I don’t think they’d ever had one on the problems of disposing old books before. Acceptance came the same morning! The fee helped to restore my costs, and soothe my wounded pride.

The End of the Line

‘That’ll be £7.36,’ he told me.

£7.36 for a thousand copies of my priceless book. Oh, and he wasn’t paying me – I was paying him, to get rid of them.

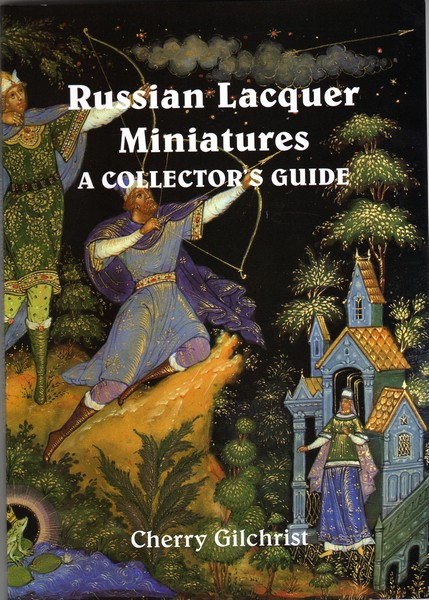

We were at the local tip in the city of Bath on a chilly autumn morning, amidst a cheerful crowd of householders disposing of their assorted rubbish. I’d been clearing out the attic before moving house, and had decided that I couldn’t take all these books with me. I’d had 4000 copies printed of my guide to Russian Lacquer Miniatures, which sold well enough through the gallery I had at the time. But would I ever sell the last 1800? I doubted it.

I also had several hundred remaindered books, other titles that I had bought up cheaply from my publishers, and some of their pages were looking distinctly yellow by now. So I ruminated on what I might do with them all.

Some of the books of which I had too many copies

My ex-brother-in-law, if one can have such a relation, worked for the Oxfam Books team. I emailed him: would he, on behalf of Oxfam, like copious quantities of books which I – ahem – couldn’t sell off? He replied, saying they would be glad to take my ‘back list’, and how many boxes did I have? Ah, back list! I knew there had to be a word for it, and back list sounds so much more reassuring, so professional and a part of the everyday ebb and flow of publishing. He arranged for the local van driver to come round and pick up a large pile.

But all the Oxfam bookshops in Britain, even if they each had an organised publicity campaign, couldn’t shift more than a thousand books on an obscure, if beautiful, Russian art form. Besides which, I still planned to sell some, and if my title swamped the market with 50p offers, or even a penny plus postage on eBay, what chance did I have to flog it at the usual £10? No, some would have to go to the dump; there was nothing else for it.

I cajoled my husband Robert into loading the books into the car; only authors who have had remaindered books will understand just how heavy the printed word weighs. This was all about the world of materiality, not of high ideas and fabulous prose. We drove to the refuse disposal site, as it is officially called, and tried to decide where to tip them. As you will doubtless know, each type of rubbish has its own marked bay. There are bays for cardboard and for paper, separate bins for bottles, clothes and shoes, a shed for electronics and TVs, and – oh yes – a skip for books. ‘Charities and schools will benefit from your donation’, it read reproachfully as we began hurling the book boxes into the Landfill Only bay. An attendant had already stopped us classifying them as paper, or as cardboard. And why wouldn’t we give them to the book skip, he asked?

‘Oh, copyright reasons,’ I told him loftily. ‘They must be pulped, you see.’

His supervisor loomed over us. ‘You can’t chuck those there,’ he said. ‘Those will take 200 years to decay. And what’s more, it’s commercial waste.’

‘No, no, it’s not!’ I said hastily. ‘They’re my books.’

‘They’re trade.’

‘They’re personal.’

‘Trade.’

‘Personal.’

‘So, do they form a part of earning your living?’

‘Yes,’ answered Robert, just as I said, ‘No.’

I was about to cite the Society of Authors survey on the low income of authors, and the plight of following one’s literary calling in this day and age. But my case was already lost.

‘You’ll have to go to the weighbridge,’ he said testily. ‘Ask for Glyn. You’ve got to pay for it, same as any builder’s rubble.’

I hope other authors reading this will be wincing at the prospect of our works being categorised along with bits of cement and broken bricks, with old posts and twisted metal railings, with bags of plaster and unspeakable filth from beneath the floor boards. The elegant sentences that you turn, dear fellow author, will become printed ink on the page, a page that is printed thousands of times, and will become ultimately, as far as worms, mother nature, and refuse supervisors are concerned, merely a chunk of matter that clogs up landfill and has no useful purpose to fulfil in the ongoing earthly cycle of regeneration.

We approached the weighbridge and the taciturn occupant of its hut.

‘Are you Glyn?’

The corpulent individual lounging against the doorway nodded.

‘What you got there?’

‘Books. My books!’ I said, hoping for a last minute reprieve.

‘Any good?’

‘Oh yes! A brilliant book. Would you like a copy?’

He thumbed it, wrinkling his nose. ‘Nah. Not interested.’

‘OK then, how much is it going to cost us to dump these?’

‘That depends on how much they weigh. You gotta weigh them in the car first.’

We were wondering where the weighing actually took place – Robert last remembered seeing a weighbridge by the M4, 12 miles away – when it dawned on us that we were already standing on the weighbridge itself, being counted along with the car and the books.

Then we were given permission to go back down to the bays.

The original supervisor had marched up to the weighbridge and back with us, to check our conduct. ‘Chuck it in with the cardboard,’ he said tersely.

My fabulous colour photographs, illustrating the book, were quantified as cardboard. But there was now a ray of hope for their evolutionary progress. At least they might turn up in a baked beans packing case somewhere, or perhaps be turned into boxes to house books of the future.

We threw our book boxes in, with satisfying thuds as they hit bottom, and returned to the office pay our dues. Then we realised that he was calculating the cost without us on the weighbridge, this time round.

‘Stop! We’re not on it!’ Robert called out.

‘Don’t make no difference.’

‘Oh yes it does,’ we said in one breath and leaped onto it to stand beside the car. It was bad enough to have to pay for the books, let alone be charged for our own weight as well.

Glyn announced the sum of money owing. £7.36. I had come without my purse, Robert had a fiver on him, and by scraping out the little film canisters where I keep change for parking, we paid our dues.

The receipt says, ‘Do call again.’ I don’t think I will – not unless I have to.

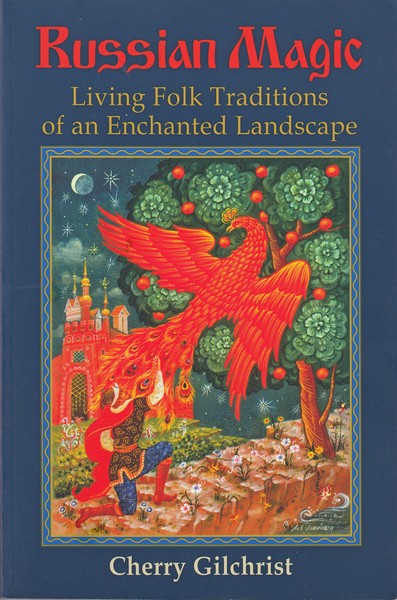

Editions of my other book on Russia, which thankfully I haven’t had to dispose of in the same way. Paperback and E-book versions.

You might also be interested in ‘The Russian Diaries’ and ‘The Cosmic Zero’

Owww – I feel your pain. Lots of pulped books end up as motorway sub-surface I believe. The M62 is supposedly built on Mills and Boon!

LikeLike

Oh the memories. I once took a smashed up shed to a council dump.

“You can’t drive that in here on a van! “

“ my van is used as a car!

“ doesn’t matter”

So we parked outside and walked the sections of the shed into the appropriate skip

“ It’s more than my jobs worth mate”

I got a dispensation to use my van as a car. Each time I went to the dump they checked the back for signs of commercial use. I couldnt wear a boiler suit or a flat cap. Or any tools. Or have the Sun on the dashboard

?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really amusing! Did you try having the Times crossword half completed lying on the dashboard??

LikeLike

I had a very tidy van I used as a car. My wife had the car. The back was carpeted. Just an Escort but it gave me an alternative ego. I played at being white Van man and was treated accordingly. RESPECT,!

LikeLike